Climate action has reached a pivotal moment. While public support for climate action is at an all-time high, emissions are not decreasing at the pace the world needs.

Many countries in the Global North are stalling or falling short on their climate targets, while others are struggling to attract the finance required to reduce emissions. As of 2019, about $450 billion[_] of climate finance was deployed annually in countries in the Global South, roughly 20 per cent of what is needed by 2030. Announcements of cuts to foreign-aid budgets by countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany make finance flows to the Global South for climate action even more challenging.

These facts suggest that the world needs to scale up alternative solutions to complement existing action.

International carbon markets are a tool that all countries, in both the Global North and Global South, should seek to utilise. By creating a mechanism for countries to sell carbon credits to companies or governments in other countries in exchange for funds that are invested in domestic climate projects, international carbon markets enable the flow of capital for climate action from the Global North to the Global South. The benefits of these projects go beyond just the climate: they can also help to create jobs and strengthen infrastructure, supporting the development of local communities in the Global South.

Although it is already possible for countries to invest in cheaper emissions-reduction schemes elsewhere in the world and count these towards their domestic climate targets, few countries are fully harnessing the opportunity international carbon markets present. Part of the reason for this is that confidence in carbon markets has been undermined by concerns over their integrity and impact. However, new standards, rules and reforms along with the involvement of governments in shaping high-quality markets are beginning to address these issues, laying the foundations for renewed trust and the potential for large-scale participation.

Using carbon credits could reduce the overall cost of meeting all countries’ nationally determined contributions (NDCs) by more than half – or as much as $250 billion in 2030.[_] Expanding the use of international carbon markets could lower the cost of achieving global emissions targets. If the savings from implementation of NDCs using Article 6 markets were reinvested in increased ambition, emissions mitigation could be more than doubled.[_]

For many countries in the Global North, international carbon markets offer an opportunity to meet near-term climate targets at a lower cost. That means that for many jurisdictions, there is likely to be the potential to achieve more decarbonisation per dollar by funding a project in an emerging economy rather than by decarbonising only at home. This is because abatement options in countries in the Global South are generally more cost-effective than in countries in the Global North.

For example, studies show that the marginal abatement cost (the economic cost of an intervention that will reduce greenhouse-gas emissions by one unit, such as a tonne) of scaling renewables such as rooftop solar and offshore wind in Germany in 2030 could total around €200 ($220) per tonne of CO2 equivalent, whereas that same money could reduce significantly more emissions if used elsewhere, for instance to retire coal early in Indonesia, which some estimates show could cost as little as $12 to $13 to abate one tonne of CO2.[_],[_],[_]

Climate change is a global problem, requiring truly global solutions. If every government focuses only on addressing its own emissions, tackling climate change will cost more and take longer. Humanity cannot afford to let that happen. In many cases, it is possible to reduce a tonne of CO2 much more cost-effectively through deploying renewables and displacing fossil fuels in the Global South, where climate finance is lacking and energy demand growth soaring, than in decarbonising residual or hard-to-abate emissions in the Global North.

Although some countries in the Global North may be hesitant to invest in climate action outside their borders, well-designed and functioning international carbon markets provide an opportunity to support international development efforts while reducing emissions, and – if combined with industrial policy – could create further investment opportunities around the world. Scaling these markets now, by using them to meet a small proportion of domestic targets, would also help buy time to commercialise and scale the solutions the world will need to achieve net zero by 2050.

To bring carbon markets to their full potential, policymakers in both the Global North and Global South need to act now to ensure emissions reductions traded through these platforms are real and verifiable and to reduce political and logistical barriers affecting these markets. Investing in technological solutions and implementing policy changes in both “buyer” countries and “seller” countries could deliver the breakthrough for reducing emissions that the world is looking for.

Technology offers promising solutions to some of the challenges currently facing carbon markets. Governments can capitalise on the use of technology to support the foundations of carbon markets by:

Leveraging artificial-intelligence tools for climate and economic planning and to expand access to marginal abatement cost curves (MAC curves) for policymaking

Investing in digital monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) infrastructure using AI, satellite data and remote sensing

Supporting international collaboration on digital infrastructure, especially for smaller countries, through shared or multilateral registries

Embedding AI tools into regulatory processes to automate auditing, detect anomalies and improve oversight capacity

Encouraging the use and regulation of carbon-credit-rating agencies to independently assess offset quality and manage market risk with standardised, transparent methodologies

Policy mechanisms are also crucial to ensuring carbon markets can deliver on their promise. To harness the full potential of carbon markets, policymakers in predominantly Global North “buyer” countries should:

Provide a clear signal of market direction by implementing an advance market commitment for high-quality carbon removals

Provide clarity and confidence to the voluntary purchasers of credits by providing guidance, endorsing standards and aligning across international boundaries

In the medium term, allow a fixed percentage of international credits to be used by private companies to meet their domestic compliance obligations

Multilateral development banks and sovereign wealth funds should explore the potential to receive carbon credits as part of a broader return on financial investments

To attract investment for climate projects, policymakers in predominantly Global South “seller” countries should:

Clearly set out the path to meeting domestic NDCs and the role that carbon markets will play in helping to achieve economic and development goals

Strengthen domestic frameworks to engage with Article 6 and put in place the necessary policy, regulatory and legal frameworks

Empower finance ministries to collaborate on carbon market strategies

Strengthen South-South collaboration to share systems, knowledge and resources

Respond to demand from compliance markets that allow companies to use a fixed share of ITMOs to meet part of their obligations, and support the delivery of credits aligned with their standards

While developing both emissions reductions and removal projects in the immediate term, in the longer term, focus support on the removals market, to align with increasing global demand

Against a backdrop of economic uncertainty, slowing climate ambition and geopolitical tensions, supporting international carbon markets is more important than ever.

If the world gets this right, the prize is huge. Carbon markets could provide billions of dollars of capital to the Global South and bring down global emissions more cost effectively and quickly.

Chapter 1

The goal of carbon markets is to lower overall emissions in a cost-effective manner, by allowing reductions to occur wherever it is least expensive to do so. Carbon markets are trading systems that assign a monetary value to carbon emissions, enabling companies, governments and individuals to buy, sell or offset their emissions. By putting a price on emissions or proven carbon removals and allowing representative “credits” or “units” to be traded, carbon markets incentivise actors to reduce their emissions where the costs of doing so are less than the value of the emissions themselves.

There are three main types of carbon markets: compliance markets, voluntary markets and Article 6 markets.

The Emergence of Compliance Carbon Markets

To meet their binding Kyoto emissions targets in the face of rapidly increasing emissions, countries and states began to experiment with domestic emissions-trading schemes (ETSs). In 2002 the UK became the first government to introduce an economy-wide ETS, followed by the EU in 2005.

