Chapter 1

As a society, we need to better understand what drives violence on our streets and, just as importantly, what government and the community ought to be doing to prevent it. The focus of this report – children on the cusp of, or already involved in, violence – is therefore vital.

We already know that there are millions of vulnerable children in England. Almost 400,000 children are identified by local authorities as in need and requiring support, while a further 80,000 are looked after, away from their families, by a local authority. Over 50,000 children aren’t getting any kind of education and over 400,000 children received fixed-period exclusions in 2018/2019. Nearly 30,000 children are caught up in violent gangs, with a further 300,000 children aged 10–17 saying they know someone they would define as a street gang member.

A minority goes on to commit violent acts – but it is a minority that is growing. Even during lockdown, arrests of children made up two-fifths (39 per cent) of total arrests for robbery in 2020. There has been a 72 per cent increase in the number of 16–18-year-olds admitted to A&E for knife wounds since 2014. I have no doubt that, if left unchecked, these trends will lead to a further growth in serious violence in the round.

This report performs an important public service in showing how the system has a particular blind spot when it comes to the most vulnerable children and adolescents. The child protection system is not able to adequately protect them or keep them safe from harm. Schools are incentivised to pass the buck by off-rolling or excluding difficult students from mainstream education. Too much child and youth offending is happening under the radar, unrecorded, meaning that when these children are entering the criminal justice system, they are doing so for committing more serious offences.

I am particularly struck by the findings from the Serious Case Reviews, which show so clearly yet again the failure or inability of multiple agencies to properly identify and respond to evidence of child criminal exploitation. In so many of these cases, it is clear we are missing opportunities to intervene at “reachable moments”, such as when a child returns from a missing episode, or the point at which they present at A&E with stab wounds. In many cases, these children are being exploited by gangs and are looking for a way out but are being denied that opportunity.

Rather than waiting until these children are murdered before carrying out Serious Case Reviews to understand lessons, we should be triggering those kinds of responses when the children are still alive.

For too long, there has been a fatalism about these problems within society and government. But violence involving children and young people simply is not inevitable, and while it is true that local government has been subjected to brutal cuts, this report shows that the solutions are not only about more money. They are about the system working more effectively, with a much greater sense of urgency from the top of government, starting with the Department for Education and the Home Office.

Society must always judge itself by the treatment of its children, the elderly and those that are vulnerable. This report shows we are letting children and young people down; but it also shows what we could do to divert and support children away from criminal exploitation and, later, offending and imprisonment. This is about safeguarding our children and stopping violent crime ruining victims’ lives.

Dame Louise Casey

Baroness Casey of Blackstock

Chapter 2

At the heart of the contract between citizen and state is an obligation that government will do everything it can to secure the safety of its citizens. It is an affront to that contract that serious youth violence has been allowed to spread through our cities and, increasingly, beyond to smaller towns. It is also dangerous. If people start to believe that violence is inevitable, they will stop bothering to report crime and the criminal justice system will lose public consent.

As we set out in our 2019 paper, Restoring Order and Rebuilding Communities: The Need for a New National Crime Plan, patterns of crime have shifted. While the big downward trends in “volume crime” such as burglary and car theft have broadly continued since 1995, there has been a substantial rise in lower-volume, high-harm offences such as knife crime and robbery, linked to shifts in the structure of the drugs market, including an expansion of “county lines” activity controlled by organised-crime groups. Increasingly, there is evidence that the age of those involved in violence – both perpetrators and victims – has fallen, alongside an apparent growth in the number of young people vulnerable to exploitation by gangs. Since 2014 there has been a 72 per cent increase in the number of 16–18-year-olds admitted to A&E for knife wounds.

Of course, serious violence covers a very broad range of offences and the majority are carried out by young adults. The focus of this paper is a subset of that problem: the involvement of children and adolescents in serious violence and the need for strategies to prevent such violence from occurring to begin with. We make the case for an ambitious national strategy – led by the Home Office and the Department for Education – to tackle the problem, involving reforms to child protection, schools and policing, as well as a complete overhaul in how services identify and respond to the issue of criminal exploitation. Ultimately, tackling the drivers of serious violence must be a collective endeavour, involving government, public services and local communities.

Key Findings

Younger people are increasingly involved in serious violence, both as perpetrators and victims.

In 2020, children accounted for two-fifths (39 per cent) of arrests for robbery.

Since 2014 there has been a 72 per cent increase in the number of 16–18-year-olds admitted to A&E for knife wounds (compared to a 25 per cent increase for adults).

At the same time, the pool of vulnerable young people has grown, creating a ready supply of people ripe for criminal exploitation by gangs.

There have been significant increases in the numbers of children taken into care, excluded from school and witnessing domestic abuse since 2015.

Covid-19 has exacerbated these trends, magnifying pre-existing vulnerabilities among children, particularly adolescents disengaged from school.

Case studies in child homicide and Serious Case Reviews suggest that at least five key warning signs offer lessons for agencies seeking to intervene.

The vast majority of homicide victims spent a large amount of time outside formal education.

There was often evidence of early-onset criminality, which appeared to be tolerated or neglected rather than dealt with.

Many perpetrators were clearly previous victims of serious violence and demonstrated evidence of criminal exploitation and coercion.

Nearly all had been reported as missing for extended periods of time, suggesting county-lines involvement.

In all cases, there was a failure to capitalise on a potentially pivotal “reachable moment”.

Our research suggests there are five systemic issues that need to be addressed.

The system is not set up to identify and respond to criminal exploitation, particularly adolescents trafficked into county lines activity.

The child protection system is primarily focused on risks to very young children inside the home, meaning adolescents at risk of violence in the community fall through the gaps.

Schools are failing to prevent the most vulnerable children from falling out of mainstream schooling, with exclusions and off-rolling still common.

Youth offending is being tolerated, rather than dealt with, meaning that early-onset criminality can proliferate into more serious offending.

Vulnerable adolescents are often not the responsibility of a single agency, meaning a lack of prioritisation locally.

Key Recommendations

The government should adopt an ambitious set of measures for tackling the causes of serious youth violence, including the following key recommendations:

Publish a new national strategy on the identification of and response to child criminal exploitation with clearly defined trigger points for intervention, including when children return from missing episodes and/or present at hospital with knife-related wounds.

