Chapter 1

New research by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR), commissioned by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, shows that a hard Brexit would have more serious implications for Britain’s fast-growing service exports than for its manufacturing exports, and highlights the importance the European Single Market has had for their growth.

In the event of no agreement with the EU—and a reliance on World Trade Organisation (WTO) trading terms—NIESR estimates the UK’s foregone gross domestic product (GDP) due to the reduction in trade in services would be substantial: it would be almost twice as large as that due to the reduction in trade in goods. A Chequers-based agreement would also lead to a substantial amount of foregone output in services.

Using a soft Brexit as a baseline, NIESR’s analysis finds that a WTO-only trading relationship would mean that GDP would be 4.93 per cent lower by 2030 than under this outcome. Of this 4.93 per cent reduction, 2.13 percentage points would be accounted for by a fall in trade in services, with only 1.1 percentage points due to the reduction in trade in goods. Under the Chequers scenario, total GDP is predicted to be 4.13 per cent less, where the reduction due to the loss of services trade with the EU accounts for 1.94 percentage points. In both scenarios, there are effects on GDP arising from other changes such as a reduction in migration.

The analysis highlights the significant risk to industries that create huge value in the UK economy, and whose exports are critical to the UK’s ability to earn the foreign currency needed to finance its import bill. To date, more focus has gone on the risk to goods, for which trade is more high profile, and whose impact will be felt by poorer regions that depend on manufacturing and will likely find it hard to adjust if the UK exits the EU Customs Union and the single market.

However, services have driven three-fifths of the rise in UK exports over the last 20 years—and in 2016, Britain’s surplus on services trade came to almost £100 billion, helping offset a goods deficit of closer to £140 billion. Without Brexit-related disruption, current trends suggest UK services exports would have outstripped goods exports within five years.

Exports of services to the EU are not confined to the southeast. They may be lower in absolute terms in other regions, but proportionally larger parts of services exports from regions such as the West Midlands and Northeast England go to the EU.

The EU is a uniquely open market for cross-border trade in services. It has achieved this openness by adopting common rules and by giving companies the ability to directly enforce their right to trade across borders in the single market.

Due to the single market and low regulatory barriers to trade, the EU is by far the UK’s largest market for services exports. The EU has also helped establish the UK as a hub for service activity, which has boosted trade with non-European markets.

The EU (together with the European Free Trade Association) accounted for 43 per cent of Britain’s services exports in 2016 and is worth around than £110 billion to the UK economy. In the event of leaving the single market, NIESR estimates that this would fall by 65 per cent. The importance of the single market and of the gravity effect of trade is highlighted by the EU’s dominance as a UK services export market. Britian’s second-largest market is the US, with 21 per cent; and third is Asia, which accounts for 15 per cent. The Commonwealth accounted for just 10 per cent that year, while the BRIC economies—Brazil, Russia, India and China—accounted for just 3.6 per cent.

As it stands, it is hard to see where the slack will be picked up. The WTO has not succeeded in opening services markets. Most free-trade agreements do not substantially open up services markets either. To give one example, CETA, the deal between Canada and EU, includes restrictions in trade in sectors covering almost 70 per cent of the UK’s services exports.

What this means is that the British people are being asked to trade the certainty of services companies having full access to key EU markets like financial services for a risky leap in the dark. This is being suggested in the full knowledge that countries like China and the US do not currently offer deals with similar levels of access to their markets. Brexiteers hope that these other countries will break their own precedents and offer the UK a special deal on services. There is no evidence to suggest this will occur.

The impact of a service provider being outside the single market is likely to be worse than a manufacturer being outside the customs union. For a manufacturer, it means products being slowed, onerous checks being applied to verify compliance with EU rules and, in some cases, exports being made more expensive due to tariffs. All these things make trade much more difficult, but not legally impossible. For some types of services, however, the day the UK is outside the single market, UK service exporters may be prohibited from trading into the single market altogether.

The British government has so far failed to address the fact that access to the single market is critical for services. It is proposing mutual recognition of regulatory standards or novel interpretations of equivalence for key sectors. These proposals as they stand are not politically viable. This is because they ask the other countries in the EU to recognise that UK sovereignty is not just equal but superior to each of their own. The UK’s position is that rules decided solely in the UK that diverge from those collectively agreed by the other member states should not affect the ability of UK service companies to continue to export inside the EU.

Brexiteers’ unwillingness to recognise the double standard in simultaneously opposing the existence of collective European institutions and wanting to enjoy a deep and comprehensive services trade deal with the EU threatens to inflict great costs to the UK economy.

