Chapter 1

Anxiety about immigration is fuelling new forms of authoritarian populism and undermining faith in liberal democracy. A significant proportion of that anxiety can be explained by a general mistrust in the ability of governments to competently manage the system. Most people are pragmatic: they understand that nations must continue to be able to attract talent to grow and compete in the world—but they also want reassurance that the flow of new arrivals is properly planned for and managed, and that the laws are fairly enforced, with illegal migration tackled rather than tolerated. These are not unreasonable demands. The longer such demands appear to be unmet, the more space populism is given to thrive.

While the challenges facing individual countries are clearly unique, a common theme has emerged from our research: governments have lacked a coherent policy framework in responding to immigration. As a result, policies have often been driven by political short-termism, addressing the symptoms of public concern rather than the causes.

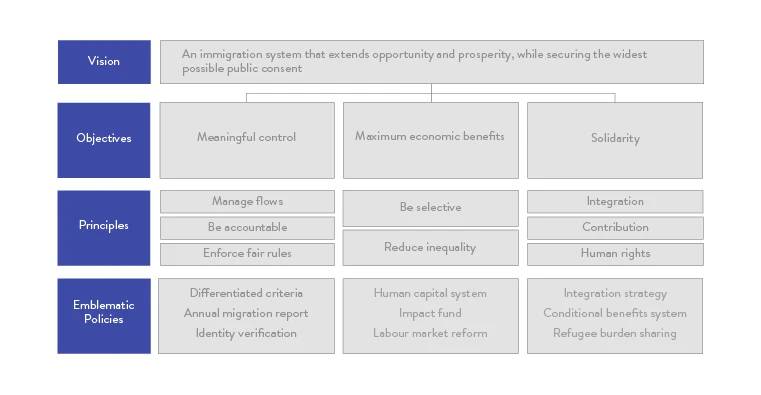

This paper is an attempt to address that. The policy recommendations contained in it are designed to meet the challenge of managing migration in the 21st century: a system of digital identity verification to tackle illegal migration, the adoption of human capital points-based systems, labour-market reform to reduce exploitation in the workplace, and a national strategy for social integration to drive greater social contact and encourage an inclusive citizenship. The intention is to give policymakers the tools to shift away from crisis-led policymaking towards a new progressive framework for the design and delivery of immigration policy (see figure 1).

A Progressive Framework for Immigration Policy

This framework defines three core objectives:

Meaningful control: Over the last decade, citizens have lost confidence in how governments have managed immigration, as a result of broken promises and a perceived lack of democratic accountability. An important objective is therefore to ensure that policymakers take steps to exercise meaningful control, keeping the pace and pattern of inflows manageable and tackling illegal migration, with proper accountability for how decisions are made.

Maximise economic benefits: Too often, immigration policy has been developed in isolation from broader economic policy. But they are inextricably linked. An important objective is therefore to ensure that the immigration system is aligned with a modern industrial strategy, plugging skills shortages in strategically important sectors of the economy. That means governments must be able to proactively attract the types of migrants that will most enhance economic productivity, rather than lumping all migration together into a single homogeneous bloc.

Solidarity: In a world of rapid population change, governments need to ensure immigration policy is designed to support, rather than undermine, social integration at home, providing greater clarity on the expectations placed on new arrivals and sufficient pathways to citizenship. At the same time, governments must avoid beggar-my-neighbour approaches to global migratory flows, including the movement of refugees, working in partnership with other governments and meeting their humanitarian commitments at the international level.

An immigration policy anchored in those objectives would have the following implications for the management of migratory flows.

ECONOMIC MIGRATION: A DIFFERENTIATED APPROACH

A balanced approach to managing economic migration would mean that for some types of migration, including high-value, high-skilled and migration for study, policy would generally be geared towards increasing numbers and maximising benefits to the receiving country. For others, such as low-skilled migration, entry would be demand-led, depending on the specific needs of the economy. Moreover, immigration policy would be integrated within a much broader set of reforms to the structure of the economy, including a modern industrial strategy to boost productivity and skills; increased enforcement of minimum-wage laws; and greater job security for workers. In the case of European Union (EU) migration, free movement would be respected but renegotiated, to enable an emergency brake during periods of exceptionally high inflows and pressures. [_]

ILLEGAL MIGRATION: A TOUGHER APPROACH

The framework set out in this paper requires governments to enforce a system of fair rules, which requires a comprehensive strategy to bear down on illegal migration. In particular, governments should make use of new technology to establish secure digital identities for all citizens, which would not only make it easier to identify illegal migration but also potentially give people greater access to their own personal data.

MIGRATION FOR FAMILY: CAREFULLY CONTROLLED

A balanced approach would recognise the importance of family reunification but ensure it is constrained by rules requiring spouses and extended family members to demonstrate that they can support themselves financially and integrate (for example, by speaking the language of the host country) before being allowed to enter.

ASYLUM AND REFUGEES: INTERNATIONAL ALIGNMENT

This framework requires liberal democracies to play a full part in responding to the refugee crisis. This should mean a comprehensive package of measures, including investment upstream, joint enforcement against traffickers and smugglers, strengthening refugees’ access to labour markets, and a proper system of burden sharing to ensure countries provide their share of resettlement places for refugees. Countries also need to invest in a more efficient asylum determination process to avoid backlogs.

In addition to managing the flows of new arrivals, immigration policy must manage their impact on arrival. This framework recommends the establishment of a genuinely responsive migration impact fund to support communities faced with rapid population change and pressures on public services, a national integration strategy, and a greater emphasis on contribution in the provision of welfare entitlements.

The framework set out in this paper seeks to balance principle with pragmatism. It aims to provide the basis of a political strategy that can secure long-lasting reform—reducing the scope for populists to use immigration as a tool to sow fear and division.

Chapter 2

With global movements of people at record highs and likely to continue for the foreseeable future, developing a credible policy agenda on immigration is a crucial task for liberal democracies. Accelerating immigration brings real challenges—for social integration, solidarity and fairness—that should matter to progressives. Moreover, it is increasingly clear that regaining the public’s trust on this issue is a precondition to electoral success.

THE GLOBAL CONTEXT: RAPIDLY RISING IMMIGRATION

The social, economic and political effects of migration are inextricably interwoven into the fabric of the West and its future. The flow of people across borders has been steadily increasing since 2011, now hitting record levels. Around 5 million people migrated permanently to countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2016, well above the previous peak observed in 2007, before the financial crash (see figure 2).[_]

Permanent Migration Flows to OECD Countries, 2007–2016

While migration for work—the majority of which is within the EU—remains the most common category of migration, a significant driver of the recent increase (50 per cent) has been the growth in humanitarian migration, linked to the conflict in Syria and ongoing instability in Libya and the Sahel.[_]

These challenges are unlikely to dissipate—indeed, the more likely scenario is that they will intensify. Technological and economic change will mean more people seeking to cross borders. Businesses and universities competing in a global marketplace will be increasingly hungry for the best international talent. Countries with ageing populations will depend on younger dynamic workers from abroad. Meanwhile, experts are already predicting that climate change and poverty will lead millions of people to seek a better life elsewhere. And the ongoing instability in Syria, Libya and the Sahel will continue to be at the heart of a refugee crisis in which millions have already been forced to flee their homes and seek refuge elsewhere.