Set out within the strategy national standards for local agencies in preventing exploitation, including limits on the placing of adolescents in unregulated accommodation miles from home, and ensuring police investigations examine the wider context surrounding violent incidents.

Reform child protection services to ensure greater emphasis on dealing with the risk of harm to adolescents in the community and intensive support for dysfunctional families.

Reform the funding arrangements for schools to ensure they are incentivised and resourced to keep vulnerable children in mainstream education, so that exclusion is used as a last resort and so that there is tighter monitoring of young people not in mainstream education and stiffer regulation of home-schooling.

Set new national standards on responding to youth offending, ensuring that early-onset criminality is dealt with, rather than neglected.

Put in place stronger governance and accountability to ensure that a single body – either Community Safety Partnerships or Violence Reduction Units – takes responsibility for preventing violence, rather than the current confusing patchwork of partnership bodies.

Chapter 3

Risk Factors for Serious Violence

It is a well-established criminological finding that a person’s background and upbringing are linked to their involvement in criminality.

A small minority of people commit the majority of crimes. Serious violence is no exception. While situational factors like alcohol and the degree of provocation are important drivers, personal circumstances while growing up can be a factor in giving some individuals a higher propensity for violence.

There is a large body of research on factors that predict or protect against violence. This evidence base has limitations, but some conclusions are clear:

Males commit the majority of serious violence. Of those convicted for homicide in the three years to March 2020, 93 per cent were male.[_]

Age is a key factor. While the number of those engaging in violence and the carrying of weapons peaks at the age of 15, a minority continue their offending beyond that age, and this group commits a large proportion of overall serious violence.[_]

Victim and suspect rates for serious violence vary by ethnic group. For example, in the three years to March 2020 average rates of homicide victimisation were around five times higher for black victims than white victims.[_] Despite this, the evidence on links between serious violence and ethnicity is limited. Once other factors (such as age and socioeconomic background) are controlled for, it is not clear whether ethnicity is a predictor of offending or victimisation.

Beyond these demographic factors, a range of other factors have been linked to both perpetration and victimisation of crime and violent behaviour. Figure 1 highlights a subset of these. It should be kept in mind that violent crime shares similar risk factors with other types of crime and antisocial behaviour and will also correlate with other poor life outcomes such as low educational attainment, poor health and unemployment.

Risk factors and proxy indicators for serious violence

Sources: Roe, S., & Ashe, J. (2008), Young people and crime: Findings from the 2006 Offending, Crime and Justice Survey; Dobash, R. P. et al (2007), Onset of offending and life course among men convicted of murder, Homicide Studies, 11(4), 243-271; Home Office (2019), An analysis of indicators of serious violence: Findings from the Millennium Cohort Study and the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study; McVie, S, (2010), Gang membership and knife carrying: findings from the Edinburgh study of youth transitions and crime; MoJ (2018), Examining the Educational Background of Young Knife Possession Offenders; Home Office (2018), Serious Violence Strategy. Dijkstra, J. K, (2012), Testing three explanations of the emergence of weapon carrying in peer context: The roles of aggression, victimisation, and the social network, Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(4), 371-376.

There is some evidence that risk factors for knife carrying are slightly different to those for gang-related crime. A longitudinal study carried out in Edinburgh[_] examined both gang membership and knife carrying and found some key differences. Young people who became involved in gangs were more likely to have experienced childhood disadvantage, including family poverty and living in high-crime neighbourhoods, than young people carrying knives, for whom peer influence and social norms were possibly more important factors.[_]

Trends in Serious Violence

Serious violence has been increasing since 2014. There is evidence that this is linked to a shift towards both younger perpetrators and younger victims.

In general, the regularity and severity of individuals’ offending will tend to decrease over time, as they get older. As a result, we tend to assume that the level of crime (and therefore violence) is correlated to the average age of offenders. When the average age of offenders falls, crime levels will rise, and vice versa.

When analysing current trends in violence, an important question to ask, therefore, is whether there is evidence of a shift towards younger offenders. Various data sources do indeed indicate a shift in that direction.

Figure 2 shows trends in cautions and convictions for knife possession. Between 2014 and 2019 there was a 56 per cent rise in knife possession offences for 10–17-year-olds, compared to a 36 per cent rise overall.

Offences involving the possession of a knife or offensive weapon resulting in a caution or conviction by age, 2014–2019

Source: House of Commons Library, Knife Crime Statistics. Note: figures for Q2–Q4 of 2019 are estimates that are subject to revision.

When it comes to the study of serious violence, robbery is a key offence to analyse. Studies show that those who commit robbery and use weapons before they reach the age of 18 are much more likely to have long criminal careers than young people who commit less serious crimes. Those committing robbery as a first offence are around three times more likely than fellow young offenders to go on to commit 15 or more offences within the next nine years.[_]

Not only is robbery increasing nationally, it appears that younger offenders are increasingly involved. Figure 3 illustrates that arrests of 10–17-year-olds are making up a growing proportion (39 per cent) of total arrests for robbery.

Recorded robbery arrests and proportion committed by 10–17-year-olds, 2015–2020

Source: Home Office, Arrests open data tables from the Police powers and procedures England and Wales year ending 31 March 2020. Note: Lancashire could not supply complete data for 2017/2018 and 2018/2019, and Greater Manchester could not supply data for 2019/2020.

While we do not have national data on the age of knife crime offenders, inferences regarding the age profile of victims can be made on the basis of NHS data. Victim age can be linked to the age of perpetrators, so the data provide some insight into offending patterns. The NHS data for England on assaults with a sharp object show that, since 2014/2015, the number of episodes involving individuals aged 16–18 has increased by 72 per cent. For those episodes involving individuals aged 19 and over, the equivalent increase was only 25 per cent.

Number of times hospital consultants treated people for assault by a sharp object, by age group, 2014-15 to 2019-2020

Source: House of Commons Library, Knife Crime Statistics. Note: figures for Q2 – Q4 of 2019 are estimates that are subject to revision.

