Our AI for Climate series explores what an AI-enabled climate policy programme could look like in the UK, examining how AI can make climate action faster, cheaper and fairer, and how the government can prepare to lead in applying AI solutions to climate change.

The clean-energy transition won’t be achieved by turbines on hilltops or electric-vehicle (EV) rollouts alone. It will be achieved when clean electricity turns up as lower bills and fewer hassles for people. That depends on how the system evolves, and particularly how it integrates artificial intelligence. This technology could help create a system in which market design, data integration and regulation enable cheaper, clean power to flow easily to homes and businesses – but if these layers continue to operate in siloes, they will remain trapped in inefficiency.

Rethinking markets, modernising regulation and building digital infrastructure that centres the consumer aren’t ribbon-cutting projects, but the government’s success or otherwise in doing so will determine whether the transition feels easy and affordable or clunky and costly.

Public support for climate leadership rests on that difference. Ipsos polling from 2024 shows backing for climate action remains strong, especially for practical, money-saving measures like improving home efficiency.[_] But support is more cautious than it once was, shaped by high bills and cost-of-living pressures, with many people expecting the transition to bring short-term costs. This creates a fragile consent environment in which people will only back green growth when government can show how bills stay predictable, when processes are simple, and when benefits are visible in homes and communities.

AI can do this by making the system work for people. It can turn data into action so households and businesses automatically use the cheapest, cleanest power available, without needing to track energy tariffs or timings themselves.

Today, too often, the opposite happens. Consumers bear the costs of a system that fails to use clean power when it’s available, losing out not only in the form of constraint payments to clean-energy generators when there isn’t enough grid capacity for their power, but also in higher network charges and the wider costs of relying on more expensive generation. This year in Britain, more than £346 million has been spent on wind curtailment because the grid couldn’t absorb excess generation,[_] with costs expected to reach £8 billion by 2030 if nothing changes.[_] Electrification will add further pressure as demand for EVs and heat pumps grows, driving more reinforcement and higher costs unless demand is managed more smartly.

AI can change this equation. Used responsibly – with clear consent, transparency and control[_] – AI can make systems efficient in a way that people can feel. It can forecast supply and demand, balance generation and storage in real time, and coordinate how power is used across homes, fleets and factories so that cheaper renewables are not wasted. It can also automate the back-end processes – verification, settlement and data exchange – that turn those efficiencies into visible savings on bills. The result is not a new layer of technology for people to manage, but a smarter system that quietly lowers costs and improves reliability. Done well, it turns a system that informs people when power is cheaper into one that automatically makes it cheaper.

That change is already starting to take shape. For businesses, startups like Q Energy offer AI-optimised “smart battery” tariffs that guarantee around 10 to 25 per cent savings on electricity bills when paired with on-site storage.[_] For households, similar efforts are emerging via smart EV-charging and flexible tariffs.[_] Together they show what is possible when automation and market design work in sync by using system intelligence to create consumer simplicity.

The government should work across four key pillars to make this future real: Markets, Regulation, Data and Consumers. The first three create the conditions for change; the fourth, delivering for households and businesses, is where people feel the benefits.

The UK already has much of what is needed: strong renewable resources, millions of smart meters, functioning markets, global leadership in AI and a public sector willing to lead. It is focus and follow-through that are missing. To unlock AI’s full potential, government must lean harder on its own delivery system, using energy regulator Ofgem, the Department for Energy Security & Net Zero (DESNZ), the Department for Science, Innovation & Technology (DSIT), and the National Energy System Operator (NESO) to drive regulatory and market innovation, not just oversight. That means modernising market design, regulation and data infrastructure so AI can quietly coordinate supply, demand and flexibility in the background, and aligning energy and digital policy so efficiency and flexibility become the default design principle of the system. Done right, the UK can lead globally in showing how AI makes clean energy not just possible but practical – turning climate ambition into lower bills, smoother operations and a transition people want to back.