While such immigration has brought significant economic and social benefits to receiving countries, the scale and the speed of these flows have also raised serious questions. There are social questions, relating to fears about the ability of some migrants to integrate within liberal democratic norms. There are economic questions about how certain economies have become so riven with skills shortages that they have become dependent on skills from abroad, rather than training at home. There are distributional questions arising from evidence that shows that low-skilled workers may have seen their wages fall as a result of rising migration. And there are questions about the international architecture required to deal with the sorts of unprecedented movements of people that have been seen as a result of the refugee crisis.

THE POLITICAL CONTEXT: A POLARISED DEBATE

There is barely a liberal democracy in existence today that has been untouched by political debate over immigration. It has uprooted governments, produced new parties and political alliances, and divided communities and generations. Hostility to immigration was a major factor in the recent electoral successes of right-wing populist parties across Europe, including the National Front in France, which secured 34 per cent of the popular vote having made it through to the second-round run-off in the 2017 presidential election, the Alternative for Germany, which captured 13 per cent of the popular vote in the 2017 German parliamentary election, and the Northern League and the Five Star Movement in Italy, which between them won more than 50 per cent of the popular vote in Italy’s 2018 general election.[_]

The prominence of immigration reflects its salience to voters. A poll conducted in 2017 found a majority of respondents in all European countries bar Finland said they were either “worried” or “very worried” about immigration (see figure 3).

Proportions of People Worried About Immigration, by Country

Why have policymakers, particularly those from established social democratic parties, struggled to articulate a credible policy agenda on immigration? Partly because they have felt conflicted: torn between a desire to open up opportunities for people from poor countries and the need to protect the poorest and most vulnerable groups in receiving countries; between the interests of individual migrants and the countries they leave behind; and between an understanding of migration’s positive economic impacts and fears that it may make communities less cohesive. [_]Confusion about how to weight these relative priorities has left policymakers divided and lacking a clear strategy for reform.

A second, related reason is that policymakers and politicians have often been frightened to engage with the issue, for fear of deepening divisions or pandering to irrational fears or prejudice. This has had two damaging consequences. The first is that there has been a vacuum at the centre of politics, meaning that the most prominent voices have been extreme ones. The second is that the genuine tensions and trade-offs that lie at the heart of migration policy have all too often been glossed over or ignored by mainstream politicians. Poor-quality policies are a reflection of the increasingly polarised nature of political debate.

This has to change. It is no longer enough to complain about the false promises of populists: progressives have an obligation to set out a position on immigration that can secure public consent backed up by credible policies.

When it comes to public opinion, there is less to fear than progressives might think. As this paper catalogues, when one looks at attitudinal data across Europe, many people have become more positive about the impact of immigration. They understand that their country needs certain categories of migrant workers, particularly the highly skilled. And they are not indifferent to the plight of refugees. But they believe—not unreasonably—that countries should exercise meaningful control over the flows of people coming in and that the system is fundamentally not well managed.

THE SCOPE OF THIS PAPER

This paper is an attempt to establish a progressive framework for immigration policy, using emblematic policies to highlight the potential for a different approach. Inevitably, the paper focuses on the role of the state in regulating the main categories of migration: work, study, family, humanitarian and illegal migration. But throughout, the paper makes the case for an immigration policy that extends beyond the border and is not developed in isolation but is connected with wider economic, social and cultural goals. Policies to restrict the supply of low-skilled migration make no sense in the absence of a strategy to reduce the number of low-paid and low-skilled jobs; similarly, attempts to stop illegal migrants from entering are doomed to fail unless the technology exists to know when people’s visas have expired.

This paper is not a comprehensive record of the evidence of the impact of migration (though a summary of the UK experience is provided in the final section). Nor are the policies included in this paper exhaustive. For example, it does not engage substantively with the question of EU free movement, which was covered extensively in 2017.[_] Similarly, while the paper touches on the issue of the European refugee crisis and the implications for international rules and governance, it is not the main focus here.[_]

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that this paper is written from a particular perspective, with a particular audience in mind—namely, policymakers and politicians working at the national level to manage migration. There are many people—on both left and right—who believe that the primary purpose of immigration policy should be to address global inequality by extending the opportunity to move across borders as widely as possible, and who feel uneasy about policies that implicitly prioritise the interests of citizens in receiving countries. This has sometimes been referred to as the ‘global citizen’ or universalist worldview: rejecting national allegiances in favour of a thinner, more individualistic view of society. It is important to outline why that view has been rejected here.

The first reason is that while global inequality is a real and urgent challenge, large-scale immigration from poor countries to rich ones is not the best way to rectify it. By definition, the people who can move across borders generally have more resources and more mobility than their poorer neighbours. Moreover, while immigration spreads opportunity (largely to the migrants concerned and their families), it also creates challenges—for the communities in which they settle and for the countries they leave behind, which lose some of their best-trained and most dynamic citizens. Quantifying the net effects of global migration is thus not straightforward.

The second reason is that the logic of the global citizen worldview on immigration—a world without borders and national loyalties—is based on a category error. It does not follow from a belief in human equality that people have equal obligations to everyone on the planet. Most people today accept the idea of human equality but remain pragmatic about how that is applied, believing that individuals have a hierarchy of obligations, starting with the family and rippling out via the nation-state to the rest of humanity. As such, there is no automatic conflict between a belief in global equality and support for the right of nations to manage their own borders. One can feel kinship with other human beings across the world while understanding the importance of nation-state borders.

Chapter 3

Immigration is already happening on an unprecedented scale. Moreover, as a result of long-term changes to the structure of the global economy and climate, rising immigration is likely to be a permanent part of our future. Recognising that structural context does not mean that governments are powerless to intervene, but it is essential to understand that managing migration requires addressing underlying causes, at home and abroad, and devising policy tools that reflect the complexity of the processes at play. Currently, however, governments have reacted to immigration with ad hoc initiatives, presenting no vision of what they want to achieve or coherent strategy to deliver it.

THE LIMITATIONS OF EXISTING POLICY APPROACHES

Across the established democracies of Europe and North America, there is democratic pressure to limit the inward flow of migrants and tighten controls. Yet what is often left unsaid is that there are competing priorities to which governments have to give credence. There are thus significant constraints on their capacity to determine who comes and who stays.

One constraint is that the nature of immigration means one government’s policy cannot be devised in isolation from that of other nations, or from broader international legal frameworks. For example, as a member of the EU’s Schengen Area, which allows for passport-free travel, and as a signatory to the European Convention for Human Rights, the German government has made choices that are, at least in theory, constrained by its obligations to uphold regional treaties and international humanitarian law.

Even governments that wish to severely restrict immigration have found that they cannot completely shut the door because of the economic price that the country would pay. In many countries, economic growth has brought not only demand for high-skilled workers for the knowledge economy but also an expansion in low-wage jobs. (There are some sectors of the UK economy, such as hospitality and social care, that would become virtually unviable were EU migrants to stop arriving in the UK.[_]) Similarly, governments must balance the effectiveness of border control with the reality of global travel and the enormous fiscal benefits of tourism. While governments must ensure they have the ability to screen new arrivals and keep out those without a legitimate right to reside, each minute of delay in passing through border control has an economic cost.