In recent years, there has also been a big jump in the number of young adults murdered by a sharp instrument. Between 2015/2016 and 2019/2020, the number of 16–24-year-olds murdered by a sharp instrument rose by 86 per cent.[_]

In summary, there does appear to have been a wholesale shift towards younger offending, at least when it comes to serious violence. One reason may be spillover effects from violence associated with the drugs market. Evidence shows that if gangs start carrying more weapons due to drug-selling activity, others may also feel the need to arm themselves for protection. This can escalate violent trends, as it means any conflict is likely to result in a more serious outcome. Figure 5 suggests there has been an increase in the number of children being arrested for drug-related offences – potentially a good indicator of how many children are being exploited by gangs.

Indexed trends in child arrests (ages 10–17), 2012/2013 – 2019/2020 (100 = 2012/2013)

Source: Home Office, Arrests open data tables from the Police powers and procedures England and Wales year ending 31 March 2020. Note: Lancashire could not supply complete data for 2017/2018 and 2018/2019, and Greater Manchester could not supply data for 2019/2020.

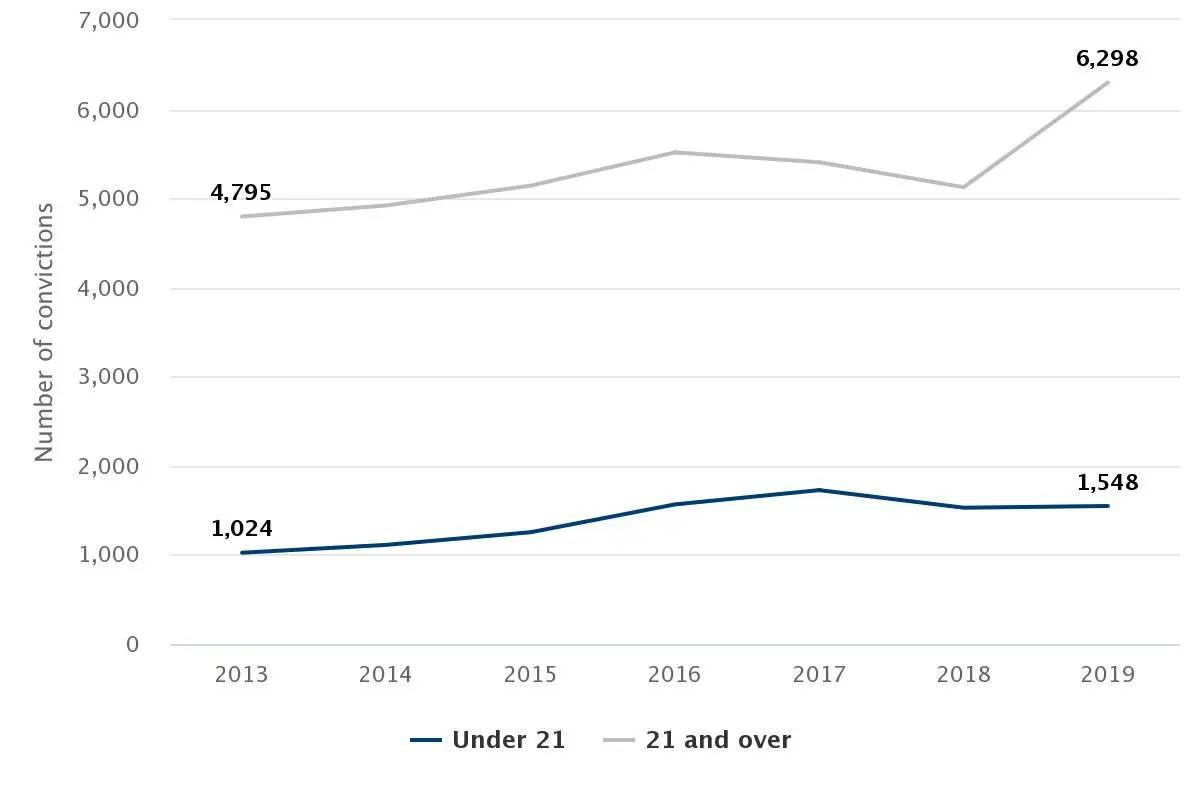

At the same time, the number of people under 21 convicted of Class A drug offences has increased by 51 per cent since 2013, compared to a 31 per cent increase for those aged 21 and over.

Number of convictions for principal offences of the production, supply and possession with intent to supply a controlled (Class A) drug, broken down by age, 2013–2019

Source: Ministry of Justice, Criminal justice system statistics quarterly: December 2019; Home Office, Experimental statistics: Principal offence proceedings and outcomes by Home Office offence code data tool, December 2017.

Mapping undertaken by the Children’s Commissioner suggests the number of children involved with gangs may be higher than many people commonly suppose. While only 27,000 children in England identify as gang members, a much higher number of children are thought to be on the periphery of gangs, making them vulnerable to grooming and exploitation. The Office of the Children’s Commissioner estimated that 313,000 children aged 10–17 know someone they would define as a street gang member.[_]

Trends in Vulnerability

At the same time, the pool of vulnerable young people has grown, creating a ready supply of people ripe for criminal exploitation by gangs. The evidence suggests that being in care, being deemed at risk of harm, school exclusion, domestic abuse and multiple deprivation – a combination of disadvantaging factors – are all markers for increased risk of both victimisation and perpetration of violence. While this does not mean there is necessarily a causal link between increases in the number of the most vulnerable and serious violence, these groups possess some of the factors that put them at higher risk of being exploited for offences such as drug market-related violence.

Analysing the data, we can see that there has been a significant increase in young people experiencing many of these measures. The number of children in low-income families has grown since 2014/2015 (from 2 million to 2.5 million in 2019/2020) to 18 per cent of all children in England.[_] Over the same period, the numbers of children taken into care and children deemed to be at risk of harm (defined by Section 47 local authority investigations taking place) have also grown significantly (Figures 7 and 8).

Rates of children looked after at 31 March, per 10,000 child population, 2015–2020

Source: Department for Education, Local authority tables: children looked after in England including adoption 2018 to 2019 and 2019 to 2020.

Number of Section 47 enquiries and rate per 10,000 children aged under 18, 2014/2015 – 2019/2020

Source: Department for Education, 2019, Characteristics of children in need, 2019 to 2020.