Chapter 1

In the UK today, the power system is in transition, but much of its design still assumes a world of central power stations, one-way power flows and predictable demand. That legacy is colliding with something very different: a diffuse, fast-growing network of wind and solar as well as millions of assets at the edge – EVs, heat pumps, home batteries, rooftop PV – and a blurring of supply and demand as households can flex or even sell electricity back to the grid. More variability means far more coordination, with millions of timing-sensitive decisions across networks and markets. Delays in that coordination help drive higher costs. In 2024, the UK curtailed about 8.3 terawatt-hours (TWh) of wind, costing consumers between £390 million and 400 million,[_] and in 2024–25 the system operator spent about £2.7 billion balancing the grid, with constraints taking a large share.[_]

Markets and networks have not yet caught up with that shift. Many rules still reward the volume of energy generated more than when and how power is delivered. Information flows are also episodic rather than continuous, data sit in silos, and tariffs generally don’t reflect real-time cost or carbon – a legacy of the dispatchable era that makes less sense in a renewables-rich system. Flexibility – using demand, storage and distributed generation to adjust when power is consumed or supplied – can absorb cheaper renewables and relieve local stress,[_] but the infrastructure to deploy it quickly and reward it through predictable price signals and simple, auditable settlement between generators, suppliers and consumers is incomplete.

This points to a critical bottleneck: coordination friction, or the drag from fragmented data, inconsistent signals, and slow, patchy verification across markets and networks. This kind of friction blunts the use of flexibility, delays settlement and leaves operators working with partial visibility. The net effect is that flexibility goes under-used, curtailment lingers and savings reach people unevenly.