Trade-offs are the stuff of politics, but immigration policy has lacked a strategic policy framework that enables competing policy objectives to be weighted and the relative costs and benefits made transparent. This has had two important consequences.

Firstly, it has led to governments overpromising and underdelivering. Rather than sharing with the public the opportunities and constraints, the conflicting objectives and tough choices, successive governments have sought to reassure the public that migration is under control even while rising numbers have suggested it was not. Unsurprisingly, this has led to a deficit in public confidence.

Secondly, the lack of strategic policy has encouraged chronic short-termism, with governments tending to focus on policies that address symptoms rather than causes. For example, many governments worry about the political and social fallout from local workers having their wages and conditions undercut by low-skilled or illegal migrants, willing to work for less. Yet too often, governments have focused exclusively on migration policy, when the long-term solution lies in education, skills and labour-market laws.

These failures have undermined faith in the ability of democratic politics to manage immigration and created a vacuum, allowing populists to exploit people’s genuine anxieties. This urgently needs to change.

Case Study of Policy Failure: The UK’s Net Migration Target

In 2010, the UK Conservatives committed in their manifesto to cutting net migration to below 100,000. It was a short-termist tactical pledge designed to send a message that immigration could be lowered with the right level of political will. The commitment was initially popular but over the longer term proved politically toxic, not only for the Conservatives, but also for mainstream politics. It undermined trust in politicians’ ability to manage migration properly and arguably underpinned the outcome of the 2016 EU referendum.

The Conservative government was left in the absurd position of celebrating a rise in emigration and attempting to clamp down on foreign students, simply because they were the easiest category of migration to restrict. Meanwhile, delivering Brexit has become the primary mechanism for achieving control over the UK’s borders, even though migration from outside the EU has been higher than EU migration for decades.

A NEW POLICY FRAMEWORK

Meaningful international comparisons on immigration policy are difficult. The cold hard logic of geography dictates that the refugee crisis poses a much more direct challenge to countries on Europe’s external border, such as Greece and Italy, than to the UK. Similarly, the decisions Canada chooses to make about economic migration are shaped by its unique economic and demographic context—a large, underpopulated country seeking to grow its workforce—and are very different from the challenges faced by a country like the United States, whose political context is shaped by large numbers of undocumented workers and illegal flows, as a result of sharing a land border with lower-income Mexico.

Despite these differences, however, it is possible to identify common challenges facing most established democracies (such as the polarisation of public attitudes) and set out the foundations on which a progressive immigration policy should be built.

The purpose of immigration policy should be to extend opportunity and prosperity, while securing the broadest possible public consent (see figure 4). The following three sections flesh out these principles in greater detail.

A Progressive Framework for Immigration Policy

Chapter 4

A progressive immigration policy starts with the recognition that control matters. Even those who believe (as we do) that migration has generally been a force for good should accept that this does not mean that uncontrolled migration would be a good thing, even hypothetically. Just as the unfettered flow of capital can destabilise the economies of nations and the international financial system, so uncontrolled, unlimited migration would represent a threat to the social order on which liberal democratic nations depend.

How control is defined is fundamental. Often, it is used as a shorthand for restricting overall numbers. Yet how meaningful is a volume target to reduce overall migration if its biggest impact is to reduce precisely the categories of migration—high-skilled migrants and foreign students—that have highest levels of public support? Similarly, without a clear strategy for tackling high levels of illegal migration, it is unlikely that restricting economic migration will do much to secure the public’s confidence that the government has a grip on the system. Control needs to be meaningful, transparent and clearly articulated to reassure domestic populations.

Related to this, it is important that the policy debate reflects a more realistic sense of how much power government has to exercise control over immigration. Policy changes do have a real influence, and so does the way policy is implemented. However, other factors have an equally strong influence: global migration trends and flows, political factors elsewhere in the world, economic factors elsewhere and at home, and history. And yet a common feature of immigration debates is that people on all sides often suggest or imply that migration is determined solely by immigration policy.[_]

One example is migration from Eastern and Central Europe to the UK after 2004. The then Labour government’s decision not to impose transitional controls on countries that joined the EU in 2004 was a significant contributory factor in the rise in migration that followed. Yet the exclusive focus on that decision, while undoubtedly significant in the short term, has come at the expense of a wider discussion about the underlying drivers of European migration, many of which are unrelated to immigration policy, including the global role of the English language, the level of growth (both within the UK and in Europe) and the UK’s flexible labour market.

A more realistic sense of how much power governments have to control migration flows would help break the vicious cycle of politicians overpromising and underdelivering, a dynamic that has undermined public trust not only in immigration policy but also in governments across Europe. It would also enable the public to confront some of the real trade-offs involved in migration policy, such as border security, where there is invariably a set of choices involving spending (staff levels and technology), passenger convenience (including queuing times) and security (including the level of checks).[_] Populists prefer to ignore these trade-offs, choosing instead to imply that any problem at the borders is entirely down to incompetence or lack of political will.

Chapter 5

From these objectives flow a series of principles and emblematic policies. These are set out below.

MANAGING THE PACE OF CHANGE

It is not enough for progressives to set the rules and then take no view on the pace and pattern of migration flows that result. The ability of a government to set sensible limits over different categories of immigration is an important part of establishing public consent.

As outlined above, this must not be confused with a narrow obsession on overall inflows, which is counterproductive for two reasons. Firstly, overall inflows, while important, are not the only metric that matters here: the pace of change and level of population churn are arguably just as important. (Numerous studies have suggested that the level of population change in an area is a better predictor of populist voting patterns than the number of migrants in an area.[_]) Capturing the effects of short-term migration is thus likely to be as important as it is for longer-term migration.

Secondly, the ability and capacity of countries to manage migration flows successfully is contingent on a range of changeable factors—such as the nature and state of the economy, the demographic profile of the population, and the structure of public services—that make it problematic to focus on a single overall number. To put it another way, the capacity of countries to manage migration flows is affected by wider public policy. Change policy in certain ways, and the ‘right’ number for migration limits will go up or down.

Managing the pace of change is thus a more nuanced and practical principle when attempting to operationalise control over immigration.

Policy Recommendation

Introduce differentiated criteria for different types of migration. Setting a single, fixed target to limit overall immigration is unlikely to succeed. Nonetheless, it is important that governments clarify the aims of the system, enabling a better-informed dialogue with the public. An effective framework therefore requires a system of differentiated criteria for different types of immigration, rather than one crude overall number (see table 5).

Table 5: A Differentiated Approach to Managing Migration

Source: Adapted from “A fair deal on migration of the UK”, Institute for Public Policy Research, 2014

The levels of management in table 5 are indicative only—the criteria should not be fixed but should vary depending on labour-market requirements, recent immigration levels, democratic preferences and the global humanitarian situation. They would not operate as legal caps but instead function as objectives to guide policymaking, set public expectations and increase transparency.

Policy Recommendation

Reform EU free movement to establish a targeted emergency brake during periods of exceptionally high inflows. Countries that are members of the EU are in a different position from those outside the bloc, because membership involves adherence to the union’s system of free movement of people. Yet, free movement is not absolute. There is already considerable scope under existing EU rules to limit the scope of free movement, for example by operating a system of worker registration. Moreover, there are legal and political precedents that suggest more substantive reform to free-movement rules is plausible, such as allowing member states to enact an emergency brake to slow the pace of change during periods of exceptionally high inflows. The government should seek to pursue these options within the Brexit negotiations.