It is notable that the rate of permanent and fixed-term exclusions from school has also been rising since 2013/2014 (Figure 9).

The rate of children per 100,000 excluded from state-funded and special schools in England (2006/2007 - 2018/2019)

Source: Department for Education, Permanent and fixed-period exclusions in England, 2018/2019.

Police-recorded domestic abuse has risen by 89 per cent since 2015/2016, though this may be a reflection of more people reporting it and better recording. It is now estimated that around 830,000 children per year experience or witness domestic abuse in England.[_]

Number of police-recorded domestic abuse-related crimes in England and Wales, 2015/2016 – 2019/2020

Source: ONS, Domestic abuse in England and Wales year ending 31 March 2020, Tables 4b and 9. *Greater Manchester has been excluded for consistency.

It appears highly likely that the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated many of these risk factors. For example, while levels of domestic abuse recorded by the police had been rising for a number of years before the Covid-19 pandemic, Metropolitan police data suggest that calls for domestic abuse incidents rose significantly during the initial lockdown in 2020. (Looking at the total number of calls from 18 March to 2 June, numbers were up 12 per cent in 2020 compared to 2019. This increase comes entirely from third-party callers; calls from victims were down 3 per cent in the same period.)[_]

Similarly, teachers have reported concerns about teenagers becoming effectively disengaged from formal education following the repeated lockdowns of the past year. This is particularly acute in schools within deprived areas: teachers in schools in the most deprived quartile were more than three times as likely to say “less than a quarter” of their students had submitted the work that had been assigned to them.[_] School closures have left vulnerable children without a key protective factor as teachers are often the first to report abuse. Social care referrals fell by almost a fifth in the first lockdown, suggesting fewer children at risk were being identified.[_]

Chapter 4

Analysis of Serious Case Reviews

As the previous chapter illustrated, there are a number of adverse trends that suggest the problem is getting worse. But it’s hard to know what’s driving these statistics – and still harder to figure out what to do to turn them around with effective interventions – without getting into much more granular detail. So this chapter draws on homicide and Serious Case Reviews[_] to identify patterns and characteristics of homicide incidents and how services intervene to prevent such incidents, particularly in the run-up to them. For the purposes of this research, we have focused on two types of statutory review:

Serious Case Reviews (now called Child Safeguarding Practice Reviews): conducted when abuse or neglect is known or suspected, a child under 18 has died or been seriously harmed, and there is concern about safeguarding practice.

Domestic Homicide Reviews: conducted after the death of a person aged 16 or over from violence, abuse or neglect by someone to whom they are related, in an intimate relationship with or from within the same household.

Common Patterns and Themes

Our analysis of Serious Case Reviews and Domestic Homicide Reviews identifies at least four key warning signs and risk signals.

First, it was notable that all of the subjects had spent an extended period outside mainstream education, in some cases spanning several years. The transition from primary to secondary school often marked the onset of problematic behaviour, with secondary schools apparently less equipped (or possibly less incentivised) to offer wraparound support. The individuals involved had often been repeatedly excluded from school and disciplinary issues were identified as a common risk factor. In the case study below, the lack of any kind of regulatory oversight of home-schooling was singled out as a risk factor.

Case Study

Case Study 1: Serious Case Review into murder of Jaden (aged 14), Waltham Forest[_]

In January 2019, five men (one of whom has subsequently been convicted) knocked 14-year-old Jaden Moodie off his moped and repeatedly stabbed him to death in Waltham Forest.

Timeline

2004: born in Leicester. Father left home in the same year.

2016: transition to secondary school marked a worsening of behaviour, leading to multiple suspensions/disciplinary issues.

2017: home-schooled for a year at age of 13 (leading to “a lot of unsupervised time”). Mother became concerned by “bad influences” in the community and received threats about unpaid debts.

April 2018: mother moved Jaden from Nottingham to live with his grandmother in London (sleeping on grandmother’s sofa).

Oct 2018: “potentially pivotal moment” – Jaden arrested in a so-called cuckoo house in Bournemouth in possession of drugs (suggesting he was being exploited).

Three weeks later, Jaden was permanently excluded from school for a gun-related incident.

Local authority identified him as a priority for support, in need of a Children’s Social Care assessment and Youth Offending Service assessment – these were being arranged at the time of Jaden’s death.

There were delays rehousing Jaden’s mother (together with her son) and getting Jaden into full-time education.

Jaden was carrying a bag of drugs at the time of his murder.

Implications for Government

Lack of full-time education: Jaden spent all but three of his last 22 months out of school, and for much of this period there was limited adult guidance or supervision in regard to how he spent his time. Half of this time is accounted for by the period he was home-schooled.

Failing to capitalise on a “reachable moment”: the response to Jaden while detained in Bournemouth and then on his return to London in October 2018 was not sufficient for a child who was clearly being criminally exploited, and nor was all the information available from the authorities in Bournemouth transferred to their counterparts in Waltham Forest.

Duplication and confusion between agencies: by early January 2019, there were considerable numbers of professionals (at least five frontline case workers) involved with Jaden and his family, creating obvious risks of duplication and confusion. “When children are exposed to child criminal exploitation there is a strong argument for case discussion involving all agencies engaged with the child.” This never occurred.

Poor information-sharing: Nottinghamshire Police did not share information about Jaden’s gun-related incidents, nor about the reported threats made to his family about unpaid debts.

The Housing Service was not sufficiently engaged in multi-agency discussions: this meant there were delays in submitting Jaden’s mother’s rehousing application in Waltham Forest.

As the second key warning sign, in the majority of cases, the individuals concerned began offending at an early age. Offences ranged from possession of drugs to more serious offences involving knives, and serious sexual offences. However, in very few cases did the subject’s offending appear to lead to a criminal disposal, whether in the form of an out-of-court disposal or a formal caution or charge. This may have been due to a desire to avoid criminalising the individuals concerned. Many of the individuals were known to be operating under the influence of gangs (see below).