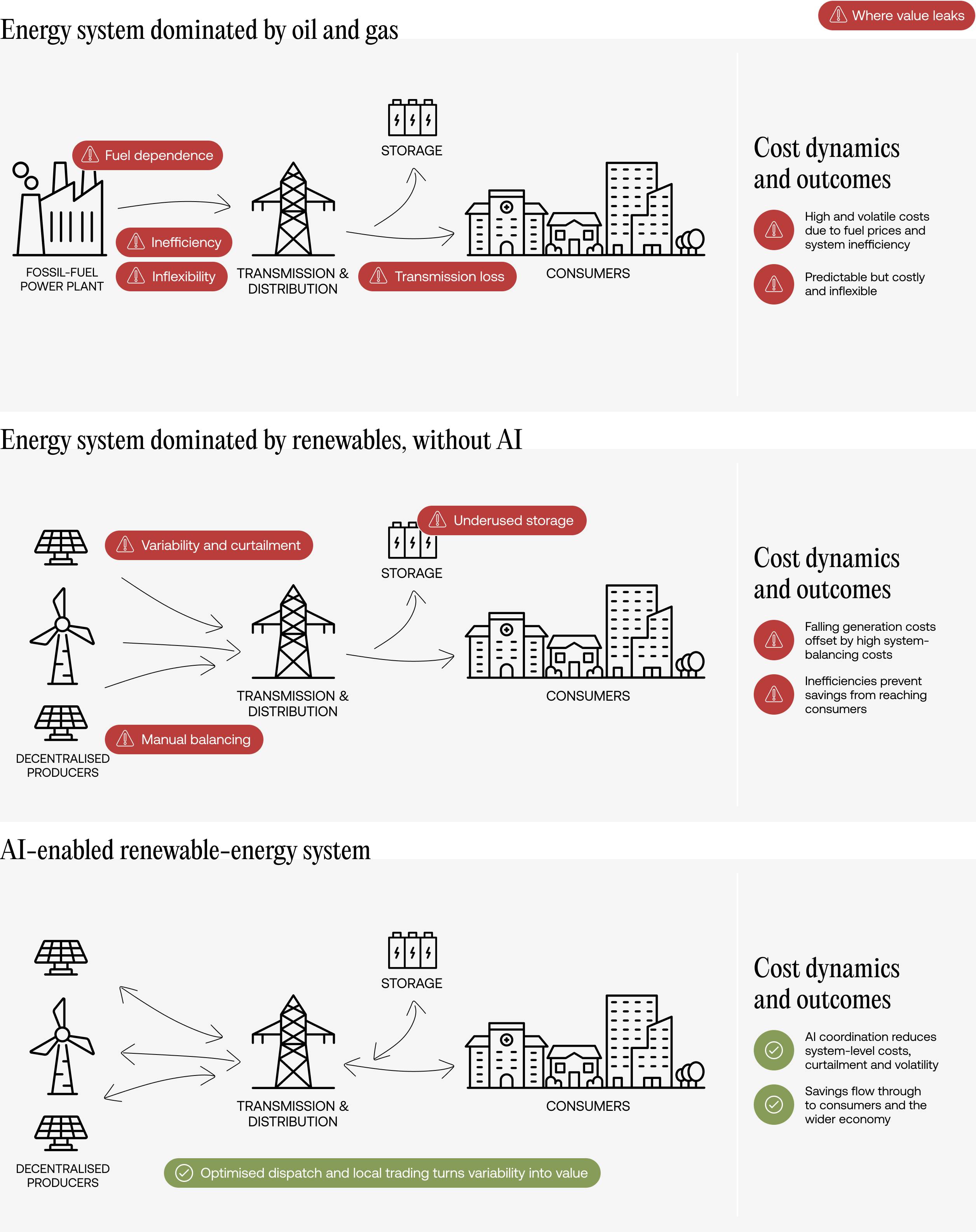

AI can help change this. It can act as the automation and optimisation layer for decarbonisation – not a replacement for infrastructure, but the intelligence that makes existing assets work harder and smarter, helping turn variability into value. While delivering cheaper electricity requires significant changes, as laid out in our recent paper Cheaper Power 2030, Net Zero 2050, AI has an important role in enabling that delivery. When used as an automation and optimisation tool by operators, suppliers, aggregators and even households (through smart devices and services), AI can:

Forecast and shift: anticipate supply, demand and constraints, then move flexible load and storage into cheaper, greener hours. This reduces curtailment, balancing costs and bill volatility.

Automate and verify: match homes, businesses and fleets to the right energy tariffs and services, and verify shifted kilowatt-hours automatically so credits arrive on time and without friction.

Target investment: use predictive modelling to defer or right-size reinforcement and accelerate connections, bringing clean generation onto the grid faster and reducing the costs passed to consumers.

Reduce soft costs and risk: automate applications (for grid connections, market participation and scheme enrolment among others), performance and compliance reporting, and dispute resolution; build reliable performance evidence so the risk level investors price in is lower, pushing costs down for everyone.

Maintain high reliability: apply predictive maintenance and faster fault detection to head off outages and reduce operational spend.

This marks a shift from using data to surface insights to using data to drive action. Intelligence becomes not just descriptive but operational, turning flexibility into an automatic function of the system.

AI can prevent value leaking out of the energy system

Source: TBI

With AI acting as an enabling coordination layer, a different future is possible. Smart energy tariffs become the default; appliances and cars auto-schedule when they draw power to optimise for price and availability of renewables; personal or business AI “energy agents” quietly optimise when and how power is used, drawing on live prices and grid signals to lower costs automatically; bills fall as use shifts to cheaper, greener hours without constant attention. Behind the scenes on the grid, millions of behind-the-meter devices respond automatically to system signals; models anticipate local stress and trigger demand response instead of relying on more expensive network upgrades or higher-cost power plants; and aggregated flexibility smooths peaks and absorbs oversupply. System costs fall, and with the right policy settings in place, savings can flow through to bills.

For the wider system, the logic also shifts. Markets begin to reward outcomes. Rather than being driven by fixed participation rules and administrative requirements, markets are geared towards how much demand was shifted, how quickly faults were spotted, how efficiently flexibility was used. While these outcomes already matter today, they are often hard to see or reward consistently. With better data and automation, they can become the primary basis for value. And government’s role tilts away from funding hardware on a project-by-project basis and towards building the market and digital conditions for coordination – in other words, trusted data access, standard application programming interfaces (APIs), continuous settlement and clear regulatory pathways for AI-enabled services to scale safely.