DEMOCRATIC ACCOUNTABILITY

The second principle follows from the centrality of immigration to modern politics. One of the most corrosive elements of the immigration debate in recent years has been a sense that immigration policy has been decided by elites (often behind closed doors), without any opportunity for the public to debate and/or have a say over decisions. Unlike other areas of policy (such as the national budget, which is agreed and debated at least annually), there are few established mechanisms for legislatures to debate immigration policy and for politicians to be held to account.

It has sometimes been argued that accepting that public opinion is a policy constraint is an abdication of responsibility, and that political leaders should try to lead public opinion in a more liberal direction, rather than pandering to ill-informed attitudes. This is a false choice. Political leadership on immigration is crucial, and populist approaches should be resisted, but this must always be tempered with realism about the ability to build a sustainable public consensus.

In fact, while public anxiety is real and significant, there is more reason to be optimistic about the public’s attitudes on immigration than often acknowledged. For example, European polling shows that the proportions of people in Britain, France and Germany who think immigration has benefited their country economically and socially have grown over the last decade. Moreover, most people remain positive about migrants who come to contribute through hard work and who seek to integrate.

Democratic accountability also provides a tool for resolving tensions and trade-offs. For example, how should policymakers weigh up the public’s apparent desire to cut low-skilled immigration against public reluctance to see shortages in key sectors of the economy (which rely heavily on low-skilled migrant labour)? These trade-offs should be rendered explicit, confronted and debated, rather than hidden away.

Policy Recommendation

Produce an annual migration report, delivered to the legislature, informed by meaningful data. Every year, the minister responsible for immigration policy should deliver a report to the legislature outlining progress in managing the immigration system, meeting the criteria outlined above and setting out announcements of any proposed changes planned over the forthcoming year. Legislators would have an opportunity to scrutinise the government’s performance and debate any new proposed policies. An independent, nonpartisan advisory body with equivalent composition and functions to the Congressional Budget Office in the United States could be given a formal role in publishing the impact of immigration on the country’s economy, on public services and on communities; the government’s progress on meeting its targets; and the likely effect of any proposed government reforms.[_]

ENFORCING FAIR RULES

A core element of exercising meaningful control is ensuring that immigration systems enforce the rules fairly and proportionately, including by reducing the level of illegal migration. There are both pragmatic and principled reasons why this is important. The pragmatic reason is that not doing so incurs a significant political cost: the perception that there are people in the country without permission reinforces concern that migration is out of control. Indeed, as the analysis in this paper later makes clear, a major driver of public anxiety about immigration appears to be linked to fears about illegal migration.

The principled reason is that the lack of legal status makes adults and children vulnerable to social exclusion and exploitation in and beyond the workplace.[_] Illegal migrants’ need to avoid detection and removal means they cannot easily exercise their fundamental human rights and/or the most basic access to public services. Moreover, failure to deal with illegal migration means that the state’s ability to curtail criminal activity and protect national security is potentially undermined. While there is no evidence that illegal migrants have any greater propensity to criminal activity than natives, large numbers of undocumented individuals raise the risk of terrorist-related activity going undetected.

Migration rules should be fair and consistent, but once decisions—whether about entry or removal—have been made, it is entirely legitimate for governments to enforce them, as long as it is done legally and humanely.

It is widely recognised that the weakest link in governments’ strategies to address illegal migration is the continuing capacity of unscrupulous employers to avoid compliance with employment standards, meaning illegal migrants are often paid below agreed minimum agreed levels and suffer poor working conditions. Countries’ visa and work-permit systems, including the labour-inspection regime, can and should be designed to minimise this, and wider regulatory systems should take greater account of the specific issues associated with migration. In particular, if employers are to know whether an individual is entitled to work and to check without discriminating on any grounds, all prospective employees must have reliable documentation—a secure system of identity verification appears critical.

Designing the right rules is only half the challenge: they must then be implemented. In the past, too little attention has been devoted to ensuring that the rules and policies are enforceable in practice and backed up with institutions that are resourced to work. It should be obvious that any government should care about competence. But this is particularly relevant in the context of the immigration debate: a significant part of the distrust felt by many members of the public—across many countries—is based on a perception that successive governments have managed migration poorly.

There are three enablers of good implementation. Firstly, effective migration policy needs to be based on accurate and timely data. For example, the UK’s migration statistics are based on a survey of people’s intentions at the point of arrival—they do not provide an up-to-date and comprehensive picture of who is entering and leaving the country. Similarly, it is very difficult to find up-to-date and reliable estimates of the numbers of illegal migrants in the country at any one time, with estimates of the UK population ranging from around 430,000 to 1 million.[_]

Secondly, the institutions tasked with delivering migration policy must be properly resourced. It is not reasonable to expect immigration authorities to identify and remove illegal migrants if they are understaffed.

Finally, many aspects of migration policy require successful cooperation at the international level. Individual governments need to engage effectively and strategically with international institutions to achieve their domestic objectives (as well as fulfil their obligations as responsible members of the international system). For example, without better European cooperation to police the continent’s external borders, efforts by individual countries to reduce illegal migration will be doomed to failure.

Policy Recommendation

Invest upstream to reduce illegal entry and modernise the border. There is no single magic bullet for reducing illegal migration—a comprehensive strategy is required. That starts with investment upstream to tackle illegal smuggling and trafficking networks. International institutions such as Frontex, the EU’s external-border agency, should be strengthened and expanded.

It requires investment in sophisticated visa regimes that screen for possible illegal migrants in countries that tend to produce high numbers of them, and modernisation of borders. Electronic visa waiver schemes, such as the US Electronic System for Travel Authorisation (ESTA) system, provide enhanced security by enabling countries to register non-visa nationals and freeing up frontline staff to focus on those arriving illegally. They also provide additional funding for border operations. Countries not covered by these schemes, such as the UK, should adopt them.

Policy Recommendation

Take advantage of new technologies to introduce citizen-centric digital identities for all citizens. Governments should implement a version of Estonia’s e-identity card system. This combines some aspects of a traditional physical identity card with the functionality to digitally authenticate users with government services and issue digital signatures on arbitrary documents.

To work and/or access benefits, individuals would be required to produce a claim that they have a legal right to reside, digitally signed by a recognised authority. To obtain such a claim, individuals would first need to establish their status with a recognised authority (likely to be a government department, other public-sector body or designated partner), by generating their own public or private key pair, and by providing their passport or equivalent documentation for verification. In return, they would receive one or more digitally signed claims that would be unique to them and credible when shared with third parties.

Case Study: Estonia’s e-Identity System

Estonia has one of the most highly developed national ID card systems in the world. Technically, it is a mandatory national card with a chip that carries embedded files, and using 2,048-bit public key encryption, it can function as definitive proof of ID in an electronic environment. Functionally, the ID card provides digital access to all of Estonia’s secure e-services, speeding up verification and making daily tasks faster and more comfortable. This includes accessing healthcare, setting up banking accounts, signing documents or obtaining medical prescriptions. E-citizens can provide digital signatures using their ID card or on their mobile phone.