Case Study

Case Study 2: Serious Case Review into murder of Chris (aged 14), Newham[_]

On 4 September 2017, Chris was in Newham in a group of four young people. An unknown assailant passed by in a stolen vehicle and fired multiple shots into the crowd of young people; Chris received a bullet wound to his head and later died of his injuries.

Timeline

Born in 2003. Father left home while Chris was at a young age following reports of domestic violence.

Spent his early years living at various addresses, all temporary accommodation.

Diagnosed with ADHD and conduct disorder following several incidents at primary school (including threats to self-harm).

Behaviour at secondary school became increasingly unmanageable – leading to repeated fixed-term exclusions.

Jan 2016: Chris was referred to a pupil referral unit (PRU) aged 13.

April 2016: police reported concerns that he was being targeted by gangs – arrested for a serious sexual assault but not charged.

July 2016: PRU referred Chris to youth offending team (YOT) following reports he had bought a ‘Rambo knife’ and had a growing obsession with knives online.

Nov 2016: reported to have gone missing for a week.

Children’s social care records from that time point to Chris being groomed to sell drugs by older gangs.

Jan 2017: moved in with uncle in Lewisham – education disrupted.

April 2017: Chris was arrested (and convicted) for possessing a knife.

Implications for Government

Assessments are not the same as effective intervention: Chris’s family were not “hard to reach” – indeed, they asked repeatedly for help. The review’s conclusions are damning: “Despite hundreds of professional hours provided by a multitude of people, discussion at dozens of meetings over several years and provision of multiple forms of support (albeit with limited intervention), little changed for Chris and risk was not effectively managed ... poor-quality assessments and reviews were regularly confused with intervention.”

The contrast between primary and secondary school is stark: his primary school provided him with extra help (and his attendance was excellent) but this was not replicated at secondary school, with the review finding “little evidence that his SEND [special educational needs and disabilities] were fully understood or met.” Within two years he was referred to a PRU, where he met boys who led him into criminal activity and exploitation.

Early-onset criminality (from the age of 12 onwards) was not acted upon: he was caught committing many crimes but, aside from a single offence of knife possession (the year before he died), was not charged or even referred to specialist agencies.

The system knew there was a problem but was unable to act urgently: when Chris’s mother tried to get Chris rehoused due to fears of criminal exploitation, the housing association took too long to act on her application.

The current safeguarding model isn’t fit for purpose since it is premised on abuse within the home, whereas for Chris, the biggest risks were clearly outside the home.

Third, in nearly every case studied, evidence of criminal exploitation by gangs was clear and visible, with individuals and/or their families frequently expressing fear for their physical safety. For example, several case studies reported that in the weeks and months preceding their murder, the subject had been

threatened due to unpaid debts

the victim of violence (and had attended hospital for physical injuries)

found with large quantities of drugs

More than once, individuals were reported to have returned from a missing episode displaying signs of sudden wealth, such as new trainers or more than one mobile phone. Often, though, the response was rudimentary at best, and safeguarding services reported feeling “powerless” to do anything to intervene.

Case Study

Case Study 3: Serious Case Review into death of Jacob (aged 16), Oxfordshire[_]

In April 2019, Jacob was found dead in his bedroom. The coroner’s report recorded that Jacob was intoxicated and distressed, with insufficient evidence that he had intended to end his life.

Timeline

2003: born in Oxfordshire – relocated to the North East in primary school years with mother (father absent).

2014: referred to alternative education provision (aged 11).

2016: diagnosed by Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) as having ADHD (aged 14).

2017: returned to Oxfordshire with mother.

April 2018: fearing for Jacob’s and her own safety, Jacob’s mother moved him into care – but he was refused a secure placement and initially placed in unregulated accommodation (hotels).

For the 22 months prior to his death (following the move to Oxfordshire) Jacob was subject to significant escalating risks:

not on roll at any educational establishment.

offended multiple times (there are 26 separate police reports where he is recorded as a suspect or offender).

attended hospital for significant physical injuries (attending A&E three times with cuts and bruises).

went missing repeatedly (more than 20 times).

demonstrated evidence of being criminally exploited (possessing three mobile phones and large amounts of cash).

Oct 2018: returned home under a Supervision Order.

Implications for Government

Despite knowing criminal exploitation was occurring, services did not know how to combat it: the fact that Jacob was being groomed and exploited was well-known to professionals but while “they tried their best to help him … often they did not know how to do this.“

Lack of full-time education: the review concluded that Jacob was “let down by the education system” – despite spending nearly two years (22 months) off-rolled, his situation was never escalated by children’s social care.

Early-onset criminality was not dealt with: police records are extensive. There are 26 police reports where Jacob was recorded as a suspect or offender for mainly violent crimes (towards his mum and when in care). But Jacob was not placed before the courts, or subject to any criminal orders, or under supervision of the YOT.

Safeguarding services understood the risks but failed to act upon them urgently enough: Jacob was subject to nine strategy discussions during the year before his death. The records show these mostly recommended “a further period of monitoring”. Similarly, Jacob was discussed seven times at the multi-agency Missing Children’s Panel, but records show the outcome was typically “to review matters in a month’s time”.

Failure to capitalise on “reachable moments”: Jacob attended hospital with severe injuries on several occasions and expressed fear for his safety, but this was never acted upon.

Fourth, a common risk factor was services reporting the individual having repeatedly gone missing – in one case, as many as 20 times in the space of a year. Reviewing the case studies, two points stand out:

Missing episodes appear to steadily increase when the individual concerned is in a care setting, suggesting the family can be a protective factor.

In most cases, missing episodes are an indication that the individual concerned is being exploited by gangs to sell drugs, either locally or via an established county line network.

“Reachable Moments” and Missed Opportunities

A “reachable moment” is a concept taken from education, where it is called a “teachable moment”, and describes an unplanned opportunity that arises in a classroom where a teacher has a chance to offer insight to her or his students. In other areas of life, the same opportunity can be called a “reachable moment” and constitutes the same opportunity to break through a carefully constructed façade that is resistant to the development of personal insight.