Put simply, today’s system is reactive, centralised and costly; an AI-enabled system is proactive, distributed and cost-efficient. In that future, the routine pieces – meters, data pipes, tariffs and regulation – form the backbone that enables clean power to be delivered more reliably and cheaply, sharing the savings fairly. AI doesn’t replace pylons or politics; it makes the system work for people.

AI in Practice: Project Better Energy x Joulen

Project Better Energy (PBE), the UK’s largest residential solar installer, has partnered with the startup Joulen to run an AI-driven optimisation platform that choreographs when homes and businesses generate, store and use power. Instead of panels, batteries and tariffs operating separately, the system coordinates them in real time – charging batteries when prices are low, drawing on solar when available and shifting demand away from peaks. PBE reports average household savings of around £1,100 a year, and business customers seeing energy costs fall by up to 47 per cent – including roughly £53,000 saved by a primary school and £54,000 at a manufacturing site.[_]

Chapter 2

The government cannot manage this transition with yesterday’s methods. The role of policy is not to pick winners technology by technology, but to create the conditions for AI to stitch them together into services that work for people. If the data, digital infrastructure, regulatory frameworks and market signals are aligned, AI can help make low-carbon living the default. To get there, government must rethink the market, regulatory, data and digital foundations so clean, consumer-facing services can flourish.

Rethinking Markets

If AI is to lower energy bills for households and businesses, electricity markets must be rewired so efficiency can flow through the system. This requires redefining incentives.

Today, savings that could be unlocked in any one layer of the energy system – for example, in distribution – are unable to reach the end consumer because wholesale, balancing and retail markets remain tied to old cost structures. Optimisation of how the system is run should be a design principle of market rules, not an incidental outcome, so reductions in system costs show up in bills. To help make this happen, DESNZ, supported by His Majesty’s Treasury (HMT) and DSIT, should set a joint strategic steer requiring Ofgem and NESO to embed flexibility, digitalisation and AI-enabled coordination.

Recommendation: Set a joint strategic steer across DESNZ, HMT and DSIT directing Ofgem and NESO to embed flexibility, digitalisation and AI-enabled coordination as core design objectives of market reform.

Delivering this shift in market design is crucial to unlocking the full potential of AI in the system. Without markets that reward timing and flexibility, the technologies able to provide it cannot scale. But the value flexibility could deliver if made central to market design is hard to capture because it is still treated as an add-on rather than a core market function. The UK has made progress (for example by piloting local flexibility and publishing a clean-flexibility roadmap[_]) but now needs to scale. NESO should lead work through the Electricity Market Reform programme to align the rules that determine who can take part in flexibility services and how their actions are measured, ensuring that those shifting demand or generation face coherent incentives, prices reflect real-time system value, and actions rewarded in one layer of the energy system are recognised across the rest. Designed this way, AI can help lower the cost of each unit of energy and those savings can reach consumers.

Recommendation: Align market layers so system savings flow through to consumers, with NESO leading work under the Electricity Market Reform programme to integrate flexibility participation and performance rules.

Markets should also reward measurable reductions in system cost, not just availability. When AI shifts demand or generation at the right moment, that value should be recognised automatically and settled transparently. To make that possible the UK needs shorter trading windows, open and interoperable data interfaces and updated market codes such as the Balancing and Settlement Code (BSC) and Retail Energy Code (REC), alongside distribution system operator (DSO) rulebooks. Ofgem’s ongoing work on Market-Wide Half-Hourly Settlement (MHHS) should be extended to ensure interoperability of data and verification standards, giving market participants a common foundation for automation and continuous settlement. These are not technical niceties but the machinery that makes efficiency measurable, tradable and visible on bills.

Recommendation: Extend Market-Wide Half-Hourly Settlement to include shared interoperability and verification standards, ensuring that automation and continuous settlement operate on a common foundation.