In an ETS, the government sets a limit, or “cap”, on the total amount of emissions allowed in a particular sector or area. For each tonne of CO2 emitted per year, firms under the scheme must buy and surrender to the government a credit (or unit), with the total number of credits capped in each sector. Units are tradable between emitters, allowing a low emitter to sell its spare units to a high emitter, creating a dynamic market price. Emissions reductions that would cost less per tonne than the price of units thus become the more economical option (either because the emitter doesn’t need to purchase units, or because they can sell surplus units at a price higher than the costs of their decarbonisation action). The cap on emissions is reduced over time, decreasing unit supply and driving up the value of units, thus incentivising further emissions reductions at rising price levels.

Carbon taxes, which directly price carbon emissions, emerged as a complementary approach to ETSs. These taxes charge businesses or individuals a fixed price per tonne of carbon dioxide emitted, or equivalent volumes of other greenhouse gases.

Today, governments in almost all countries in the Global North have implemented compliance schemes of some kind. These are domestic, mandatory schemes, created by regulatory bodies, which aim to help meet emissions-reduction targets.

The Rise of Voluntary Carbon Markets

Alongside compliance markets, voluntary carbon markets have also been developing. These markets function across international boundaries and are supported primarily by businesses that choose to offset their emissions.

In voluntary markets, credits (often referred to as “offsets”) are traded between developers who execute projects that reduce emissions and corporates who voluntarily purchase the resulting units to offset their emissions. These projects may be “removal” projects, which absorb greenhouse gases from the atmosphere – for instance through nature-based solutions or technology-based projects such as direct air capture – or reduction or avoidance schemes, whereby carbon credits represent reduced or avoided emissions – for example through not engaging in deforestation or scaling renewable energy.

In contrast to compliance markets, voluntary markets are typically not regulated by governments but have depended on the reputation of those administering the scheme. In some areas this has raised concerns over the robustness of attribution of credits to units of carbon removed or avoided.

The voluntary market has continued to develop since the late 2010s, and significant initiatives to raise the quality of voluntary carbon credits kicked off at COP26 in 2021. However, in the last few years increased scrutiny, particularly of overrepresentation of past carbon reductions, hit the value, supply and demand for credits in the voluntary market.

The Development of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement enables international carbon markets between governments and has several elements.

Article 6.2 allows countries to voluntarily cooperate in meeting their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) by buying and selling Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs, often called carbon credits). This allows countries to claim others’ emissions reductions towards their own climate targets by trading instruments that represent 1 tonne of CO2 removed from the atmosphere.

For example, Switzerland buys ITMOs from renewable-energy projects in Ghana. This helps Switzerland to reach its climate goals at lower cost while also supporting Ghana’s development. Countries must apply “corresponding adjustments” to their emissions inventories, meaning that when one country buys ITMOs from another country, the “buyer” country can subtract that emission reduction from its own emissions total, but the “seller” country must make a “corresponding adjustment” to ensure that the emissions reduction isn’t subtracted from its total. This avoids double counting emissions reductions.

Article 6.4, by contrast, creates a framework for a global carbon market rather than focusing on trades between two parties. Known as the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism, or PACM, this market allows countries to generate and trade carbon credits from emissions-reduction or removal projects. While Article 6.2 is decentralised and relies on bilateral agreements, Article 6.4 is centralised under a United Nations-led mechanism.

The key differences between compliance, voluntary and Article 6 carbon markets

Source: TBI analysis

The Current State of Play

Today, in part driven by increased climate ambition and regulation, as well as the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), compliance markets such as ETSs continue to expand in coverage and ambition throughout the world, and now cover 28 per cent of global emissions.[_]

The implementation of Article 6 is progressing, with cooperative agreements and pilot projects between countries beginning to emerge. The voluntary market is seeing increased oversight in response to concerns about the credibility and quality of credits. However, the impact that Article 6 will have on the voluntary market remains to be seen, with issuance of Article 6.4 credits expected to begin in late 2025. And despite growing momentum for Article 6.2, the pace of development needs to be accelerated.

Global action is needed to fulfil the promise of international carbon markets, enabling the flow of capital for climate action between countries, often from the Global North to the Global South. This paper sets out the actions that can help international carbon markets deliver, focusing predominantly on the opportunity to trade ITMOs under Article 6, as well as the voluntary market as a mechanism to facilitate the trade of voluntary credits internationally.

Chapter 2

There are three key reasons why now is the right time for governments to help scale international carbon markets. First, many countries are not on track to achieve their NDCs and are faced with the economic and political difficulties of “last-mile decarbonisation” within a given sector. Second, climate finance in the Global South is falling short of what is needed. Finally, just as the need for carbon markets is growing, markets themselves are developing, giving governments increasing opportunities to help scale them.

Efficient Use of Decarbonisation Dollars in the Global North

Carbon markets present a significant opportunity to reduce global emissions at an efficient price while still allowing individual countries to meet their NDCs.

Many countries in the Global North have already achieved the most cost-effective domestic decarbonisation actions within key sectors, while remaining attempts to decarbonise the last 5 to 10 per cent of the power sector, for example, or tackle hard-to-abate emissions in industry or agriculture, may be more expensive and harder to deliver.

The difficulty of domestic decarbonisation is apparent when looking at NDCs. Although targets to meet NDCs are fast approaching – in 2030 for most countries – many nations are not on track to meet them. Furthermore, most countries missed a UN deadline to submit 2035 NDCs, a delay that many attributed to economic pressures and political uncertainty.[_] The EU also delayed the release of its proposed 2040 target aiming for a 90 per cent reduction in emissions below 1990 levels due to concerns and pushback from some EU member states and political groups.

As NDC deadlines for both current and new targets loom, countries will need to consider the most cost-effective and pragmatic ways to achieve these. A “purist” approach, focused only on domestic delivery, will not necessarily achieve the best outcomes for the taxpayer or for tackling the climate crisis, especially if countries fail to deliver the decarbonisation promised. A more pragmatic approach, focused on scaling well-designed and high-integrity carbon markets and delivering even a small proportion of national targets through them, can help to reduce global emissions where it is most cost-effective in the short term, while buying time to develop and scale the necessary technologies needed to reach net zero by 2050. International carbon markets, as a supplement to domestic action, can offer a more economical option that also delivers sustainable development and innovation benefits in host (Global South) countries if structured in the right way.

Studies show that in 2030 the marginal abatement cost (the economic cost of an intervention that will reduce greenhouse-gas emissions by one unit) of scaling renewables such as rooftop solar and offshore wind in Germany could total around $220 per tonne of CO2 equivalent saved. In contrast, assessments indicate that same money could abate significantly greater emissions if used to retire coal early in Indonesia, with case studies showing the cost to be less than $50/tCO2e, and as low as $12 to $13/tCO2e by some estimates.[_],[_],[_],[_]

The cost of abating one tonne of emissions in countries in the Global North can pay for multiples more in countries in the Global South

Note: The price referenced here refers to the early retirement of coal plants, without the cost of replacing that installed capacity with renewables, grid improvements or battery storage.