Digital authentication (including the use of secure data sharing technologies, such as blockchain) addresses two of the major problems with traditional identity cards: It avoids the need for a centralised database linking all of the different functions for which a person has used his or her identify card (protecting privacy vis-à-vis the state and avoiding a honeypot for hackers). And it avoids oversharing by limiting assertions to the need-to-know information for a particular context.

A digital approach would not only make it easier to track and identify illegal migration; it could also be used to empower citizens. For example, in Estonia, citizens can use their digital identity card (or mobile phone) to book doctor’s appointments and sign documents. Citizens in Estonia also have more control over their personal data. They have a unique identifier that allows them to access their health records and review requests by third parties to access their data.

Chapter 6

A core objective of immigration policy is that it should be designed with the objective of increasing the benefits of migration and reducing the costs, for the country as a whole.

Underlying this is the question of how the economic benefits should be measured. Historically, governments have typically measured the economic benefits in terms of the contribution migration makes to gross domestic product (GDP). Some economists have since shifted away from this metric on the grounds that it is overly crude and misleading. For example, migration can increase GDP per capita either by increasing the employment rate or by increasing productivity—but in either case, benefits may theoretically still accrue primarily to migrants themselves, without creating advantages for the previously resident population.[_] As a result, some economists now argue that migration policy should be tested according to whether the resulting scale or type of migration increases GDP per capita for society as a whole.[_]

Ultimately, immigration policy should be viewed as one pillar of a broader economic strategy. Immigration should support an economy in which firms are incentivised to create high-quality jobs and invest in training their local workforce, rather than being pushed into a short-term, low-skill approach.

Chapter 7

SELECTIVITY

One of the implications of an economically focused approach to migration is the principle of selectivity, whereby governments aim to control the characteristics of migrants admitted for long-term stays and/or the type of employment they are entitled to take up. A progressive approach should involve policies designed to attract categories of economic immigration that contribute to the economy of the receiving country while ensuring there is enough flexibility to be able to bring in lower-skilled migration to fill specific skill shortages in priority sectors of the economy.

Broadly speaking, there are three key models for achieving selectivity.

Human capital points-based systems, drawing on examples from Australia and Canada. In such systems, points are weighted to select skills that match existing and projected shortages and are designed to prioritise those who demonstrate the most potential to settle in the receiving country. Once selected, migrants are not tied to any particular job (though in the Australian system, there is a two-year residency requirement). There are challenges to implementing such a scheme, given the intensive process of selection and screening involved, although it is also relatively easy to enforce, because there is no requirement to enforce restrictions, for example in access to employment or services.

Employer-led schemes, with examples from the UK, Switzerland and the EU Blue Card. In such systems, employers with sponsor status may recruit foreign nationals to fill vacancies if a number of conditions are met, including specified salary and skills thresholds and a resident labour-market test. Such schemes almost always involve setting a nationally (or regionally) agreed quota. While these schemes provide good flexibility for employers, they score less well in terms of meeting longer-term economic needs, because recruitment responds to immediate employer needs rather than to projected shortages.

Occupational shortage lists, drawing on examples from the UK, New Zealand and Spain. Such systems imply relaxing the criteria for firms to recruit foreign labour in occupations facing shortages. As with employer-led schemes, this involves setting a nationally agreed quota. In contrast to employer-led schemes, this approach scores well in terms of meeting both immediate and projected labour shortages, because government inevitably has a greater role in planning and monitoring.

Different approaches can also be combined. For example, the current UK points-based system for non-EU migration includes an element of all three of the models described above, though most migration arrives via the second and third.

On balance, human capital points-based systems appear most aligned to the needs of a modern economy. Unlike employer-led schemes (which tend to be bureaucratic for businesses) and shortage occupation lists (which involve significant central planning), human capital points-based systems are generally more flexible. They are thus more likely to capture the dynamic benefits from high-value and high-skilled migration than are demand-led approaches.

Finally, there is the question of whether economic migration is encouraged to be permanent, with clear pathways to settlement offered, or whether temporary guest-worker schemes are preferred. The most infamous such scheme was implemented in Germany in the decades following the Second World War. The Gastarbeiter (guest worker) policy, focused on Turkish migrants, ran from the late 1950s to the early 1970s. The general assessment of this scheme is that it was not a success. It was controversial from the points of view of fairness and integration, and ineffective in its stated aim, with large numbers of supposedly temporary migrants staying permanently. In Germany, the Gastarbeiter policy led to the popular slogan “There is nothing more permanent than temporary workers”, as millions of Turkish guest workers and their relatives ended up settling by default.[_]

Case Study: Canada’s Merit-Based Immigration System

Canada has put the principle of merit at the heart of its immigration system, with immigrants selected based on their human capital rather than simply their country of origin. The purpose of the system is relatively simple: to bring in immigrants, regardless of where they were born, with vetted qualities that will increase their chances of successfully integrating into the Canadian economy.

Under the merit-based system, candidates receive points according to their level of education, their ability to speak one or both of the country’s official languages, their work experience, their age, whether they have a job offer and what immigration officials call adaptability, which refers to whether they come with family or have family in the country. More recently, following the election of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the criteria were reformed, with the number of points awarded for a job offer reduced and points added for candidates who had graduated as foreign students from a Canadian university. There is also a regional component—the provinces can add separate points systems based on local jobs markets. For example, Alberta is seeking to recruit food and beverage processors.

The merit-based system has a number of benefits. Studies have shown that economic immigrants arriving with more education and language skills land higher-paying jobs and tend to give birth to children who do better at school. The system has also been praised for creating a positive feedback loop, whereby the public is more willing to buy into immigration because people are confident that it is managed and that those coming in have skills that Canada needs. However, Canada’s distinctive geographical and political context makes comparisons with other countries difficult. The merit-based system needs to be seen in the context of attempts to increase migration, rather than reduce it (Canada aims to increase inward flows by 0.85 per cent of its population—around 300,000—every year).

Policy Recommendation

Increase the flow of foreign students. Migration for study is a rare breed in policy terms, in that it represents a win-win, raising revenue to support the funding of universities while facilitating cultural enrichment through the exchange of ideas and learning. Governments should make it an explicit goal to increase the flow of students across borders. As a first step, students should be removed entirely from systems designed to regulate economic migration—and instead treated as an entirely different category and managed separately.

Policy Recommendation

Adopt a version of Canada’s human capital points-based system, to attract high-value and high-skilled migration. The evidence is clear: high-value and high-skilled migration brings enormous economic benefits to receiving countries. To attract such migration, countries should adopt a version of Canada’s human capital points-based system, which has the merit of greater flexibility than systems based on employer demand or shortage occupation lists (such as in the UK) and enables the dynamic effects of migration to be captured. Such systems are flexible enough to be tailored to individual countries’ needs, for example giving particular credit to graduates or skills in strategically important occupations or sectors.

Policy Recommendation

Control low-skilled migration, primarily by lowering demand. The economic merits of low-skilled migration are less clear-cut than for other categories of migration and should therefore be subject to greater control. Yet policymakers must understand the direction of causation. While immigration affects the economy in a wide range of often complex ways, the way the economy works also affects patterns of migration. For example, the current structure of the UK and US economies—open, flexible, lightly regulated—has as strong an effect on migration patterns and levels as does migration on the structure of these economies. Thus concerns about low-skilled immigration pushing down wages and conditions should be addressed primarily through the development of a modern industrial strategy, which reduces the number of low-paid, low-skilled jobs, and through changes in skills and training policy—lowering demand at source.