Running the power system itself also has to change. Instead of occasional, manual adjustments, the system should operate through a smarter process that uses real-time data to balance the grid continuously at the lowest cost. That means valuing actual performance, publishing simple measures of efficiency and acting on them. One useful metric is skip rates: how often a cheaper balancing action is passed over. Reporting this routinely would expose avoidable costs and build confidence that dispatch is genuinely merit-based.

At the local level, flexibility must be part of normal operations, rather than a patchwork of pilots. DSOs should be able to trigger and verify flexibility automatically when grid conditions demand it, using consistent contracts and measurement standards so participation is interoperable. Early initiatives like Megawatt Dispatch and the Local Constraint Market show what is possible. DESNZ and DSIT should ensure that the digital-spine initiative and related work through the Energy Networks Association converge into a single, interoperable interface for flexibility and constraint data, with Ofgem embedding its use in market and network codes and DSOs responsible for implementation. That would let AI optimise across local and national networks in real time, reduce duplication and curtailment, and lower network costs – benefits that should flow through to bills.

Settlement and retail also need to keep pace with automation. Half-hourly settlement is a milestone, not the endpoint; AI often acts within minutes. Government should complete MHHS as a foundation, then test sub-half-hour or event-based settlement where it clearly reduces costs, such as balancing or constraint management. The aim is not “five minutes everywhere”, but pricing and settlement that are timely enough for automation, accurate enough for investment and simple enough for consumers to see the benefit.

Finally, reform should be tested in the real world. A National AI Energy Sandbox, led by Ofgem, NESO and DESNZ, could trial new rules safely – allowing supervised AI participation with clear guardrails on transparency, auditability and consumer consent – and scale what works. Building on Ofgem’s existing Energy Regulation Sandbox it would allow supervised AI participation across wholesale, balancing, flexibility and retail markets under clear guardrails for transparency, auditability and consumer consent, enabling system-level testing of market design changes and scaling what works.

Recommendation: Establish a National AI Energy Sandbox led by Ofgem, NESO and DESNZ to test new market and regulatory rules safely, under clear guardrails for transparency, auditability and consumer consent.

Taken together, these are not tweaks. Without clear flexibility products, orchestration has nowhere to sell; without faster settlement, revenue certainty is lost; and without interoperable data and aligned incentives, efficiency gains get stuck. Put these foundations in place and the UK can build a system that learns, adapts and lowers bills in real time.

Modernising Regulation

If redesigning markets helps the system learn how to assign value, modernising regulation determines whether AI can actually deliver those savings to people. The shift is from prescriptive, process-based rules to outcomes-based, data-driven oversight. That transition has begun, but at a pace too slow for the change now needed. Regulation must evolve quickly enough to match the technology it governs. Instead of dictating how flexibility or AI services must operate, regulation should focus on whether they deliver the right outcomes. Ofgem should codify the targets of comfort, fairness, reliability and bill savings and publish a consistent measurement-and-verification framework so providers – whether human-run or AI-enabled – can prove results in a standardised, auditable way.[_]

Recommendation: Shift regulation from process-based oversight to outcomes-based assurance, directing Ofgem to judge success by comfort, fairness, reliability and verified savings rather than compliance with static rules.

Recommendation: Codify a single measurement and verification framework so suppliers, aggregators and AI-enabled platforms can prove performance consistently and transparently.

Ofgem is moving in this direction – from household and industrial demand to system-operator services – framing objectives around fairness, flexibility and reliability, and running an innovation sandbox (as mentioned above). Progress, however, remains cautious and fragmented. Much of the rulebook still reflects fixed tariffs and manual operations, which creates friction for AI – sometimes explicitly through conditions written for the UK’s legacy system, and sometimes inadvertently where it is unclear how rules apply to automation at speed and scale.