Source: Misconel et al.; University of Maryland; Monetary Authority of Singapore and McKinsey & Company; Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis; TBI analysis

The economics and fiscal costs of climate action mean that some governments are now looking to capitalise on the opportunities that international carbon markets bring. In its April 2025 manifesto, Germany’s new coalition government pledged the use of Article 6 credits in its climate policy, allowing up to 3 per cent of Germany’s emissions-reduction target to be met through foreign carbon reductions. The EU Commission has proposed a plan to allow the use of international carbon credits for up to 3 per cent of the EU’s 2040 emissions-reduction target, meaning it could buy credits in the final four years running up to 2040. While the proposal (at the time of writing) still requires parliamentary and EU Council approval, in theory it would bring some 150 million tonnes of additional demand for carbon credits.[_]

However, other governments are concerned that by investing in international carbon markets to achieve their NDCs they are foregoing investment in climate action domestically, and therefore may lose potential innovation, green jobs and growth opportunities such investment may deliver. While interventions to reduce emissions domestically may stimulate local economies (and therefore might be preferred by voters), the electorate won’t directly see the benefits of investment in climate action overseas.

While international carbon markets can play a significant role in reducing global emissions, they should not be seen as a substitute for domestic decarbonisation. For all countries, domestic decarbonisation should be the primary focus. However, the use of international markets offers a cost-effective complement to domestic action which brings benefits in addition to the immediate climate benefit.

Sufficient Capital for Climate Action in the Global South

As countries in the Global South grow and their energy needs increase, they are expected to account for a larger share of global emissions in the future. This means scaling climate solutions in countries in the Global South is a critical part of limiting global temperature rises.

However, current investment needs for climate projects in countries in the Global South far exceed existing available resources. As of 2019, about $450 billion[_] of climate finance was deployed annually in countries in the Global South, roughly 20 per cent of what is needed by 2030.

Traditional aid budgets are also shrinking in key donor countries such as the US, UK and Germany, which will likely leave a gap in funding for climate-related projects and initiatives.

Carbon markets can help deliver funding that supports sustainable development in countries in the Global South and provides additional resources to implement climate projects. Several countries in the Global South are exploring how they can attract finance through harnessing international carbon markets.

Maturing Markets

Just as the need for, and value of, international carbon markets become clearer, markets themselves are about to become more significant.

The rules for Article 6 of the Paris Agreement were finalised and formally launched in Baku in November 2024. This mechanism, enabling bilateral (Article 6.2) and multilateral (Article 6.4) exchanges of ITMOs, has the potential to help countries in the Global North achieve their climate targets more economically, while also promising to provide sustainable development financing for countries in the Global South. With Article 6.2 agreements underway, and Article 6.4 standards soon to be finalised, it is essential that governments understand and apply carbon-market mechanisms within their own contexts.

Chapter 3

Despite years of international negotiations and significant investments, carbon markets are yet to achieve their full potential. In part this is due to perceived political difficulties of using these markets.

A fundamental concern for governments is the potential for domestic political backlash arising from the perception of “outsourcing” climate action to other countries – and sending the capital to fund it abroad. Although it is currently possible for countries to count climate action abroad towards their domestic NDCs, exporting emissions reductions can be perceived as undermining domestic co-benefits and growth opportunities that could arise if that money was invested at home. In addition, countries need to weigh up whether relying on units to meet near-term targets could make it harder to achieve future NDCs. Under the Paris Agreement, countries are required to submit NDCs every five years, with each one more ambitious than the last. Delaying domestic emissions reductions could leave a steeper mitigation curve later. However, the use of only a small proportion of international units mitigates much of this risk while also allowing for near-term action at a lower cost, something that the current political environment, together with the urgency of addressing the climate crisis, makes a priority.

In addition, technical challenges need to be addressed by governments on both the demand and supply sides of carbon markets. On the demand side, there are barriers preventing governments and companies in the Global North from purchasing carbon credits from abroad. On the supply side, there are barriers hindering governments in the Global South from developing effective climate projects that can generate tradable credits.

Barriers to scaling international carbon markets

Source: TBI analysis

Demand-Side Barriers

Although carbon trading between governments is on the rise – to date there have been approximately 97 bilateral agreements between countries under Article 6.2[_] involving 59 countries that have or intend to sell or buy ITMOs – most agreements are currently for very small volumes of emissions reductions. And while a number of countries have expressed an intention to purchase ITMOs, not many have taken concrete steps. For example, the UK does not currently have plans to use ITMOs to meet its climate targets under the Paris Agreement, with the Climate Change Committee explicitly recommending against their use, except possibly for international direct air carbon capture funding closer to 2050.[_] In addition, demand in voluntary markets has remained relatively flat over the past few years.

While there is potential for demand to increase, several barriers currently stand in the way. Some of the key barriers and solutions are summarised in Figure 4.

Demand-side barriers and solutions

Source: TBI analysis

Supply-Side Barriers

To date, many countries in the Global South have failed to attract finance through carbon markets. Since 2020, the voluntary market has been the primary credit market for low-income countries, with credits generated mostly from nature-based solutions.[_] Six low-income countries account for more than 75 per cent of all voluntary market credits – Cambodia, DRC, Bangladesh, Uganda, Malawi and Zambia.[_]

There are several barriers that prevent the credible supply of climate projects, or the involvement of countries in the Global South in Article 6 markets. These barriers, and corresponding solutions, are set out in Figure 5.

Supply-side barriers and solutions

Source: TBI analysis

Chapter 4

Governments need to take steps to overcome the barriers that are currently preventing carbon markets from scaling. They can do so by harnessing technology, which is developing rapidly, as well as implementing policy solutions to address barriers on both the demand and supply side. The following sections set out solutions across three areas over the short and medium term.

Recommendations to empower international carbon markets

Source: TBI analysis

Policy Recommendations for Technology Adoption

As outlined, integrity concerns are holding back carbon markets. Purchasers need assurance that the credits they purchase are high-quality, credible and transparent.

Common integrity concerns in carbon markets

Source: TBI analysis

MRV is essential for proving that a project has reduced or removed greenhouse-gas emissions. Traditional MRV involves collecting data on a project’s baseline emissions, measuring the actual emissions and calculating the carbon reduction achieved. Project developers, carbon-credit byers and regulatory bodies all rely on MRV data. However, traditional MRV is often very expensive due to factors like manual data collection and the complexity of verifying large volumes of data.

A new wave of technologies can help bring integrity to international carbon markets. These should stimulate demand for carbon credits, benefitting countries in the Global South that might be selling these credits. Technologies can help address issues all along the pipeline from project development to credit issuance and trading.

New technologies can help track projects throughout their development

Source: TBI analysis

Recommendation: Leverage AI tools for climate and economic planning and to expand access to MAC curves for policymaking.

In the Global North, MAC curves are a routine tool of climate economics. In many countries in the Global South, however, this technical and econometric tool is out of reach: reliable emission baselines are patchy, cost data is held by corporates and modelling software comes with significant licence fees. As a result, economic plans, NDCs and Article 6 strategies are often developed without this vital information.

Yet these tools are essential for identifying the most cost-effective emissions-reduction opportunities across different sectors. In the absence of detailed local data and modelling capacity, AI offers a transformative opportunity. AI systems can rapidly aggregate and analyse diverse data sources – from satellite imagery and emissions inventories to economic and infrastructure datasets. This fills critical gaps and producing more granular, actionable MAC curves than traditional methods allow.

