Faced with the pandemic, businesses were forced to close offices and quickly implement new working practices. For office workers, it meant a shift to working from home: Zoom usage soared to 300 million daily participants in April 2020 compared to 10 million in December 2019.

Yet the impact of remote working and job losses has been uneven, hitting younger, female, and frontline workers the hardest. Firms are having to rethink their corporate culture even as they make tough decisions about cutting costs. And there are signs that people are moving away from cities, with potentially significant social and economic consequences.

The move to remote working is unlikely to be the last evolution in the world of work: shifts in technology and globalisation, left on their own, could see an expansion of informal, flexible, yet insecure work at the expense of traditionally safe, well-paid white-collar jobs.

Both business and government need to understand and harness these shifts in order to maintain the benefits of new technologies, while limiting their precarity. Failure to do so would risk widening labour market insecurity and feeding populist and protectionist demands from middle-class workers.

The longer-term this shift may be nothing to smile about

From Alfred Marshall to Alan Krueger, economists have long understood that technological shifts, if left solely to market forces, typically strengthen winner-takes-all dynamics, benefiting the few individuals or companies that can operate at scale and depressing wages and revenues for those that can’t. One way to think about these dynamics is through the Smiling Curve, which describes value generation in sectors such as manufacturing and publishing.

For manufacturing, the Smiling Curve illustrates how the ICT revolution enabled companies to disaggregate higher-value R&D (the left-hand tip of the smile in Figure 1a) and specialised customer knowledge (the right-hand tip) from lower-value, commoditised production (the bottom of the smile), which was offshored to lower-cost economies. For publishing, the Smiling Curve captures how technology reshaped value generation, benefiting creative individuals and content aggregators (eg Google and twitter) at the expense of traditional newspapers (at the bottom of the smile).

Figure 1a The Smiling Curve in Manufacturing

Source: Stratechery

Figure 1b The Smiling Curve in Publishing

Source: Stratechery

What can the smiling curve tell us about the UK economy?

To understand how the Smiling Curve applies to the UK, it’s worth looking at some stylised facts about the economy over the past decade.

Through the 2010s, shifts in technology and globalisation supported the growth of superstar companies, such as Deliveroo and Google, capable of leveraging data, ideas, and networks to increase their market share, markups, and wages. These shifts also created a new cadre of superstar individuals, such as Zoella, who leveraged the network effects of social media platforms to turn celebrity and influence into wealth.

Advances in technology also opened up new business models, enabling an employment boom built on lower-paid informal and gig jobs which offered greater flexibility but also increased insecurity. In addition, smaller firms were less likely to invest in digital technologies, so saw their productivity lag behind the larger superstars.