In all of the case studies reviewed for this report, there was a clear failure by local services to capitalise on a potentially pivotal “reachable moment”. For example, in October 2018, Jaden (aged 14) was arrested, along with another 18-year-old boy, by Dorset Police in a property in Bournemouth that was allegedly being used as a so-called cuckoo flat by an organised-crime group for the illegal drugs trade. At the point the arrest was made, there was significant evidence of drug use and sales being made in the flat. Jaden himself was found to be in personal possession of 39 wraps of crack cocaine, a mobile phone and £325 in cash. The appropriate adult assigned to the case later recalled Jaden “appearing as a vulnerable young person frightened by what he was being groomed and coerced into by others, including the co-defendant … He gave me the impression that he definitely wanted to find a way out of the mess he was getting into.”[_] Jaden was subsequently released from custody at 3am to be returned to the care of his family in Waltham Forest. He was driven back to London by two police officers, arriving at his grandmother’s house at 5am on 26 October.

The author of Jaden’s Serious Case Review concluded that this episode represented a “missed opportunity”.

“Had it been possible for Child C [Jaden] to have met specialist child exploitation workers while still in custody, and then brought back to London by these workers, and ideally if they could have continued to work with him for a time after his return, I believe such workers would have been able to exploit the “reachable moment” of this crisis in the police station, during the car journey, and then subsequently, and start exploring with Child C the risks to him of his vulnerability to exploitation.”[_]

But this was not the brief of the Dorset police officers who were providing a well-intended but basic service in driving Jaden back to London.

Similarly, several months before he was murdered, Chris (aged 14) self-disclosed that he was mixed up in the drugs trade, with suggestions of gang involvement, and didn’t know how to stop. In November 2016, Chris went missing for a week, returning with new clothes and expensive trainers, but did not have an independent return interview. The author of Chris’s Serious Case Review concluded that:

“There were clear indicators that Chris was being exploited, as well as making some risky decisions, not mutually exclusive concepts if the victim/perpetrator overlap is understood … However, there seems to be little evidence that agencies effectively responded to Chris’s experiences as a victim.”[_]

It ought not to take a child’s death – and the subsequent Serious Case Review – to illustrate the importance of acting on reachable moments such as these.

What these cases illustrate is a pattern of failure in current support systems and the interaction of the various agencies involved in the protection of vulnerable adolescents. In the next chapter we analyse the gaps in the government’s response.

Chapter 5

Learning Lessons from Serious Case Reviews

The learning from these reviews points to five systemic issues that need addressing:

Child protection: children’s social services are not currently set up to protect children and adolescents at risk of harm outside the family home.

Criminal exploitation: neither the police nor social services are effective in identifying and responding to evidence that children are being groomed and exploited.

Education: schools are not equipped (or incentivised) to deal with poor behaviour, leading to exclusions and off-rolling more often than necessary, which heightens the risk of violence.

Youth offending: early-onset criminality is neglected rather than dealt with, meaning we are missing opportunities to intervene early, and the multi-agency YOT model has been diluted.

Governance and accountability: local accountability for preventing violence is weak – services are in silos.

These issues are examined in greater depth below.

Child Protection

On paper, there is a comprehensive and robust legal framework for the protection of children in England – set out in the Children Acts (1989 and 2004). In particular:

Section 17 of the Children Act 1989 puts a duty on local authorities to provide services to children in need for the purposes of safeguarding.

Section 47 of the Children Act 1989 requires a local authority to make enquiries and take action if there are concerns around child protection (reasonable cause to believe the child is suffering and/or likely to come to harm).

Section 31 of the Children Act 1989 states that Care and Supervision Orders allow a local authority to take a child into care if necessary.

But in practice, the child protection system has evolved to protect children from harm experienced within the family home.[_] This is reinforced by the legal framework, as well as the culture and practice of social work.

The legal provisions specify that when instigating care proceedings, the local authority must show that the harm to the child is attributable to the care and control provided by parents. For a child who is at risk of violence from outside the home, this will rarely be solely down to the actions of parents. Social workers may therefore be reluctant to start a process where there is no further escalation point.

Culturally, social workers identify with a mission to protect vulnerable children (as they imagine them) and can therefore struggle when they find themselves working with teenagers on the cusp of violence who don’t fit the conventional image of vulnerability.

Social workers are trained to recognise family abuse but are not necessarily equipped to deal with peer abuse, exploitation or serious violence. They may also feel that they have fewer legal and procedural levers over the external environments in which significant harm is present – whether that be a local park or school – than they do in family settings.

There are also resourcing constraints. For example, CAMHS clearly play an important role in supporting children and young people with mental health problems, many of whom will overlap with the cohort focused on in this paper. However, in recent years CAMHS have often struggled to meet local demand. It was reported that in 2017 more than 338,000 children were referred to CAMHS, but less than a third received treatment within the same year.[_]

There are innovative approaches that seek to address these problems. In particular, a new approach to protecting young people at risk – contextual safeguarding – looks promising, but there are real barriers to widespread adoption of the model.

The Contextual Safeguarding Model

A review of safeguarding responses identified that risks to young people’s welfare increased in their peer relationships, schools and neighbourhoods, whereas safeguarding assessments and interventions targeted individual young people and families affected by those contexts. The review concluded that child protection systems were failing victims at risk of abuse in non-family settings.

The contextual safeguarding model describes an approach to child protection in which extra-familial contexts, and the interplay between them and their varying weight of influence on young people’s decisions, become the target of assessment and intervention.[_]

Projects are currently being piloted in a number of London boroughs focusing on those at risk of child sexual and criminal exploitation, peer-on-peer abuse, youth violence and involvement with gangs.

The findings of an evaluation in 2020 were mixed – while there were signs that social workers were more aware of, and confident about, recording harm in non-family settings, many continued to struggle with the culture change under the new model.

Criminal Exploitation

Neither the police nor safeguarding services are currently effective at identifying and responding to evidence of child criminal exploitation.

With respect to policing, there is sometimes a failure to see the bigger picture with regards to exploitation. Analysis of case reviews and interviews with local authority stakeholders suggest that police investigations into violent incidents often focus narrowly on identifying suspects and do not always prioritise generating insights into the broader context within which the offence took place, including possible networks of exploitation.