In the past, free modelling tools typically meant Excel macros that were technical to edit or update. Today policymakers can use these existing Excel workbooks, like the MACTool from the Global Climate Action Partnership[_] or the ggmacc package[_] paired with an AI-empowered cloud notebook like Google Colab or Deepnote. A policymaker can then type, “show me the cheapest path to cut 15 megatonnes (Mt) CO2 by 2030”. The large-language model then can draft the code, and the policymaker can watch the waterfall chart materialise within seconds. Because each assumption for the model is visible line by line, the relevant analyst can then review or update the model easily.

For systemic questions and analysis, these data sets can slot neatly into open-source tools like OSeMOSYS or TransitionZero’s Scenario Builder, two open-source energy modelling systems.[_],[_] Where that is too computationally heavy, researchers could even call upon emIAM, an emulator for integrated assessment models trained on ten existing models, that can reproduce economy-wide MAC curves in milliseconds on a laptop.[_] Such tools mean that ministries no longer need to commission bespoke models or hire consultant companies to test whether new climate policies make financial sense.

With the right digital infrastructure and governance in place, AI-enabled MAC curves can support countries in aligning their development and climate ambitions, while also attracting investment by demonstrating clear, data-driven decarbonisation pathways.

Recommendation: Governments should set the standards to attract investment in digital MRV infrastructure using AI, satellite data and remote sensing.

One of the biggest integrity challenges in carbon markets is accurately measuring emissions reductions or removals. Many carbon projects suffer from flawed baselines against which to measure change (for instance overly optimistic or pessimistic assumptions about deforestation risk), unverifiable or outdated data, and project developers relying on assumptions rather than empirical observation.

Satellite imagery and AI-powered remote sensing can help monitor and verify emissions reductions and compare these to a baseline of activity that would have occurred without intervention, particularly in areas like forestry and land-use changes. They can track land-use changes and deforestation, flag potential risks like fire or droughts, and monitor vegetation health. Advanced sensors can now measure biomass at the tree level, to provide much more precise carbon-stock estimates.

Companies like Pachama and Kayrros use machine learning to monitor forest growth and land-use changes with precision, while LiDAR (3D scanning) drones can measure biomass and forest growth, allowing for highly accurate carbon-stock estimates. Climate TRACE, an independent global coalition co‑founded by Al Gore, leverages satellite and remote‑sensing data with machine learning to generate near‑real‑time, facility‑level emissions estimates for more than 660 million sources worldwide. AI-powered models can also predict how much carbon a project can capture, making planning and risk assessment more reliable.

The EU’s approach to data sharing should serve as an example: in addition to using its Copernicus satellite data to power its certification framework for permanent removals (the Carbon Removal and Carbon Farming Regulation or CRCF), it has also applied a “full, free, and open” policy to these data since 2013. This enabled companies like Kayrros to commercialise the data. These two policies are additive and innovative: open data provides credible, low-cost evidence while the CRCF channels that evidence into a trusted and regulation-backed market mechanism – creating a virtuous cycle that accelerates uptake, empowers transparency and operationalises capital flows for removals.

Recommendation: Support international collaboration on digital infrastructure such as blockchain, including through shared or multilateral registries.

Registries are systems that record emissions reductions and where carbon-credit transactions can take place. They track who owns carbon credits, when they were issued and whether they’ve been retired. This is important as it can help prevent double counting and fraud. However, fragmented data across multiple registries and standards has been a longstanding issue for carbon markets and has led to a lack of market trust. Not all countries – especially small countries – need their own registry. Instead, regional or multilateral registries (like Article 6.4) can help reduce administrative burden and data discrepancies.

Blockchain can improve carbon-market registries. Recording every carbon-credit issuance, transfer and retirement on a blockchain ledger, which cannot be tampered with, would prevent double counting and fraud, as well as ensuring all data are consistent and up to date. Smart contracts could offer further efficiencies: automating and enforcing the rules governing credit issuance and retirement, reducing administrative overhead, automating transactions and minimising the risk of human error or manipulation.

The World Bank-backed Climate Action Data (CAD) Trust, launched at COP27, uses blockchain-powered digital infrastructure to tie together private, national and international registries in a trustworthy, decentralised model, improving transparency of data. This offers a fully traceable record of carbon-credit activities, including issuance, trading and retirement, which should enhance trust and security in the carbon trading process. Zimbabwe recently launched a blockchain-backed carbon-credit registry which is designed to bring transparency and accountability to its carbon market. Ghana has also signed up with ZERO13 (a fintech platform) to connect its national Ghana Carbon Registry to the blockchain-based Global ITMO Trading Hub and Settlement Network in Singapore. By embedding and automating accountability and traceability into the trading infrastructure itself, blockchain has the potential to become a foundational layer of carbon markets, one that is enhanced by its use across jurisdictions.

Recommendation: Embed AI tools into processes to improve the monitoring and regulation of carbon markets, including to automate auditing, detect anomalies and improve oversight capacity.

Beyond improving technical integrity, AI can substantially reduce the administrative workload of monitoring and regulating carbon markets. While a traditional manual audit can process 100-150 projects per year, a digital MRV system, backed up with AI, empowers a single auditor to verify 10 projects per day.[_] This reduces timelines from months to days and frees up staff to concentrate on high-risk cases and policy design. Natural-language-processing tools can extract key details from documentation and flag inconsistencies or flawed baselines, while anomaly-detection models can reconcile emissions data from across registries, slashing the burden of data entry, cross-checking and error resolution.

Recommendation: Encourage the use and regulation of carbon-credit-rating agencies.

A new generation of companies called carbon-credit-rating agencies assess the risks of credits with frameworks like those used in financial risk assessment. Using letter-grade ratings, like their bond-market counterparts, companies like BeZero and Sylvera aim to capture data covering all potential points of failure in a project. To do this at scale and with high degrees of accuracy, these firms employ tech-heavy assessment methodologies that combine remote sensing, machine learning on satellite and LiDAR data, remote hazard detection, and other domain expertise. The trustworthiness and validity of these agencies’ work is dependent on strong conflict-of-interest management, transparent ratings methodologies, and high technical standards. Governments should actively explore the regulation of these agencies, similar to their debt-market counterparts.

Policy Recommendations to Fix Demand-Side Barriers

Stimulating greater demand for international carbon credits will be essential to help carbon markets meet their full potential. However, currently there aren’t sufficient incentives in place to stimulate demand at the scale that is needed. As set out above, in addition to integrity concerns, many countries are hesitant to participate in carbon markets either because of a lack of knowledge about cost savings, a lack of certainty over Article 6 rules or fear about losing domestic growth opportunities as a consequence of investing overseas rather than in domestic decarbonisation.

In addition to addressing integrity concerns, there are steps governments in the Global North can take to stimulate demand and finance emissions reductions in the Global South.

Short Term

Recommendation: Provide a signal of market direction by implementing an advance market commitment (AMC) for high-quality carbon removals.