This is why the sandbox should become a standing, graduated pathway. With clear guardrails (such as explicit consent, comfort floors and overrides, audit trails and routes to redress) pilots can run safely at pace and reveal where rules genuinely need to change. Ofgem could adopt a “progressive licensing” model, where pilots that meet defined outcome tests automatically scale without restarting approvals. The sandbox should become a standing, always-open pathway, allowing projects that meet baseline guardrails – consent, transparency, reliability, data protection – to proceed under time-limited derogations. Used this way, the sandbox becomes a discovery engine for reform, not simply a venue for temporary exceptions. To give this staying power, Ofgem should embed the sandbox as a permanent regulatory function with dedicated resourcing and annual public reporting on learnings adopted into code or licence changes.

Recommendation: Create a standing regulatory sandbox with a progressive licensing pathway, allowing projects that meet consent, transparency and reliability guardrails to scale safely without restarting approvals.

As AI takes on more operational decisions – from forecasting and scheduling to automated dispatch – regulators will need a practical mechanism for certifying and supervising algorithmic participation. Building on Ofgem’s AI regulation laboratory, or “Reg Lab”, certification could focus on transparency, auditability, cyber-security and human oversight, ensuring that automation remains accountable without stifling innovation. DESNZ and DSIT should back the Reg Lab as the central coordination point for testing and assurance, linking it to national work on AI safety and governance so energy remains aligned with wider cross-government standards.

Recommendation: Strengthen Ofgem’s AI Reg Lab as the central coordination point for testing and certifying algorithmic participation, supported by DESNZ and DSIT.

Delivering this requires coordination. Ofgem should codify outcomes, set standards and formalise the pathway from pilot to business as usual. This should include clear timelines, tiered licensing and standing sandboxes for suppliers and aggregators, DSOs and NESO as flexibility buyers, and tech platforms coordinating EVs, heat pumps and storage. Market operators and the organisations that manage the rulebooks governing energy markets and networks should provide AI-ready test environments and be given a mandate to innovate, testing small rule changes under Ofgem oversight. To maintain coherence, DESNZ should convene a cross-regulator energy and data innovation forum bringing together Ofgem, DSIT and the ICO to align policy on AI governance, data standards and consumer protection. This coordination across government is crucial to ensure the regulatory system keeps pace with technology.

Recommendation: Convene an energy and data innovation forum bringing together Ofgem, DESNZ, DSIT and the Information Commissioner’s Office to align policy on AI governance, data standards and consumer protection.

The risk is not only that regulation lags; without deliberate design it can quietly stifle AI-enabled savings through inertia. The fix is to embrace experimentation, regulate based on outcomes, and treat discovery as part of the job, so AI can turn variability into value and make clean power cheaper and easier for people to adopt.

Building Data and Digital Infrastructure

AI can only optimise what it can see and control. To move from insight to action, government must treat data not as a reporting mechanism but as operational infrastructure through which AI can act on real-world conditions. When operational data are slow, patchy or locked away – and when the digital tools that put data to use are treated as short-term experiments – automation stalls.

While the UK already has millions of smart meters and connected devices emitting useful signals, the system still treats data and digital infrastructure as supporting acts rather than core to the system. The Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology has estimated that digitalisation-enabled flexibility could cut costs by up to £10 billion a year by 2050[_] – savings that depend on these coordination tools being built, maintained and governed as part of the system’s fabric.

There is broad consensus on what needs to change. As TBI’s Cheaper Power 2030, Net Zero 2050 argues, a smart, open energy-data environment with clear standards, trusted access and timely release is now a prerequisite for cheaper power. The next step is to move from insight to action. Today, data can show where flexibility would help, but the UK needs an AI-ready system that lets data trigger change automatically – shifting load, adjusting prices and coordinating devices the moment clean power is abundant. To make that possible, digital tools can’t sit alongside the system; they must become part of its operational core.

Regulators are beginning to take digital tools and those that allow flexibility more seriously. While RIIO-ED2’s DSO incentives[_] push networks to improve visibility of their systems, coordinate flexibility and use digital tools to manage local constraints, digital infrastructure still isn’t treated as being on par with physical reinforcement. Delivery remains uneven, with variable hosting-capacity maps, fragmented consumer-data access, scarce synthetic datasets for testing, and many coordination platforms or APIs relying on time-limited innovation pots rather than stable, regulated support. DESNZ, supported by DSIT and HMT, should now embed digital delivery into core network-planning and funding frameworks, making investment in data and software eligible under the same business-case rules as physical upgrades.