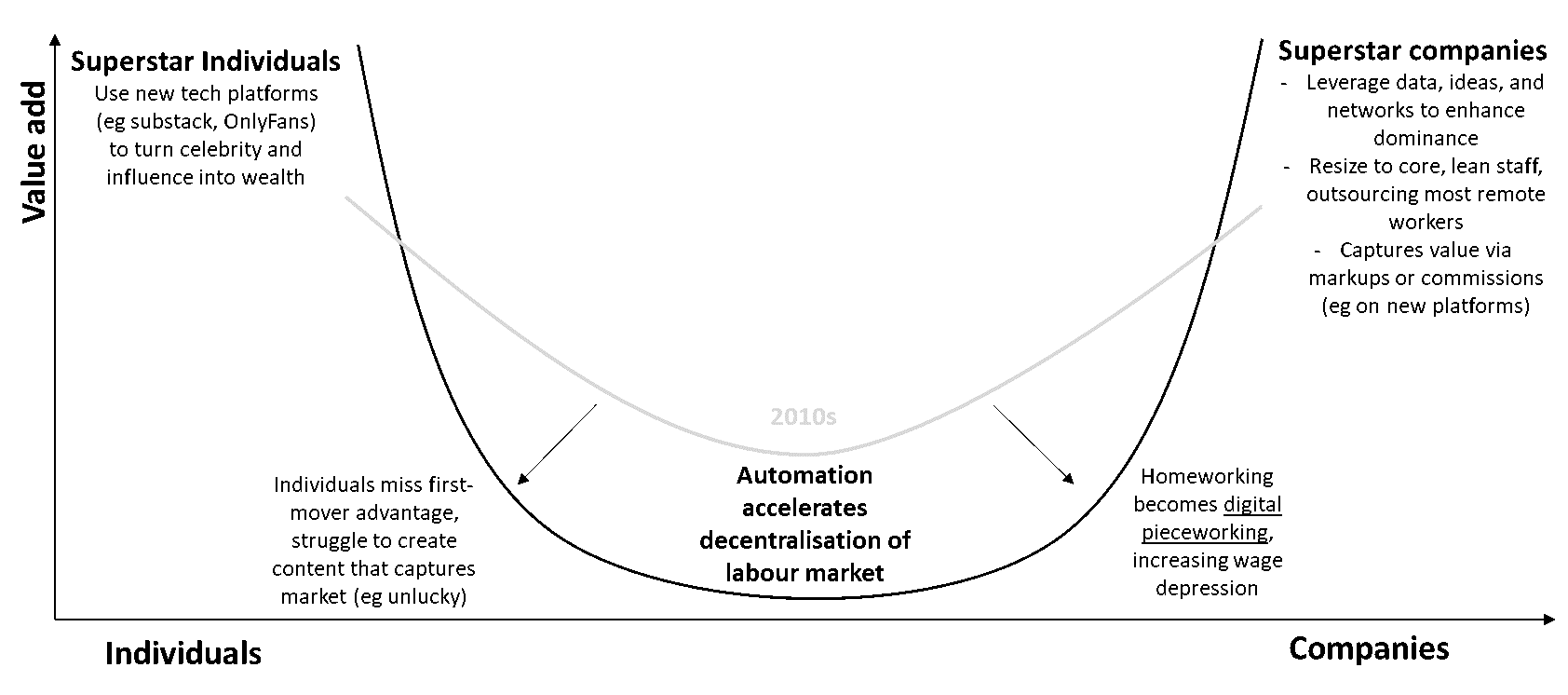

We can map these trends to the Smiling Curve (see Figure 2), if we think of the horizontal axis as the distribution of economic actors, from individuals at one end to large multinationals at the other. The superstar winners over the past decade are at either end of the smile, with individuals in lower-paid gig jobs and lower-productivity businesses struggling to create the same value at the bottom.

Figure 2 Mapping the UK economy in the 2010s to the Smiling Curve

Source: TBI

From pandemic to precarity?

The pandemic has accelerated tech development, potentially exacerbating last decade’s winner-takes all dynamics. Against a backdrop of increased remote working and massive job losses, new tech platforms are further decentralising labour markets. Jobs that can be done from home, can potentially be done for cheaper elsewhere in the world. Firms worried about costs may opt to employ only the core staff required for in-person collaboration and decision making. This could then put many UK white-collar jobs at risk of being outsourced to digital piece-working platforms or shifted abroad, much like manufacturing jobs in the 1980s and 1990s.

For individuals, the pandemic has accelerated competition for content creators to generate value via platforms such as Substack, Twitch, and OnlyFans. But not every newsletter, gamer, or artist will succeed in becoming superstars, leaving the vast majority competing in an increasingly decentralised workforce.

Mapping these trends on to the Smile Curve (see Figure 3), what we’re likely to see is a deepening of the curve, as superstars are able to create and extract ever more value, while broadening the base of workers competing on an expanding array of digital platforms for relatively lower-paid, flexible yet insecure work.

Figure 3 The post-Covid economy could deepen the Smiling Curve

Source: TBI

Going back to work will never be the same

Nothing about these shifts are inevitable. While remote working is likely, at least to some degree, to become a permanent feature, both businesses and governments can work together to understand and harness these shifts by addressing the following issues:

Rethinking the social contract. This shouldn’t mean simply classifying all gig workers as employees, as in the failed Prop 22 ballot initiative in California. Rather, both business and government need to be prepared to offer a new social contract – from a new social safety net and training regimes, to modernised regulatory and tax systems – that maintain the benefits of new technologies but limit precarity and promote security.

Understanding which jobs are at risk of being moved abroad. Until recently, professional jobs had been relatively sheltered from globalisation. Yet, offshoring white collar jobs could see greater calls for protectionism (as already seen in Singapore). Identifying which jobs – and in which sectors and regions – are at risk is the first step to ensuring well-paid, remote jobs can remain in the UK, supporting prosperity across the country.

Improving UK management capabilities to handle a world of remote working. The move to remote working places a premium on management and leadership. Yet the UK typically ranks relatively low internationally for management skills. Understanding and addressing this challenge will be necessary to ensuring the UK remains a globally competitive destination for increasingly mobile knowledge workers and business investment.

Going back to work will never be the same, and, in the coming months, the Institute will be exploring these issues so that business and government can seize this opportunity to rethink the future of work.