Carbon-dioxide removals (CDR), ranging from engineered solutions like direct air capture to afforestation, will play a vital role in the journey to net zero. Yet today, the market signal for durable CDRs remains weak. Article 6 has so far struggled to deliver predictable demand signals, or clear agreement on project selection for high-quality credits. If unchecked, it risks becoming a platform for lowest-common-denominator offsets, like its predecessor, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM).

A targeted AMC could change this. By committing future demand for high-quality carbon removals, a coalition of governments could both de-risk private investment for CDRs and push the Article 6 supervisory body (SBM) to prioritise corresponding adjustment and rigorous methodologies, increasing perceptions of market integrity.

The EU and its members, alongside the UK, Japan, Singapore, Switzerland and South Korea, are well-positioned to lead. Each has demonstrated the political will to invest in removals already, and Japan in particular is already beginning to allow companies to meet their ETS obligations with limited use of international removal credits.[_] The EU is signalling it will allow the same, and the UK has indicated the introduction of a similar policy, but only domestically.[_],[_] A coordinated AMC from this group, underpinned by shared standards on quality and aligned on international climate coordination, would offer the scale and coherence needed to move markets. This coalition could also leverage strategic diplomacy to encourage uptake in key host countries.

Momentum is building, and these countries should follow the lead from existing AMCs: the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has pledged to buy $450 million of African carbon credits by 2030, and Saudi Arabia has signed a deal to purchase 30 million tonnes of credits from the Global South by 2030.[_],[_] Their efforts underscore a growing geopolitical awareness of carbon markets as economic tools and soft-power instruments. European and East Asian governments should join them and take a competitive step further by committing to an AMC for removals.

Countries in the Global North should launch a coordinated AMC by COP30, grounded in a shared commitment to environmental integrity, innovation and global cooperation. By aligning on high quality standards and pooling demand, this coalition could accelerate investment in removals, reshape host country incentives and bring credibility back to the centre of Article 6.

Recommendation: Provide clarity and confidence to the voluntary purchasers of credits by publishing guidance, endorsing standards and aligning across international boundaries.

Hundreds of companies have pledged to hit net zero by 2050, yet the voluntary carbon market is still under-regulated, under-trusted and under-scaled. This means that demand for voluntary credits is stagnating, leaving an untapped source of capital. Governments in the Global North should create clarity and confidence for corporate buyers, to help stimulate demand. To combat doubts over the credibility of carbon credits, governments should endorse robust, science-based crediting methodologies such as the Core Carbon Principles (CCP) from the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market, as the UK and France have recently done. In line with recent guidance from the Voluntary Carbon Market Integrity Initiative, governments should signal that carbon credits should comprise only one part of a company’s decarbonisation strategy – and be transparently reported as such. They should be used to offset residual and supply-chain emission targets, rather than disrupt genuine direct decarbonisation. Finally, instead of pursuing separate regulatory frameworks independently, countries should collaborate on a clear and uniform approach across jurisdictions to avoid confusing corporations that operate across international borders, a step that the UK, Singapore and Kenya have recently begun.[_]

Medium Term

Recommendation: Consider allowing a fixed percentage of international credits to be used to meet domestic compliance obligations.

A growing number of governments are enabling companies that are regulated under compliance markets (such as an ETS or carbon tax) to use a limited number of high-quality carbon credits, domestic or international, to meet their compliance obligations. As of the first half of 2025, 40 per cent of compliance markets do this.[_] While domestic credits reinvest funds into a nation’s own natural capital, limited international credit (ITMO) use could deliver the same impact at a lower cost. Measures to require the buyer country’s own involvement in, or even ownership of, the projects in Global South countries that generate credits could help mitigate concerns that such proposals don’t support economies at home.

ITMO use in compliance markets, using the example of a carbon tax

Source:TBI

If implemented in the right way, allowing ITMO use in compliance carbon markets could reduce costs for domestic businesses, as well as spurring demand for high-quality climate projects and channelling finance to mitigation efforts in countries in the Global South.

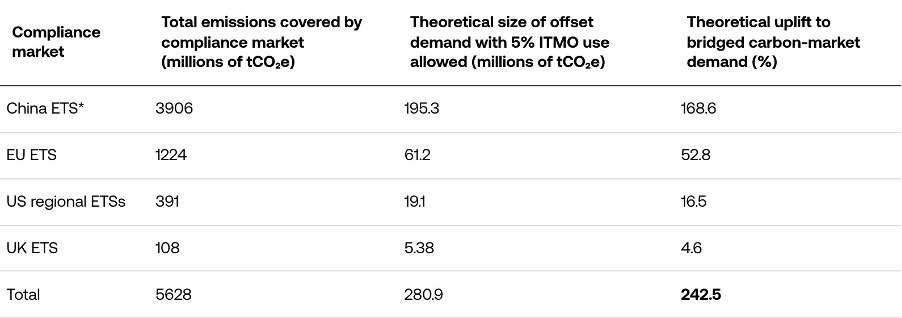

This approach could also help to address the long-term demand issues in international carbon markets. As shown in Figure 10, allowing companies to use eligible carbon credits to offset a portion of their emissions could provide a steady and sustained stream of demand, potentially on the order of hundreds of millions of tonnes.

The potential demand increases to carbon markets if additional compliance schemes were to allow 5 per cent use of ITMOs in compliance markets

Source: World Bank Carbon Pricing Dashboard, country-level emissions data, TBI analysis.

* China’s National ETS already has a mechanism for offset usage, allowing 5 per cent of carbon emissions to be offset, but only with domestic projects.

Methodological note: The uplift to demand is calculated by taking the maximum potential demand from existing compliance carbon markets that allow offset use (115.9 MtCO2, detailed in the supply-side recommendations below) and calculating the individual added demand if the above markets also implemented offset use.

Several governments have already implemented this approach, albeit with key differences. Singapore has a carbon tax on greenhouse-gas emissions that applies to facilities emitting above a certain threshold. Businesses can reduce the amount they pay in carbon tax by using international carbon credits, but only for up to 5 per cent of their emissions. When businesses buy credits, they are in effect paying for Singapore’s participation in international carbon markets. This adds flexibility for businesses and helps Singapore meet climate goals through cost-effective international cooperation.

How Singapore uses ITMOs within its compliance market

Source: TBI analysis

In Switzerland, revenue from taxing motor-fuel importers is channelled to a not-for-profit organisation with a public mandate to help meet Switzerland’s climate goals. The KliK Foundation is mandated to purchase ITMO offsets, predominantly from abroad, on the state’s behalf, thereby facilitating a quarter of the country’s NDC commitments.

South Korea’s ETS similarly allows companies to meet up to 5 per cent of their obligations using international credits from projects Korean firms have helped develop. This ensures Korean businesses are involved in the supply chain, such as providing technology for MRV or financing the project. This means that even though emissions reductions occur overseas, there is still some benefit for Korean firms, which can help to overcome public backlash or fears that taxpayers are subsidising other countries.