Even allowing for the above, it is important to be realistic about the continuing importance of low-skilled migration to modern economies. The truth is that governments will always need to address labour shortages in lower and unskilled occupations. This can be achieved via points-based systems, seasonal-worker schemes or, in the case of EU countries, freedom of movement.

Policy Recommendation

Incentivise economic migrants to settle. A critical success factor in the management of economic migration is that such migrants are offered clear pathways to permanent settlement. While this might lead to some political controversy, the virtue is that by doing so, countries can invest in recruiting those who are most likely to integrate and settle. And through offering generous rights, they ensure immigrants can contribute positively to the host society and economy. This is a far more foresighted approach to recruitment than a focus on addressing labour-market gaps through short-term visas, which risks creating a two-tier workforce, with differing rights and obligations and an increasing level of population churn.

REDUCE INEQUALITY

Alongside the overall economic impact, policymakers need to be alive to distributional concerns. The extent to which recent migration might have reinforced wider trends towards income inequality, for example by placing downward pressure on wages for the lowest paid, should be a factor in policymakers’ decision-making, even if those effects are small and ultimately outweighed by other factors.

Migration policy is unlikely to ever form a significant element of a wider policy package aimed at reducing inequality. But a progressive migration policy must try to ensure that migration does not add to inequality and, if possible, coheres with a broader approach that attempts to reduce it. These effects are inevitably complex to measure. For example, a migrant worker earning the minimum wage in the receiving country may be better off than at home, in absolute terms, but may find him- or herself at the very bottom of the economic and social heap, unable to engage with the rest of society, and therefore less happy as a result.[_]

Beyond a general concern with inequality, a progressive migration policy should also be designed to avoid any negative effects that migration might have on the poorest and most vulnerable groups or communities, or at least include policies designed to mitigate their impact. This might include pressure on rents in areas where housing is in short supply or the more generalised impact of rapid churn in communities already struggling with multiple problems.

Policy Recommendation

Reform the labour market to reduce a race to the bottom in wages and working conditions. A key element of this framework involves reform to the domestic labour market, to reduce the worst cases of undercutting of wages and conditions (lowering standards for everyone else), while lowering demand for low-skilled migration over the longer term. In practical terms, this should include:

properly resourced labour-market inspection to identify exploitation and abuse, with criminal prosecutions and heavy fines for employers who break the law;

tougher enforcement against illegal undercutting of wages, with a mix of civil penalties and prosecutions; and

regulating against the practice of recruitment agencies directly hiring directly from abroad, making it impossible for local workers to compete for jobs.

Case Study: The Role of Labour-Market Regulation in Restricting Low-Skilled Immigration

With a population of just under 9 million, Sweden is the biggest Scandinavian country, with one of the world’s most advanced social welfare states and a heavily regulated labour market. In particular, the continuing strict requirement that all workers be employed at collectively agreed wages—an enduring key feature of the Swedish model—is thought by some economists to have acted as a strong deterrent for employing large numbers of migrants.

Martin Ruhs, a labour-market economist from Oxford University, argues that Sweden’s high level of labour market regulation helps explain why Sweden saw a relatively small number of Eastern European migrants enter and take up employment (under 50,000 in total between 2005 and 2010), despite being one of only three countries (along with the UK and Ireland) not to impose transitional restrictions on the employment of workers from eight Central and Eastern European countries following EU enlargement in 2004. By contrast, the UK and Ireland—both countries with more flexible labour markets—experienced significantly greater inflows of workers from Central and Eastern Europe after 2004. (It is of course possible that similar numbers would have arrived illegally had the UK and Ireland not imposed transitional restrictions.)

The Swedish experience offers a key insight into debates about economic immigration. Low-skilled immigration and demand for migrant labour is in practice influenced by a wide range of public policies (labour-market regulation, training policies and so on) that go beyond migrant-worker admission policies.

Policy Recommendation

Introduce a beefed-up migration impact fund to help local communities manage the impact of rapid population change. The costs of immigration are not spread evenly among pre-existing populations, and some communities have experienced very high levels of population change, which has generated pressure on local services, including schools, hospitals and housing. These areas should be granted additional resources by central government to expand and improve their services to ensure that they can cope with the relatively high inflow of migrants.

To be effective, the funding would need to be both substantial and flexible, with the ability to allocate resources in real time, rather than on a two-year rolling timetable. This could be paid for partly from visa fees. There are precedents for such a model, albeit on a smaller scale. In the UK, the last Labour government established a Migration Impact Fund in 2009 worth £35 million a year, which distributed resources to local authorities. The fund was subsequently abolished by the Conservative-led coalition government in 2010.

Chapter 8

The third pillar of the framework proposed in this paper is concerned with the social dimension of immigration. As analysis of public opinion makes clear, many of those who are most concerned about immigration explain this concern by saying that immigration is threatening the national way of life or that social integration is being weakened, particularly as a result of rising migration from Muslim-majority countries. Such concerns need to be engaged with, rather than dismissed, because they are central to the question of how governments build solidarity.

There are different dimensions to this question. The first relates to the effects of immigration on social integration. Progressive policymakers ought to be especially sensitive to any evidence that immigration may have undermined people’s willingness to buy into a system of shared public goods funded by taxation. Similarly, policymakers must be attuned to the extent to which certain patterns of migration are associated with higher levels of social segregation—and be prepared to use all the levers at their disposal in addressing it.

A second dimension relates to the expectations and obligations placed on migrants who settle in receiving countries. As analysis of public opinion illustrates, there are very high levels of public support for migrants who contribute economically, socially and culturally. Governments need to ensure that the provision of welfare and other public services nourishes, rather than undermines, the principle of contribution.

A final issue is whether immigration policy should consider solidarity in its broadest, international sense, by encompassing impacts on those forced to flee because of persecution or civil war and the countries they leave behind, as well as in receiving countries. As the president of the International Rescue Committee, David Miliband, has argued eloquently, the question of how the West deals with the current refugee crisis (with the biggest peacetime movement of people since the Second World War) is as much about Western values and identity as it is about those of the refugees.[_] At the very least, it seems logical that a policy that recognises the benefits of offering migration opportunities to individuals in developing countries should be coherent with a development policy that seeks to improve the lives of the majority who remain.

Chapter 9

SOCIAL INTEGRATION

The last two years have demonstrated that countries across the developed world are more anxious and fragmented than previously understood. Countries are increasingly split by place, by generation and by social class, casting new light on more long-standing divisions. With record levels of immigration, it is more important than ever that migration policy includes a robust commitment to promote social integration.

Integration is a nebulous concept that has been defined in different ways. For the purposes of this paper, an integrated society is defined as one in which all members of that society feel that they have a strong mutual bond with, and mutual regard for, every other member of that society. It is not to be confused with forced assimilation, which requires migrants to leave their identity at the border and fit in. Integration does not rule out individual or group differences but implies that the expression of that difference should not come at the expense of shared values and mutual obligations. The aim is to increase the amount of interaction among different groups and strengthen a sense of shared identity, locally and nationally.