This is partly about lack of information: the police are often unable to pinpoint the exact causes and/or motives for serious violence, with some communities particularly reluctant to “talk”. But it is also linked to incentives: policing is generally driven by short-term tactical concerns – clearing the case – rather than strategic analysis relating to underlying motives or patterns of exploitation. As a lead member for community safety in a London borough put it:

“Detectives go where the evidence is – phones, CCTV, forensics, witnesses (if they talk). Motive? They don’t need to prove that, so it’s not a priority, and it’s a lot harder to establish WHY when young people don’t talk. Hence there are huge gaps in understanding.”

The situation with safeguarding services is just as problematic, in that local authorities appear to be inadvertently creating the conditions for exploitation by placing looked-after children in unregulated or unregistered accommodation, often far from home. Figure 11 illustrates the growth in such placements.

Percentage change of children looked after at 31 March, 2015–2019, broken down by location of foster placement and placement in children’s homes

Source: Department for Education, Children looked after in England including adoption: 2014 to 2015 & 2020.

Placements in accommodation not regulated by Ofsted have risen by 125 per cent since 2015, to a total of 2,790 placements in 2019. Placements in residential care outside a child’s home authority have gone up by nearly a quarter. Adolescents in unregulated settings are more likely to end up becoming involved in county lines activity, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation and violence.[_]

Education

One of the most important and best-evidenced protective factors against serious violence is ensuring children stay in full-time education. However, the performance and funding systems for schools do not incentivise them to prioritise improving outcomes for the minority of vulnerable children who require high levels of specialist support.

When a child is excluded from school, more expensive alternative provision – for example, through a pupil referral unit – is paid for by the local authority.[_] The unit cost is estimated at £17,000 per pupil.[_] The excluding school is no longer responsible for the costs of that provision or for educational attainment. This means there is little financial incentive for schools to try to manage the problem themselves.

“Simply put, if a child is displaying behaviour or performance that requires additional management and support, it is often easier and cheaper to permanently exclude them, than for the school to implement what they need.” – Respondent to the Timpson Review (2019).[_]

It is, therefore, perhaps unsurprising that informal practices, such as fixed-term exclusions and off-rolling are becoming more common, particularly for children in care and children deemed to be in need. A 2019 survey for Ofsted[_] found that while schools may say to parents that pupils are off-rolled due to behaviour, teachers privately believe the decisions are taken to boost the school’s academic record. Teachers who have seen off-rolling also believe the practice is on the rise. At the same time, cuts to local authority budgets have meant that Special Educational Needs (SEN) provision has struggled to keep pace with demand.[_]

Youth Offending

Over a decade ago, alarmed by high rates of youth custody, the Youth Justice Board (YJB) set a specific target to reduce the numbers of ‘first time entrants’ into the criminal justice system. By their own measure, the YJB has achieved phenomenal success: first-time entrants into the criminal justice system have fallen by 84 per cent since the year ending December 2009.[_]

However, in recent years concerns have grown that this may have inadvertently led to early-onset offending being neglected or overlooked. Policing leaders have openly speculated as to whether the fall in sanctions for low-level youth offending may have reduced deterrence, inadvertently fuelling more serious crime. For example, Met Police Commissioner Cressida Dick stated that some children who offend are “simply not fearful of how the state will respond to their actions” and that “harsher, more effective” sentences are required to deter this group of repeat child offenders.[_] As one YOT manager put it in an interview, the tolerance of early-onset offending meant that “by the time young people are on a court order they are more prolific and entrenched in their offending”.

It is notable that children appear to be entering the system at a more serious offending level: in 2019, 18 per cent of children entering the justice system for the first time committed a possession of weapon offence – compared to just 3 per cent ten years ago.

The proportion of juveniles convicted or cautioned for a violence against the person offence that were first-time entrants, year ending September 2009–2019

Source: Ministry of Justice, Criminal Justice System statistics quarterly: September 2019.

Paradoxically, the desire to avoid labelling young offenders may actually lead to fewer young people receiving the support they need. In his annual report published in 2020, the Chief Inspector of Probation Justin Russell commented:

“A policy of ‘radical non-interventionism’, as it was termed in social work circles in the 1970s, may avoid the danger of children becoming labelled as offenders. But it does little to provide them with practical help with their underlying needs and may, in reality, amount to something more like benign neglect, in the absence of any other support or structure in these children’s lives.”[_]

The model established under the Labour government – of dedicated, multi-agency YOTs managing young offenders – has been diluted in recent years. In many parts of the country, YOTs have been swallowed up within children’s services, motivated by apparent falling demand (fewer first time entrants) and the need to achieve financial savings.

The risks of this dilution are illustrated by the example of Surrey, which restructured its youth services in 2012, merging its youth offending team within a Youth Support Service to sit within broader children’s services. Prior to the restructure, Surrey received a positive core case inspection in 2011. However, an inspection in 2019[_] rated Surrey’s youth offending services as “inadequate”, placing it in the bottom 10 per cent of youth offending services. The inspection’s findings often centred around the negative effects of losing the specialism of YOT workers, which affected the service’s ability to adequately safeguard and manage risk: “We were not satisfied that staff had the level of knowledge, experience or understanding required to respond to issues of safety and wellbeing and risk of harm to others. Work to ensure the safety of children and young people and to manage any risk of harm to others was inadequate.”

Governance and Accountability

Local accountability for tackling the causes of violence is fragmented; even when young people are identified as presenting a significant risk, the system is often too slow to respond. There are two interrelated problems.

First, children not considered to be “at risk enough” fall through gaps in support. For example:

Local services – whether child protection, police or youth offending teams – have no legal responsibility to identify and support child victims of violence.

There is no real-time monitoring of children who are out of school for safeguarding purposes. Such data – on exclusions and off-rolling – is not routinely shared.

Children turning 18 who have been supported under child protection arrangements are not automatically transferred to adult safeguarding services, leading to a cliff-edge in support.

There is no established means to ensure services are able to capitalise on “reachable moments” in a child’s life.

Second, no one has ultimate responsibility for prevention, with funding for early intervention projects reinforcing silo working:

Decision-making and services for vulnerable children are split between many partnership bodies, including Health and Wellbeing Boards, Local Safeguarding Boards and Community Safety Partnerships.

No agency takes overall responsibility for preventing children becoming victims or offenders.