This approach has several advantages. Regulatory endorsement of international carbon markets – whether voluntary or under Article 6 – creates stable, predictable demand for credits. Allowing entities to offset a small percentage of their emissions with offset credits, typically less than 10 per cent, can gently ease the existing financial and economic costs of carbon levies to emitters and to the economy at large, especially when domestic abatement options are expensive.

However, there are some risks. Done poorly, allowing ITMO use to meet compliance obligations could dilute the incentives for companies to decarbonise, allowing them to buy more cost-effective offsets abroad instead of reducing their own emissions. Timing is important too: buying ITMOs for 2035 NDC targets means that a government will have to purchase even more ITMOs (or make deeper cuts) to stay on track for its subsequent NDC. This means these schemes need to be designed carefully, with strict credit quality, robust governance and clear limits. To mitigate this, countries should adopt strict caps on credit use, typically between 4 per cent and 10 per cent.

Another key challenge is that governments would also forgo the same 5 per cent of revenue from their compliance markets. However, in return, they lower compliance costs for businesses and achieve climate action at a lower cost.

Furthermore, concerns over the variable quality and credibility of voluntary credits means there must be stringent approval processes. Solutions include rigorous third-party verification or direct governmental oversight. Administrative complexities and potential political backlash, stemming from reduced domestic revenues or international financial flows, also require careful management. Countries can navigate these challenges by optimising the balance between domestic and international offsets, emphasising local co-benefits and maintaining transparency with stakeholders.

Policy mechanisms to allow ITMO use in compliance carbon markets vary significantly, reflecting national contexts and institutional capacities. Options range from direct acceptance of existing voluntary-carbon-market standards, as Singapore does, to more controlled approaches such as South Korea’s, which requires project-specific government approval. Switzerland exemplifies a single-registry approach, channelling carbon-tax revenues through a dedicated entity tasked with offset purchases, simplifying administration and ensuring consistent credit quality.

Policy options for mechanisms assessing credit integrity, when allowing ITMO use in compliance carbon markets

Source: TBI analysis

Countries could consider mandating the involvement of domestic businesses in projects in host countries to harness the shared benefits of this finance flowing to the Global South. South Korea and Japan have already demonstrated this. South Korea requires Korean project developers to run the international projects accepted into their scheme, while Japan requires Japanese controlling (greater than 51 per cent) ownership of or investment in the offset project itself. In practice this means that a Japanese company must either co-fund the project, supply technology and expertise, cover operations and maintenance, or act as a joint venture partner. These measures help these countries strike a more strategic balance than their peers.

Singapore and Switzerland, as small countries with limited project opportunities at home, now focus on international supply. Countries with abundant natural resources like China and Colombia mandate exclusive domestic credit origins. Policymakers could require the involvement of their own businesses in projects abroad. This would protect political interests at home while financing decarbonisation abroad, where it’s more cost effective.

Policy options to balance international and domestic offsets

Source: TBI analysis

Recommendation: Multilateral development banks (MDBs) and sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) should explore the potential to receive carbon credits as part of their return on investment.

MDBs, a key source of financing for the Global South, and SWFs, another source of capital from the Global North and Middle East, can fill the missing link between existing green project finance and further scale for international carbon markets.

ITMOs in MDB Investments

Considering the potential of ITMOs in their investments – both concessional and commercial – could help strengthen the case for existing investments made by MDBs. These investors would be incentivised not just by the existing business-as-usual yield, but by the option to receive some of the emissions reductions generated as part of their investment return as ITMOs. These could then be sold or redistributed to their donor governments (in MDBs) or the home governments (in SWFs).

These investments could be structured in such a way to satisfy donors wary of existing Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development rules on official development assistance (ODA), which prohibits the use of ODA funds for direct benefit to the donor country. Despite ITMO-linked returns being funded by non-ODA instruments they could still help deliver on development goals.

ITMOs in SWF Green Debt Investments

SWFs, particularly those with climate mandates like Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global or Norges Bank Investment Management, Singapore’s GIC and the UAE’s Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, could explore green instruments that yield ITMOs. By backing MDB-originated green bonds or loans that embed access to ITMO flows, they could gain exposure not just to coupon payments, but to a new class of mitigation assets with some ITMOs baked into payment structures. These investors could then monetise these credits to sell to others, transfer them to their host governments or donors, or simply cancel them as a reputational hedge.

Integrating ITMO transfers into debt-restructuring deals, especially debt-for-nature (DFN) swaps, also provides innovative new sources of revenue into such deals. While DFN swaps reduce debt burdens on the basis that new fiscal space is used to finance conservation or other climate projects, ITMO revenues could either be used to further reduce the debt burden, or act as an instrument of new fiscal space to dedicate to new, monitored uses.

Pilot to Market

Early actions in this vein are already underway. The World Bank’s Transformative Carbon Asset facility and its successor, Scaling Climate Action by Lowering Emissions (SCALE), aims to deliver carbon credits (and ITMOs) to donors via results-based finance. The Asian Development Bank too, has the Climate Action Catalyst Fund, providing upfront financing to climate action that will later generate carbon credits that will be returned to Fund contributors. Switzerland’s Klik Foundation, the Norwegian Global Emission Reduction (NOGER) Initiative, and the Swedish Energy Agency are well placed to take advantage of these structures, having signed multiple Article 6 agreements and been early buyers of ITMOs.

But for this to scale, more pilot projects and standardisation will be needed. Registry linkages, legal templates and sample projects to set precedents will drive this asset class forward.

Exploring the Impact of ITMOs in the EU ETS

Allowing some volume of international units to be used to meet domestic compliance obligations could be appropriate for all Global North compliance schemes, but particularly in the world’s leading and most credible emissions-trading scheme: the EU’s. Facing fiscal and political pressure to loosen its 2040 carbon neutrality target, the EU should consider this approach. If the bloc addresses key challenges, namely using a cap on offset use, strictly monitoring the eligible methodologies and requiring a share of European project-developer involvement, it could position its project developers as an exported service industry while also allowing for equitable ownership with local communities. Doing so would not only finance cost-effective abatement opportunities, but it could also boost relations with the low- and middle-income countries impacted by its carbon-border tariff and deforestation regulation, helping to finance the conservation of their forests and renewable-energy development.

The EU ETS has worked wonders at driving out coal and incentivising the rollout of renewables, yet as it expands to transport and buildings, member countries are increasingly asking for breathing room. As cheaper abatement options are implemented, the marginal cost of the remaining abatement rises, together with the ETS price. Germany, France, Sweden, Poland and the Netherlands are among the member states investigating and supporting proposals to allow Article 6 credits to contribute to the EU’s climate target of reducing emissions by 90 per cent by 2040 (relative to 1990).[_]

We built an indicative model[_] to demonstrate the effect of allowing ITMOs into the EU ETS on ETS prices from 2025 to 2050. Our indicative model shows allowing companies to meet up to 5 per cent of their ETS obligations through ITMO use could achieve the same abatement at 15.1 per cent lower overall cost for EU businesses, as the ETS price is trimmed roughly 12 per cent throughout the 2030s and 2040s, while still maintaining the price signal of the ETS.