A national policy to prescribe how people live together will always be controversial. Yet in a world of mass migration, it is not sustainable for policymakers to take no view on it.

Policy Recommendation

Adopt a national integration strategy, including key commitments on language, hate crime and social contact. Governments should adopt integration strategies that:

ensure sufficient language provision is available to enable migrants to speak the language of the host country and communicate effectively (part funded by visa fees), with clear expectations that migrants make use of such provision;

take action to promote shared citizenship, while tackling prejudice and hate crime, through education;

invest in institutions and activities that promote greater social contact, such as citizenship programmes for teenagers and the teaching of shared values; and

prevent a shift towards social segregation in schools, through reform of admissions policies.

Case Study: Merkel’s Integration Summits

Germany has the second-highest share of migrants in any population worldwide after the United States. In the mid 2000s, the issue of migrants’ integration into German society rose up the political agenda, in particular due to the lack of German spoken by large numbers of migrant families and disproportionately high levels of unemployment.

In response to these concerns, German Chancellor Angela Merkel invited representatives from federal states, local authorities, industry associations, trade unions, churches and religious leaders to take part in the country’s first ever integration summit in 2006. This was in explicit recognition of the fact that in the words of German Commissioner for Migration, Refugees and Integration Maria Böhmer, “the government alone cannot fulfil the integrative tasks, which are a responsibility of our entire society. Integration will only be successful, when everyone—immigrants and native Germans—assume practical and concrete responsibility. This is the only way to develop a lasting climate, which encourages migrants to consider themselves as natural parts of our society.”

At the summit, it was agreed to develop the country’s first National Integration Plan, to achieve the following national objectives: promote the German language from the start; ensure good education and training; improve employment opportunities; improve the lives and situations of women and girls; and strengthen integration through civic commitment and equal participation.

A year later, in 2007, a second integration summit was held at which 400 actions and commitments were agreed by the federal government, NGOs and migrants’ rights organisations. The most significant were:

a significant extension of job-related language training;

a strengthening of integration courses;

a federal network of education sponsors to support children and youths from migrant families in school and training courses;

the development of general language training for children in day-care centres;

an expansion of apprenticeships targeted at migrant youths; and

a ‘diversity charter’ business initiative to promote the recruitment of migrant employees.

An integration summit has been held every year since.

CONTRIBUTION

The response by progressive politicians to public concern about migrants claiming benefits has often been to downplay them, for example by pointing out that migrants’ access to and take-up of benefits tends to be relatively low, and that the volume of abuse through so-called benefit tourism is tiny. Of course, it is right to challenge false assertions by populists that migrants act as a drain on countries’ resources. But in seeking to challenge misinformation, a broader truth is often missed: the concerns people have are not fundamentally about the volume of abuse, but about whether the rules themselves are fair.

At the heart of this issue is the perception that contribution—the idea that what people receive reflects what they put in—has been steadily eroded from the provision of welfare entitlements. (It is noteworthy that these issues extend beyond migrants: similar arguments have been made about ‘welfare queens’ in the United States and benefit scroungers in the UK.) To tackle the perception of unfairness, governments must therefore do more than design measures aimed specifically at migrants; they must introduce a more explicit contributory element into the welfare system.

Taking seriously the principle of contribution would imply a tightening of policy in two particular areas: the eligibility criteria that regulate entries of new arrivals (particularly those seeking to migrate for family reasons) and the rules that govern access to benefit entitlements and public services.

Policy Recommendation

Ensure that migration for family reasons supports economic and social integration. Policymakers should recognise the importance of family life. In the context of encouraging settlement and citizenship, they should not seek to separate migrants from their close family members arbitrarily, particularly with respect to asylum seekers and refugees. However, it is also true that family migration routes can be used to get around other forms of immigration control and can, in certain instances, contribute to social segregation, while acting as a drain on state resources. A modest set of obligations should be placed on the sponsors of family migrants, consisting of:

salary thresholds, set at a level that reflects the individual’s ability to work and participate. This should be increased for each additional child, reflecting the costs to the state of providing childcare, education and welfare entitlements; and

a requirement that partners must be able to speak the language to a reasonably high level.

Policy Recommendation

Make the contributory principle within welfare explicit. For most migrants with limited leave to remain, access to non-contributory benefits is already severely restricted under variations of the ‘no recourse to public funds’ rule. Rather than further tightening the rules surrounding migrants’ ability to claim, governments should introduce broader reform of the welfare system to make the contributory principle more explicit, so that for all who use it—migrant and natives alike—there is a clear link between what people put in and what they can take out.

HUMANITARIAN PROTECTION

How the world responds to the refugee crisis that began in 2015 is a question that straddles several big areas of policy, including immigration, international development and globalisation.

Attempting to fold this question into a policy framework built around securing consent for a system of balanced migration does not necessarily do the issue justice. However, to ignore asylum and refugees completely would be equally wrong, as it remains a live element in the broader debate about immigration, particularly in Southern and Central Europe.

Our position on asylum and refugees is framed by the following three assumptions.

The 1951 UN Refugee Convention remains the bedrock of international cooperation, and all civilised nations must seek to play their part in upholding its spirit.

Many countries, including the UK and the United States, have a proud tradition of providing a place of sanctuary for refugees. This tradition needs to be cherished, rather than taken for granted.

A combination of civil conflict, weak states and climate change means that the types of flows witnessed in recent years are only likely to grow.

It is clear that asylum processes have been put under considerable strain by recent patterns of international migratory movement, following conflict and political instability, particularly in Syria. This has often made it difficult for receiving countries to separate out genuine refugees from people who are abusing, or should not be using, the asylum route. In particular, countries on the edge of the EU, such as Italy and Greece, which evidently lack the infrastructure to cope with sudden surges in asylum applications, have borne a disproportionate share of the burden, leading to growing backlogs of cases.

The 2015 crisis exposed the weakness of intrastate asylum and refugee cooperation. Resettlement schemes remain ad hoc, reinforced neither by long-term international agreements nor by regular UN processes. Family reunification, which should hold a central place in asylum and refugee policy, is underused or, worse, restricted. Refugees integrate more quickly with their closest family members—spouses and children—when alongside them, yet states reinforce isolation and fragment families across nation-states.

More broadly, the burden of resettling refugees is not shared equally (see figure 6). Globally, the top ten refugee-hosting countries account for only 2.5 per cent of world income. By contrast, Europe and the United States, which together represent 45 per cent of world income, take in 11 per cent and 1 per cent of the world’s refugees respectively.[_] There are notable exceptions. In 2015 Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel made the courageous commitment to resettle 1 million refugees. Other countries, such as the UK and Norway, have accepted far fewer refugees, arguing that their resources are better spent on improving conditions in refugee camps in neighbouring countries.

Numbers of Syrian Refugees in Neighbouring and European Countries

The failure to coordinate internationally has created resentment across Europe, which is undermining faith in democracy and fuelling populism. In Germany, unhappiness over Merkel’s decision (exacerbated by a series of terrorist attacks involving undocumented migrants) is widely thought to have been a factor in the far-right Alternative for Germany winning 12 per cent of the popular vote in the 2017 German federal election, denying Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) a working majority.[_] US President Donald Trump has used recent terrorist attacks in the United States and mainland Europe as an excuse to introduce a ban on refugees from Muslim-majority countries.