The government funds specific initiatives such as the Youth Endowment Fund (£200m over ten years), the Early Intervention Youth Fund (£22m over two years) and the Trusted Relationship Fund (£13m over two years). However, they are not adequate replacements for core funding and can lead to duplication.

Targeted early help for dysfunctional families has been proven to be an effective means of preventing crime (and therefore violence). For example, the Troubled Families Programme, which grew out of earlier efforts by the last Labour government to pioneer family-based interventions focused on the most dysfunctional families, is now a core part of the early-help provision in most areas of England. Under the programme, services are delivered through a “whole family approach”, with support to deal with unemployment, ill health, vulnerability, domestic abuse and crime.

The premise of the programme is that for a minority of dysfunctional families, a different kind of model is required: more intensive, persistent and breaking down the silos between agencies and professions (housing, social services, policing). Government has estimated that the average cost saving to the taxpayer per family was £12,000 – more than twice the average cost of the intervention (£5,493).[_] However, due to high caseloads (and, more recently, challenges around engaging the police), the Troubled Families Programme has tended to prioritise families with younger children.

In summary, what we see is a patchwork of service provision where cuts to local budgets, combined with each service’s own cultural comfort zone, has led to gaps opening up. And it is vulnerable children and adolescents who are increasingly slipping between them.

Chapter 6

Below, we identify a series of policy recommendations that would address the core problems identified in the previous chapter.

A National Strategy on Child Criminal Exploitation

The Home Office and the Department for Education should jointly publish a national strategy focusing on the identification of and response to child criminal exploitation. The strategy should set out a clearly defined set of circumstances, which will trigger a formal response coordinated by the local authority to get help to the child and/or family concerned, such as:

when a child returns from a missing episode’ displaying visible signs of exploitation, such as expensive new clothes or more than one phone.

when a child (who appears to be linked to a county lines network) is arrested by the police some distance away from their home, offering a potentially “reachable moment”.

when a child presents at A&E with knife-related wounds, suggesting involvement in serious violence.

This will ensure that the system is able to respond to potentially “reachable moments” in real-time, rather than having to wait until Serious Case Reviews are published many months after the child has died.

In addition to the above, the strategy should establish national standards with respect to the activities of local authorities and police, regarding:

the placement of adolescents in unregulated care homes miles from home, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation.

police investigations into violence, ensuring a focus on the broader context surrounding violent incidents and an analysis of social networks.

Reconfigure Children’s Social Services to Deal with Violence Outside the Home

In response to the increasing number of children taken into care, the government has commissioned an independent review of children’s social care, led by Josh MacAlister, to recommend ways to reduce the number of children entering care unnecessarily, while also improving the experience of care for those children who become looked after. Given the rising numbers of adolescents entering care through arrangements based on Section 20 of the 1989 Children Act due to extra-familial risk, and the generally poor outcomes for young people who enter care in adolescence, this review offers an opportunity to address multi-agency responses to extra-familial harm, reforming child protection procedures and practices to address violence in the community. Our analysis suggests this should include:

Encouraging new practice models, such as contextual safeguarding, which apply multi-agency approaches to identifying and responding to risks of harm outside the home.

A focus on multi-agency early intervention support for families and young people at risk below thresholds for statutory intervention, building on the Troubled Families Programme.

A new legal requirement to set out an action plan for adolescents deemed at risk of criminal exploitation.

Local plans to address the risks facing vulnerable adolescents, which reflect the particular circumstances and hazards within localities.

Resource and Incentivise Schools to Invest More in Managing Poor Behaviour

School-funding arrangements should provide incentives for schools to invest more in managing poor behaviour and ensuring vulnerable children aren’t able to fall out of education entirely:

When pupils reach a threshold of fixed-term exclusions, which puts them at risk of permanent exclusion or being withdrawn from the school, this should trigger a multi-agency meeting involving school leaders, the police, youth offending team and safeguarding services.

Schools should be responsible for a child’s attainment when excluded and jointly responsible for funding the cost of alternative provision with the local authority.

Government should consider introducing a new “vulnerability” premium for schools to provide additional support for children designated at risk of harm/exploitation.

Safeguarding services should have access to real-time information about children not currently in school.

Alongside the reforms above, regulation of home-schooling should be tightened, with a national register for home-schooled children and minimum standards to be met.

National Standards on Dealing with Youth Offending

The government should set out new national standards in relation to early-onset criminality. The strategy should cover the following three areas:

Diversion: a review of current approaches to diversion and out-of-court disposals to ensure that early-onset criminality is being dealt with, rather than tolerated. Specifically, this should include a focus on whether the target to reduce first-time entrants into the criminal justice system has inadvertently led to a policy of non-interventionism.

YOTs: clarifying guidance to ensure that the distinctiveness of the YOT model – including the multi-agency approach – is retained by local authorities and not swallowed up by children’s services.

Gangs: examining innovative new powers to tackle the influence of gangs, using the latest technology, for example to monitor the movement of young people exploited by county lines networks using public transport.

Establish Stronger Governance and Accountability

Locally, there is a confusing patchwork of prevention-oriented partnership bodies, including Violence Reduction Units, Community Safety Partnerships and Local Safeguarding Boards. Government should consult on how best to simplify and sharpen local governance arrangements, ensuring a single body is charged with preventing youth violence locally, underpinned by the new duty to cooperate to prevent serious violence. This body could either be Community Safety Partnerships (though they would need to be rejuvenated in their current form) or Violence Reduction Units (presently still in their infancy).

Nationally, government should establish a cross-government taskforce to join up all the various departments of government to tackle the causes of violence, including representatives from the voluntary sector and wider communities, reporting jointly to the Prime Minister and Home Secretary.

To conclude, serious violence involving children is not inevitable and the solutions aren’t enormously complicated. Tackling it needs to start with a conscious recognition of the fact that no single agency or service can solve the problem on its own. There needs to be concerted cross-agency effort to take ownership and close the gaps. Post-pandemic, it is likely that resources will continue to be tight, but a great deal can be done without more spending. What’s clear is that if we don’t act urgently to address the problem, the costs of crime will mount.

Lead Image: Getty Images

Charts created with Highcharts unless otherwise credited.