Cost savings of 5 per cent ITMO use in the EU ETS

Source: TBI analysis

With a 3 per cent cap on the use of ITMOs in the EU ETS, as proposed by the new German coalition government, cumulative compliance costs would fall by €187 billion ($218 billion) to 2050, a 9.2 per cent discount on the status quo. With a 10 per cent cap, savings reach almost €600 billion ($698 billion). Reduce it to 1 per cent and savings shrink to €63 billion ($73 billion).

The cumulative savings and risk-adjusted net benefit of allowing ITMO use in the EU ETS

Source: TBI analysis

The risk-adjusted net benefit shows when savings from allowing ITMO use are still worth more than the risk of blunting the ETS’s main job of being a price signal for decarbonisation (and the impact of this lower price on decarbonisation in subsequent carbon budgets). The sweet spot in this case, judged by the risk-adjusted net-benefit curve, ETS price signal and political palatability, lies in the middle at 5 per cent.

Cumulative savings and risk-adjusted net benefit of allowing ITMO use in the EU ETS

*Net benefit: gross savings minus squared-risk penalty; penalty coefficient set so that a 25 per cent price cut would wipe out the entire gain.

Source: TBI analysis

Allowing ITMO use in the EU ETS isn’t necessarily a one-way flow of cash to the Global South. The EU, and any other government considering allowing ITMO use in their compliance markets, could insist that firms using this mechanism hold at least 20 per cent equity in approved mitigation projects. Even that modest slice would channel an estimated €4 billion ($4.7 billion) to €5 billion ($5.8 billion) a year in export revenues to EU suppliers of renewables and its equipment, digital MRV, satellite analytics and carbon-removal kit by the early 2030s. The policy would therefore complement the bloc’s green-industry agenda.

EU sectors that could benefit from ITMO use ownership clause

Source: TBI analysis

The 12 per cent reduction in EU ETS prices under the 5 per cent scenario would lessen the costs faced by households (via utility bills, which are subject to near-direct pass-through effect from compliance costs) and by small manufacturers covered by the scheme.

Integrity matters greatly. Regulators should treat ITMO use as conditional on robust safeguards:

Integrity filter: Only ITMOs that align with the Core Carbon Principles and secure a corresponding adjustment should count towards compliance.

Volume lock: Firms should only be able to offset 5 per cent of their emissions through the scheme, with this cap monitored for its impact on the ETS price, preventing a repeat of the CDM glut that crashed prices in the 2010s.

Ownership clause: An EU-based company-ownership floor of 20 per cent would enhance domestic political support and business collaboration.

Policy Recommendations to Fix Supply-Side barriers

Carbon markets represent a large and growing opportunity for countries in the Global South to access finance to fund climate projects, but there are steps they must take to ensure that they are prepared to harness the opportunity. Countries that put in place the necessary conditions now to sell international credits can attract early investment.

Short Term

Recommendation: Clearly set out the path to meeting domestic NDCs, and the role that carbon markets will play in helping to achieve economic and development goals.

Governments need a strategy for the role that carbon markets will play in helping them to meet economic, development and climate objectives. This will require clarity over plans to meet their own NDCs and their domestic decarbonisation pathway, including what can be “sold” and what action needs to be retained to meet a country’s own targets. Countries need to carefully consider the potential trade-offs between carbon-market participation and long-term policies to reach their NDCs as well as balancing development objectives and climate objectives.

To avoid overselling ITMOs and losing out on opportunities to reach their own NDCs, host countries could choose to reserve a share of mitigation outcomes generated by mitigation activity for use towards domestic NDC achievement. For example, Ghana has specified that all activities must reserve 1 per cent of mitigation outcomes for domestic use, while Indonesia provides a range of between 10 per cent and 20 per cent for mitigation activities that are included in the NDC.

Setting out clear objectives, priorities and engagement strategies will help send the right signals to encourage project developers and the private sector to invest.

Recommendation: Strengthen domestic frameworks to engage with Article 6 and put in place the necessary policy, regulatory and legal frameworks.

Once countries have set out the role carbon markets will play in meeting their economic and development goals, they need to build their capacity to participate in Article 6.

Article 6 presents the opportunity to unlock significant financial benefits for countries in the Global South. However, to support their participation, countries need to set out robust policy, legal and regulatory frameworks, as well as monitoring systems. To date, many low-income countries lack the infrastructure, technology and institutional capacity to participate in carbon markets, and are yet to set out clear guidelines for project developers.

This requires:

Setting out authorisation criteria, including frameworks and templates for project developers to understand how projects can obtain authorisation ITMOs for use under Article 6

Defining whether the government or the project developer owns the carbon reductions, who can generate ITMO transactions, and how benefits are shared, to ensure communities involved in mitigation activities receive a fair share of revenue

Developing laws and regulations to govern carbon-market activity transactions

Putting in place a clear plan for how to track and manage transactions

Providing technical training to build the skills in government need to develop, validate and verify carbon-credit projects

Investing in better data tracking, auditing and verification, including potentially leveraging some of the technologies such as AI tools for MAC curves, dMRV infrastructure and digital registries, set out in the “Policy Recommendations for Technology Adoption” section earlier in this paper

Setting out a fee structure for Article 6 for project developers, to manage and cover administrative costs incurred by the host country

Ghana has made significant progress in advancing Article 6.2 transactions. It was the first country to launch a framework, develop a national carbon-market registry, authorise a project and submit an initial report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s centralised accounting and reporting platform.

The country’s Carbon Markets Office (CMO) currently has 54 mitigation projects under development, and cooperative approaches agreed with Switzerland, Sweden, Singapore and South Korea. With the Swiss government alone, it has executed eight ITMO transactions. Other countries should look to Ghana’s strategy as a model to follow.

Several actions have led to Ghana’s success:

The country has set out a red list of unconditional nationally determined contribution (NDC) interventions in its carbon-market framework, making it clear to mitigation-outcome buyers that Ghana has no intention of double counting their mitigation outcomes.

Ghana’s CMO, hosted by the country’s Environmental Protection Agency, oversees the implementation of Article 6 activities. It has taken a robust institutional approach: the CMO is enshrined in law, which insulates projects from political change. The CMO has expansive supervisory, regulatory, enforcement and administrative powers.

There is a committee dedicated to the implementation of Article 6 and international carbon-market sales.

The country has provided project developers with template letters for the request, approval and authorisation of transferring ITMOs to ease the administrative process.

Recommendation: Mandate finance ministries to collaborate on carbon-market strategies.

It is critical that the use of international carbon markets serves domestic economic and development priorities, and finance ministries hold the levers to ensure this is the case. This means that they should take a central role in developing and overseeing carbon-market strategies, alongside environment ministries. Finance ministries are also well-positioned to integrate carbon-market revenue into budgetary planning.

Finance ministries should engage in bilateral ITMO negotiations where their economic expertise may be able to help secure better terms in bilateral agreements, inform and assess the economic case for domestic versus international abatement options, and prevent the undervaluation of mitigation outcomes.

