The rapid growth of non-traditional employment, such as agency, platform and on-call work, as firms adopt new technologies offers valuable flexibility for both employers and employees. But it also shifts the balance of power in the workplace from employees to business owners and managers.

This can expose workers to new labour market risks of precarity and potential exploitation. It can worsen inequality by creating a parallel labour market comprising insecure, poorly paid (often young) workers with limited career prospects. By undermining employers’ incentives to train, it is also bad for productivity.

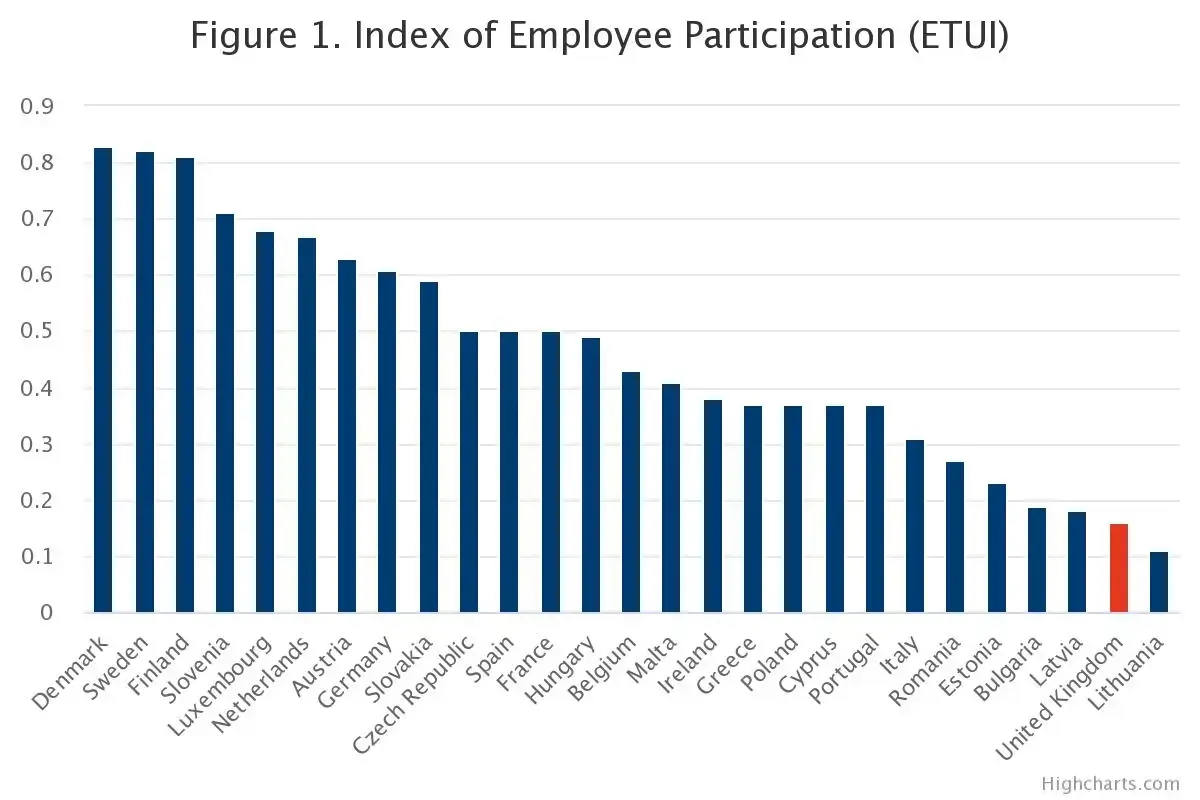

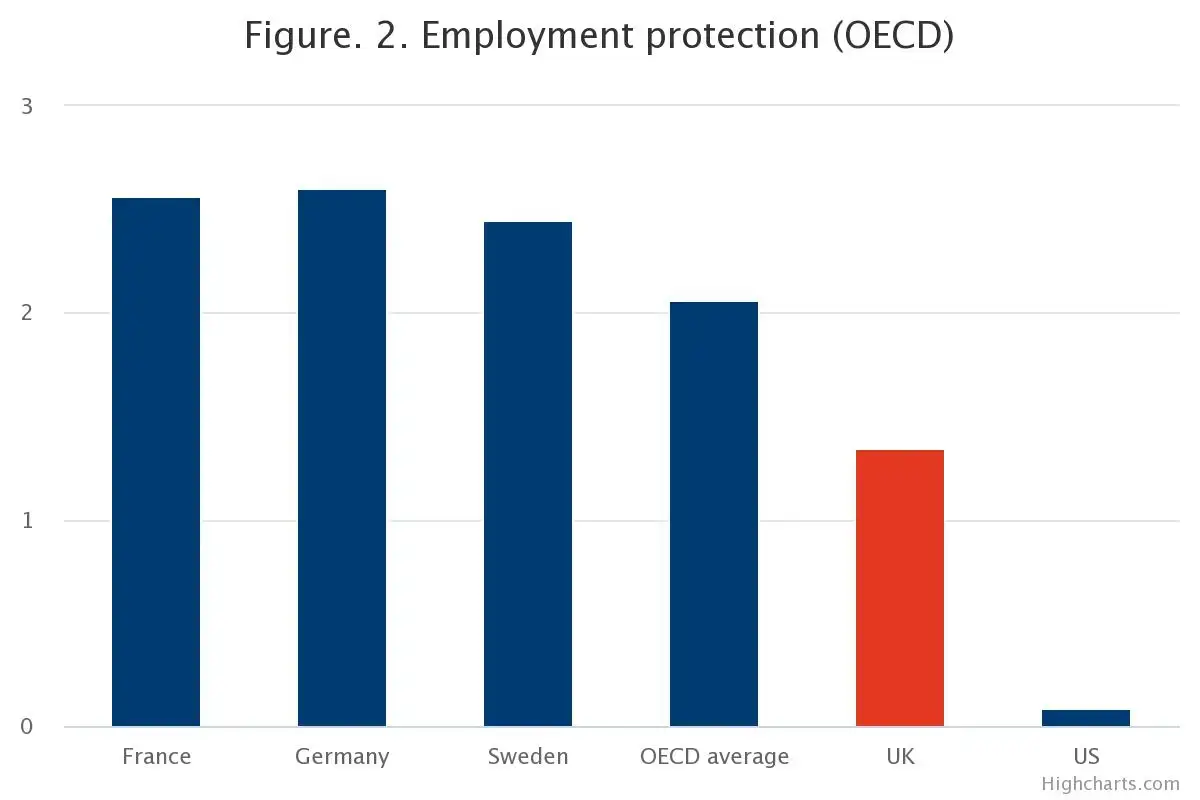

Technology therefore requires a new way of thinking about workers’ rights. But after four decades of labour market deregulation, an individualisation of employment risk and the erosion of collective representation, workers in the UK now have fewer means of redress against infringement of their rights than their counterparts in most other European countries. They participate less in decisions about working practices, are less likely to have their pay and conditions negotiated collectively (Table 1), and have fewer rights against unfair dismissal than elsewhere (Table 2).

Source: European Participation Index, European Trade Union Institute. Note: the EPI is a composite of measures of: 1) Board level employee participation; 2) Establishment level participation; 3) Collective bargaining participation.

While this arguably produces a very flexible labour market highly conducive to job creation in dynamic new technology industries, there is growing concern over individuals’ lack of influence over their own pay, conditions, and prospects.

In devising policies to redress the balance, it’s important to take stock of the huge changes that have taken place in employee relations over the last 40 years. As well as contributing to the growing precarity of work in sections of the labour market, these complicate the task of building counterweights to employers’ demands for greater flexibility and cost-cutting.