Becoming AI-ready means creating a data and digital backbone that is planned and funded with the same predictability as the physical grid. That means treating energy data as a first-order system asset that is specified, governed and published to shared standards. Priority operational data sets should use common schemas and identifiers, with NESO, DSOs and suppliers releasing them on consistent timetables and in machine-readable formats so optimisation services can operate seamlessly across regions. DESNZ and DSIT should use Ofgem’s forthcoming data and digitalisation strategy as the vehicle for this – setting mandatory publication standards and aligning incentives across DSOs to deliver them. A single, consent-managed route for household and small- and medium-sized enterprise data would give customers control and confidence, while high-fidelity synthetic data sets – artificial data sets that replicate the patterns of real energy data without revealing any individual customer information – could fill gaps where privacy or commercial limits prevent full release.

Recommendation: Treat energy data as core national infrastructure, embedding mandatory publication standards for priority data sets within Ofgem’s forthcoming data and digitalisation strategy.

Alongside trusted data, the UK needs a stable digital operating layer. Platforms that turn data into action – forecasting hubs, constraint and needs services, verification tools and asset registries – should have clear stewardship, predictable funding and open interfaces. Investment decisions should weigh digital solutions as seriously as physical upgrades, recognising where software can defer, right-size or better target network upgrades. DESNZ and DSIT should formalise and fund a long-term digital-infrastructure plan, building on the digital-spine prototypes, to turn current digital pilots into a nationally scaled backbone with enduring governance and investment. Public procurement can help standardise expectations by requiring interoperable, API-ready systems across the public estate.

Recommendation: Integrate investment in digital coordination tools into network funding frameworks, ensuring that software and data platforms are eligible under the same business-case rules as physical reinforcement.

Recommendation: Develop and fund a long-term digital infrastructure plan to turn pilot initiatives such as the “digital spine” into a nationally scaled, enduring backbone with clear stewardship and accountability.

Finally, an AI-ready power system needs a coordinated environment in which new digital and market tools can be tested safely before they go live. A national framework – linking representative data sets, standard APIs and simulated market and network rules – would let operators, suppliers and innovators trial tariff designs, congestion management and verification methods against realistic system conditions. Ofgem and DSIT could co-sponsor this test environment under the existing innovation sandbox and digital-spine initiatives, giving innovators a stable space to validate tools before market entry. This structure would give regulators confidence to scale what works without fragmenting innovation across one-off pilots.

Recommendation: Create a national test environment for AI-enabled energy systems, linking representative data sets, shared APIs and simulated market and network conditions so new tools can be validated before deployment.

Together, these steps would give the UK a coherent data and digital foundation – trusted, accessible and governed with the same discipline as its physical assets. That is what will allow AI to help cut curtailment and balancing costs, optimise for precise flexibility and bring visible savings to people’s bills.

Putting Households and Businesses at the Centre

The goal of these system reforms is not just efficiency, but visible, reliable savings for households and businesses so that AI can turn cleaner energy into lower bills automatically. However, today, many people who could participate in a cleaner, cheaper system don’t. The path from “interested” to “enrolled and saving” is splintered across grant portals, installer quotes, supplier switches and device set-up; people fall out long before they stand to save. Even when they do enrol, value can be uncertain. For example, because verification and settlement are slow or inconsistent, credits may arrive late or vary month to month. And in a large share of buildings the incentives don’t line up, as the decision-maker isn’t necessarily the bill-payer so viable upgrades can stall. The effect is that participation remains confined to early adopters and flexibility goes under-used.