Kenya has taken significant steps to empower its finance ministry in shaping carbon-market strategies. For example, in 2021 Kenya’s finance minister announced the development of a national carbon-credits and green-assets registry, centralising and coordinating the strategy development and delivery. Kenya’s finance ministry has also been involved in implementing its NDC and long-term strategies, while considering how to mobilise climate finance and integrate climate considerations into national budgetary processes.

Medium Term

Recommendation: Strengthen South-South collaboration to share systems, knowledge and resources.

Participating in Article 6 requires systems for tracking emissions, approving projects and ensuring environmental integrity. Building these systems can be both time consuming and costly. Where possible, low-income countries should work together to share knowledge and resources. This could include jointly developing emissions inventories and regional project registries. Countries could also look to develop regional MRV platforms to reduce costs.

In addition, countries should consider developing joint carbon-market strategies, where they work together to avoid a “race to the bottom”.

Recommendation: Respond to demand from compliance markets that allow companies to use a fixed share of ITMOs to meet part of their obligations, and support the delivery of credits aligned with their standards.

Various jurisdictions around the world are already or currently considering allowing companies to use international units to meet compliance-market obligations, as recommended in the section of this report on demand-side barriers. But governments in the Global South should take note: these buyers are already, and will likely continue to be, the most consistent and reliable source of demand. These schemes, when they reach full capacity, will represent some 115.8 mtCO2 of annual credit demand, or 64 per cent of total current voluntary-carbon-market demand. Offset demand grew in 2024 thanks to carbon markets that allow offset use, with retirements from these compliance markets representing 24 per cent of retirements in 2024, up from 9 per cent in 2023.[_] This will continue to grow – Germany’s new coalition government has committed to achieve 3 per cent of their NDC with international credits, which would bring this share of the market to 85.2 per cent, and the EU Commission’s proposal for its 2040 targets also now includes the 3 per cent use of international offsets. In addition, the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) is due to become mandatory in 2027, further stretching compliance-market demand.

Size of maximum potential demand for offsets from compliance markets (tCO2)

Source: TBI analysis

As shown in Figure 19, there are clear preferences for the types of credits each country is willing to accept. Singapore accepts most types of credits, but only from certain methodologies. South Korea strongly prefers energy-related credits. Switzerland only accepts projects on a case-by-case basis, and has thus far only invested in renewables and transport projects. Japan’s new Green Transformation (GX) League only accepts removals credits. And the CORSIA is the least selective – allowing almost all methodologies.

Number of credit methodologies accepted in compliance schemes

Note: Switzerland’s Klik Foundation invests in projects on a case-by-case basis, regardless of category. Their data here represent the project methodologies they have already invested in.

Source: TBI analysis – policymakers are welcome to contact TBI for full dataset.

Governments in the Global South have a clear role to play in enabling purchases from these buyer countries. Singapore and Japan only accept projects from countries that their foreign ministries have signed agreements with, due to the need to ensure a corresponding adjustment is carried out at a national level. South Korea and Japan both have policies that favour domestic activities: South Korea requires that international projects have Korean project developers, and Japan’s scheme mandates Japanese-company ownership of projects.

Recommendation: Develop both emissions reductions and removals projects in the immediate term while focusing support on the removals market in the longer term, to align with increasing global demand.

Some companies are turning to high-quality removals credits to meet their climate goals, but supply can be a challenge. There has been a sharp increase in demand for removals credits, which now account for approximately one-third of the market value. McKinsey claims that demand for durable CDR credits could reach up to 100 Mt CO2 by 2030, double the 50MtCO2 in announced supply,[_] as more sectors are looking to enter the market.

This growth in demand for high-quality removals credits presents an opportunity that project developers in the Global South should seek to capitalise on. Governments should support these efforts and build up their own durable removals capacity by setting out explicit roles for removals in their climate strategies. For example, Kenya’s Climate Change Act emphasises removals as well as reductions, and Kenya is now emerging as a hub for removals projects, including enhanced rock weathering (ERW) and direct air capture.

In addition, partnerships between international organisations, governments, private investors and local communities in the Global South, such as the Global Carbon Removal Partnership (formed during COP27), will be instrumental in deploying a wide range of carbon-dioxide removal options to achieve climate objectives.

International carbon markets present an opportunity to fund climate action in the Global South, while helping countries in the Global North achieve their NDCs at lower cost.

Although progress on international carbon markets has been made, it needs to go further, faster.

Outstanding issues around integrity, a lack of clear demand-side incentives, and lack of credible supply mean international carbon markets haven’t yet reached their full potential.

But there are practical steps countries can take to overcome these barriers – including harnessing the latest technologies to overcome credibility concerns, linking compliance markets to ITMOs to stimulate demand, and building the appropriate legal and regulatory frameworks.

Above all, political leadership is essential. Leaders must ensure they understand and can clearly communicate the benefits of carbon markets and take active steps to address political resistance and misperceptions.

It’s time for the world to stop debating carbon markets and put in place steps to scale them.

Appendix: Methodology and Assumptions for the EU Case Study Model

This model estimates the impact of integrating Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) into the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) through to 2050. It calculates potential cost savings, European Union Allowance (EUA) price effects and emissions-allowance adjustments under defined scenarios.

Key Assumptions:

ETS cap begins at 1386 MtCO₂e in 2025 and reduces annually by ~59.6Mt (based on a Linear Reduction Factor (LRF) of 4.3 per cent).

EUA prices grow at 12.88 per cent annually to 2030 and 1 per cent thereafter. This was chosen to peg 2030 and 2050 EUA prices against an average of publicly available EU ETS price forecasts (BNEF, Enerdata, Veyt).

Pre- and post-2030 EUA prices are bifurcated because they represent different trading phases under the EU ETS, and thus have different caps and LRFs.

ITMO volumes are capped at a fixed percentage of the ETS cap (for instance 5 per cent) and assumed to be lower-cost substitutes, not additions. They are assumed to cost €28 ($33) on average, based on an average of estimates (Klik Foundation, Swedish Energy Agency, CORSIA prices).

A price-elasticity-based discount (PED) factor (0.881) is applied to estimate the effect of ITMOs on EUA prices. The PED (0.27) was selected based on recent historical EUA annual average prices and recent verified emissions data (2020 to 2024). A larger sample size returned a different PED (0.13) but was based on much more volatile data (2010 to 2024).

Scenario Calculations:

Annual costs are compared between a baseline (no ITMOs) and an ITMO-integrated system.

Metrics include adjusted EUA prices, cost with ITMOs, and annual savings.

Risk-Adjusted Net Benefit:

The “risk-adjusted net benefit”, also known as a quadratic loss function, was used to optimise the percentage cap of the ITMO usage in the ETS.

It calculates the savings minus the penalty of allowing ITMOs into the ETS and its impact on EUA prices. The penalty grows with the square of the price drop, to represent that larger price shocks to the EUA weaken the price signal disproportionately. The penalty coefficient is set such that a 25 per cent EUA price reduction would negate any potential gain.

The model is deterministic and does not include strategic behaviour, policy feedback or dynamic ITMO pricing. It is intended to support strategic insights around compliance carbon markets that allow ITMO use, rather than precise forecasts of EUA prices.