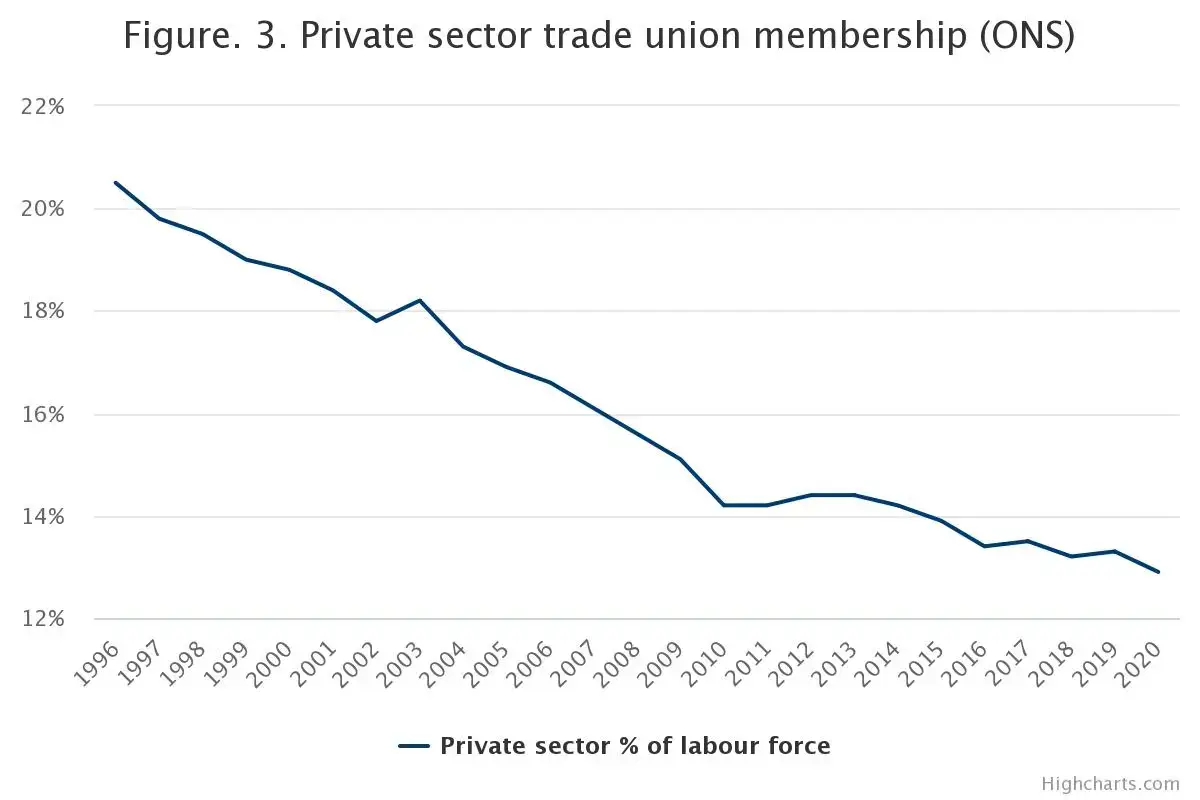

Prior to the 1970s, workplace relations were dominated by powerful trade unions. These relied on their considerable industrial muscle to induce employers to bargain with them and eschewed efforts to build an alternative system based on statutory positive rights. Union membership reached a high of 55% of the labour force in 1979 – the year Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister – but the influence of industry-level bargaining and the wages councils at the time meant around 85% of the workforce was covered by collective pay-setting mechanisms.

Source: OECD. Strictness of employment protection – individual and collective dismissals (regular contracts).

From this position of strength, unions preferred to operate with minimal interference from the state, or much involvement of the courts in the form of the extensive legal guarantees of collective rights at work which are the norm on the Continent.

Thatcher saw overmighty unions as an obstacle to company restructuring, and therefore a brake on productivity growth, and oversaw a concerted attack with three main prongs. First was an assault on union power spanning several Acts of Parliament which restricted their ability to organise, recruit and take industrial action. Second was encouragement of individual, rather than collective rights at work. Third was assertion of the primacy of relatively minimalist labour law over other mechanisms for employee protection.

The impact was profound. Union membership has collapsed to around 24% of the labour force. In the private sector, where the wage-premium from union membership disappeared for the first time in 2020, the proportion is less than half of this (Figure. 3). It is likely to be lower still in non-traditional sectors of the labour market as the decentralisation of work makes it hard for unions to recruit and mobilise.

In essence, the union-dominated system has been replaced by ever smaller pockets of collective bargaining in a rising sea of individualised negotiations and unilateral employer discretion. However, the minimalist legal framework that replaced collectivism is becoming increasingly detached from the realities of work in the new economy.

Thus, from the point of view of workers’ rights, the UK arguably has the worst of both worlds – neither strong, cohesive trade unions, nor a robust enough system of legal protections for workers whose bargaining power in the labour market may be weak.

This vastly complicates protection of workers’ rights, especially in those parts of the digital labour market where, for example, self-employment is the norm or where the very notion of an “employer” has evaporated in favour of freelancer platforms where hours and pay rates are increasingly set by algorithms. This can mean average median pay in some sectors of less than £5 an hour, well below the minimum wage.

Balancing workers’ rights against the needs of employers, whose business models may hinge on the flexibility to respond to fast-changing consumer preferences while rigorously managing costs, will not be easy. But it would be wrong to view this as a zero-sum game, as improving working practices would benefit more productive firms who invest in their staff.

Achieving this calls for a multi-pronged approach that starts by extending more of the protections enjoyed by employees to non-traditional staff in a new Employment Relations Act. But policy must also empower trade unions, incentivise stewardship-minded employers, and adapt the welfare state and legal system to respond to the new organisation of work.