AI can remove much of this friction – but only if policy clears the bottlenecks that stop it doing so. With consent and the right interfaces, AI can bring every step in the journey into one place, use meter and building data to size and configure solutions accurately, enrol the right tariff automatically, and verify delivered actions against half-hourly data so credits land predictably. This vision could soon include every household or business having a AI “energy agent” that quietly manages power on their behalf. With consent and clear safeguards, that digital assistant could learn a home’s routines, draw on live prices and grid signals, and decide when to charge, heat or store energy to keep costs low. The aim is to move from asking households to act on energy data to building systems that act for them automatically, safely and visibly.

That future is already starting to appear in early pilots and platforms. For example, the Open Energy initiative of Icebreaker One, a non-profit working to expand interoperable data-sharing, has piloted consent-managed frameworks that allow consumers to grant trusted access to their energy data across suppliers and services – an essential step towards a “single front door” for participation. Octopus Energy’s “Zero Bills” homes are bundling solar, batteries, heat pumps, tariffs and finance into one package, with optimisation handled in the background so the household experiences simplicity rather than complexity. And companies like Kaluza are beginning to automate verification by linking household-device data to suppliers, so flexibility actions are scheduled and settled directly on bills, making savings visible without extra admin.

The government’s role is to make these kinds of flows possible and reliable by setting the frameworks and standards that enable choice at scale. DESNZ and Ofgem should jointly design a consumer-participation framework that brings together existing schemes – from energy efficiency and smart tariffs to flexibility services – under a single set of interoperable data and measurement standards. That means establishing a common process for upgrades and enrolment, so accredited providers can manage eligibility, finance, installation and tariff selection end-to-end with consumer permission, not mandating a single route but making participation simple and consistent. Ofgem can underpin this through new licence conditions requiring suppliers and aggregators to support data portability and event-based settlement where relevant.

Recommendation: Design a joint consumer-participation framework led by DESNZ and Ofgem to bring energy-efficiency schemes, smart tariffs and flexibility services under one simple, interoperable set of standards.

It also means agreeing shared, event-based measurement rules and service levels for settlement, so when AI verifies a shifted kilowatt-hour, bill credits land quickly and consistently. Ofgem’s Market-Wide Half-Hourly Settlement reforms provide a starting point; these could evolve into a cross-industry service standard for credit verification and timing. It means making participation portable, so when a customer moves or switches supplier, their enrolment and entitlements follow the meter or registered asset automatically. DESNZ could coordinate this through the Smart Energy Code and retail-market review processes, aligning flexibility participation with existing consumer-protection frameworks.

Recommendation: Set common data and measurement rules so verified savings are credited automatically and on time, using half-hourly data as the baseline for event-based settlement.

And it means building trust and access. This can be done through approaches like licensing intermediaries with clear duties to act in the consumer’s interest, creating standard frameworks for landlord–tenant pass-through and requiring interoperability across devices so accredited services can coordinate them seamlessly. This should be done in partnership with DSIT and the ICO, ensuring that consent, privacy and data governance are handled consistently across energy and digital regulation.

Recommendation: Make participation portable across suppliers and addresses, ensuring that enrolment and entitlements move with the meter or registered asset when customers switch.

Do this, and AI can turn today’s fragmented, manual process into a simple service: configuration done once, optimisation happening quietly in the background, savings credited promptly, and participation that survives supplier and address changes. That is how consumer engagement scales, flexibility deepens and the system’s savings show up where people feel them – making clean energy the convenient, low-cost default.

If the past decade has been about proving that clean technologies work. The next is about making them add up for people – in a way that they can see on their bill. AI is the quiet tool that can do that – seeing across the system, coordinating in real time, and turning variability into value so clean power shows up as lower, steadier bills and fewer hassles. But that can only happen if the government lays the groundwork now with markets that reward timing and flexibility, regulation that assesses based on outcomes at the meter and on the bill, and data and digital infrastructure that are core to the system, rather than pilots. It will take the government leaning on Ofgem and NESO to move faster on flexibility and settlement reform, and joining up energy and digital policy so the rules, data and infrastructure work as one system. Do this and the UK can lead not just on climate ambition or AI research in isolation, but on using AI to deliver climate outcomes that people notice, value and support – at home and at work.