The central policy challenge is thus twofold. Firstly, at the national level, it is crucial to construct a fair and efficient system that is capable of processing asylum claims in a way that ensures that well-founded cases are granted refugee status and vexatious claims are rejected and claimants returned to their countries of origin when it is safe to do so. Secondly, it is essential to make the European and international legal and policy frameworks that govern support for refugees fairer and more effective.

Policy Recommendation

Make a concerted effort to reform the legal and policy frameworks governing support for refugees and asylum. A commitment to solidarity and social justice must mean an international framework of rules that binds countries to a system of humanitarian protection and resettlement, so that the burden of offering support to refugees is shared equally across countries, rather than being borne by a small proportion of countries. This should be based on a commitment to:

use development spending to invest upstream in establishing safe places for displaced people in regions of origin and ensuring refugees have rights and freedom to live;

increase international coordination at the European level to strengthen enforcement against human traffickers and smugglers, developing the new entry/exit system on Europe’s external borders;

push for reform of the EU’s Dublin Regulation on asylum seekers, bolstering family reunification rights and moving towards a system of shared quotas, to rebalance the burden among receiving countries (or allow for an offsetting of that burden in other ways, for example financial compensation). The gap between countries of similar economic weight, such as Germany and the UK, is politically unsustainable and must be narrowed;

improve the integration of refugees, by giving them access to labour markets;

investment in, and reform of, the asylum determination system to improve the quality of initial decisions (including through training of case workers) and speed up the processing of asylum claims. Failed asylum seekers should be swiftly returned, with a greater focus on voluntary return and support for people being returned, rather than forced removals; and

introduce statutory time limits for the detention of asylum seekers.

Chapter 10

It is often assumed that people’s views about immigration are binary, with the public split between those in favour and those who are hostile. In fact, a more detailed examination of public opinion suggests a more nuanced understanding of attitudes, providing support for the core principles that underpin the policy framework proposed in this paper.

THE SPECTRUM OF OPINION

Positive About Immigrants, Negative About Government Handling

Most people reject the extremes of both sides of the immigration debate: they are neither in favour of pulling up the drawbridge, nor do they wish to see open borders. They are ‘balancers’—people who see both the pressures and gains of immigration.[_]

Related to this, people tend to think differently about immigrants as people and about immigration as an issue. When they think of immigrants as individuals, they often see the way immigrants enhance their neighbourhoods and public services and how they work hard. Cross-country surveys suggest people’s views about the impact of immigrants have improved over time. For example, a survey that asked respondents in the UK, France and Germany whether they agreed with the statement that “immigrants are generally bad for the country” found that fewer people agreed with that statement in 2016 than was the case in 2010 (see figure 7).

But when people think of immigration as an issue, they link to government failure and growing economic insecurity.[_] This would explain the apparent contradiction in cross-country attitudinal data, with the public growing increasingly distrustful of their government’s handling of migration policy while simultaneously more positive about its impacts.

Support for the Statement That “Immigrants Are Generally Bad for the Country”, 2008–2016

Immigration Not a Homogeneous Bloc

There is evidence that the public differentiates between types of migration. A 2016 UK survey asked people about their attitudes to different categories of immigration, broken down by the main categories (see figure 8). A majority of people supported increasing the level of high-skilled immigration (46 per cent), while only 12 per cent said they would want to see it reduced. Similarly, while 54 per cent responded that they would be in favour of keeping migration for study at the same level, only 22 per cent said they would like to see it reduced.[_] By contrast, the public tends to be more sceptical about low-skilled immigration, immigration for family reasons and asylum seeking.

UK Public Opinion on How Immigration Levels Should Change, by Type of Migrant

DRIVERS OF PUBLIC CONCERN

Competence and Good Management

The public tends to put a high premium on governments’ ability to competently manage the system and to enforce the rules. Unfortunately, their perception is almost universally negative in this respect, with most people’s opinions of government performance poor and getting worse.

The Transatlantic Trends Survey published in 2014 found that large majorities in the United States and the EU disapproved of their governments’ handling of immigration (see figure 9). Overall, 60 per cent of EU citizens said they disapproved, as did 71 per cent of Americans. Disapproval in Europe was most pronounced in Spain (77 per cent), Greece (75 per cent), the UK (73 per cent), Italy and France (both 64 per cent).

Approval Rates of Governments’ Handling of Immigration

Managing Illegal Migration and Improving Integration

According to the Transatlantic Trends Surveys, respondents have remained consistently more worried about illegal immigration than about legal migration (see figure 10). In 2013, more than 75 per cent of people in the UK and Italy worried about illegal immigration, compared with around 25–35 per cent worried about legal immigration. Similarly, more than two-thirds of people in Spain, Germany and France said they were worried about illegal immigration.

Levels of Concern About Legal and Illegal Immigration

Large numbers of people also worry about immigrants’ lack of integration, particularly with regard to migrants from Muslim-majority countries. A 2016 survey by the Pew Research Center asked respondents whether they thought Muslims wanted to adopt the host country’s customs and way of life or wanted to be distinct from the rest of society. The findings revealed that large majorities across Europe thought that Muslims wanted to be distinct (see figure 11).

Perceptions About Muslims’ Desires to Integrate

WHAT THE PUBLIC WANTS

Cross-country comparisons of public priorities are always difficult, but it is possible to draw four broad conclusions from the data.

Firstly, people want the government to deliver meaningful control. This means different things in different countries, but the data suggests it includes measures to manage the pace of change, enforce the rules, deport illegal migrants and ensure the public are given a chance to influence policy.

Secondly, people want governments to take a balanced approach. They want to be able to continue to attract the top talent from around the world, while doing more to limit low-skilled migration, asylum seeking and illegal migration. There is very high support for more high-skilled migration and migration for study, and people are generally supportive of governments doing more to provide humanitarian protection to refugees.

Thirdly, it is clear that the public wants governments to do more to encourage economic and social integration between newcomers and settled residents, and to ensure migrants contribute, though there are some regional differences. North Americans prioritise economic integration, whereas the Dutch put comparatively stronger emphasis on cultural adaptation. In terms of policy, there is very strong support for language classes (85 per cent in Europe, 88 per cent in the United States), banning discrimination in the labour market (81 per cent and 72 per cent) and the teaching of mutual respect in schools (94 per cent and 88 per cent).

There is variation, however, on the relative weight given to the different options (see figure 12). Germans tend to value language by a large margin: 44 per cent say the ability to speak the national language is the most important precondition for obtaining citizenship, compared with 26 per cent of UK respondents. Italians are the most focused on respecting national institutions and laws (75 per cent), compared with the European average of 52 per cent.

Most Important Criteria for Citizenship Acquisition

Fourthly, there is support for greater burden sharing at the international level, with respect to refugees: 80 per cent of people polled by the Transatlantic Survey in 2011 agreed that responsibility should be shared by all countries in the EU, rather than borne solely by the country in which migrants first arrive. Lowest support was expressed in the UK (68 per cent), and highest support in Italy (88 per cent), followed by Spain (85 per cent). In those countries closest to the migrants’ source states and bearing the brunt of flows, the public expressed the greatest interest in receiving support from other countries in the region.

Chapter 11