Chapter 2

The European Single Market is a unique arrangement that employs three principle tools to boost trade among its member states. First, there are no tariffs on goods. Second, companies and people are free to sell their goods, services or labour, or to invest, in other member states—the so-called four freedoms. Third, it sets common minimum regulatory standards so that exporters are freed of the costs of complying with 28 different national sets of regulations. All goods that comply with European Union (EU) standards can be sold freely across the whole EU. There is nothing comparable with the single market anywhere else in the world.

There is a wealth of evidence that membership of the single market has boosted Britain’s overall foreign trade substantially. HM Treasury, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the UK’s National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR) put the gain at between 35 and 40 per cent. Increased foreign trade increases the competitive pressure on British firms, forcing them to become more productive, which in turn enables them to pay higher wages.

The proportion of UK exports going to the EU fell sharply after the eurozone crisis, when very weak economic growth across much of the currency union hit demand for British goods and services. However, with the eurozone economies now recovering, the relative importance of the EU market is picking up too. British exports of services to the EU have recovered particularly strongly, increasing by 46 per cent between 2012 and 2016.[_]

The share of British imports coming from EU countries has remained broadly stable since the late 1990s. Contrary to the claims of Brexiteers, Britain could not easily boost its imports from the rest of the world and reduce those from the EU. Britain imports so much from the EU because EU suppliers produce the kinds of goods and services that British consumers and firms want to buy. Leaving the single market will not change that but will increase the UK prices of those goods and services by creating obstacles to trade.

Britain may yet step back from the precipice and decide to remain in the EU. Or it might negotiate a sort of Brexit-in-name-only deal with the EU, comprising continued membership of both the single market and the customs union. If so, the damage to Britain’s economy, and to its services exporters, will be less. But what happens if the country does go ahead and leave the single market? What would be the impact on the UK’s world-leading services exporters and on the British economy more broadly?

The impact of Brexit on Britain’s depleted manufacturing industry has captured much of the political attention, with the government being forced to promise car manufacturers and aerospace firms that nothing will change following Brexit. The focus on manufacturing is understandable. When most people think about foreign trade, they tend to focus on goods, especially cars and planes. These factories also tend to be located in poorer areas of the country, where employment losses will be felt most keenly.

Even if the UK remains in, or closely aligned with, the EU’s customs union, the damage to goods trade from leaving the single market will be formidable. Much of the UK’s manufacturing industry is deeply enmeshed in European supply chains, with components needing to flow seamlessly across Britain’s border with the EU for the country to be a competitive place to manufacture.

The loss of industrial capacity associated with Brexit will further denude Britain’s regions of well-paid, high productive jobs, aggravating regional divisions. But it is not manufacturing exports that will be hardest hit by quitting the single market; the really vulnerable sector is services. Most of the growth in Britain’s exports over the last 20 years has been in services. They now comprise around 45 per cent of total exports, and on current trends could exceed half within five years. They are also more vulnerable to Britain leaving the single market than goods exports are.

Despite Britain being highly dependent on services exports to earn to the foreign currency needed to finance its import bill, the impact of Brexit on the country’s services sector has received surprisingly little attention. This is partly because while services account for almost 80 per cent of all UK economic activity, less than a fifth of this is exported. By contrast, manufacturing accounts for 10 per cent of activity, but fully half of this is exported.

Another reason is that financial-services firms are important exporters of services, and these firms are very unpopular, with many voters blaming them for the 2007–2008 financial crisis and subsequent austerity. The UK government has exploited the perception that services exports are synonymous with the City of London to assuage popular concerns about leaving the single market. This ignores that internationally traded financial services are a huge source of employment and tax revenue and that Britain exports many other services, from engineering expertise to long-haul lorry transport.

Few people understand how services trade differs from goods trade, how important services exports are to the UK economy, and what a big hit to this industry would mean for Britain’s public finances and, hence, to public services. Unlike goods, services exports do not face tariffs. But they face a myriad of regulatory obstacles. The EU has made more progress in dismantling the regulatory barriers to trade in services than any other regional economy through its single-market programme. By enabling London in particular to emerge as a hub for a range of high-value-added service activities, the single market is crucial for Britain’s services exports as a whole, not just those to the EU.

This report lays out the importance of services exports to the British economy; the role the European Single Market has played in their rapid growth in recent decades; and what leaving the single market will mean for the industry and for the UK economy as a whole. It shows that the government’s proposed solutions are unworkable and that there is only one way of preventing a major own goal: for Britain to stay in the single market.

Chapter 3

There are no tariff barriers to services trade, but plenty of other barriers. Typically, a services firm based in one country is not permitted to sell cross-border services directly to consumers and businesses in another, and there may also be barriers to a service provider establishing itself in another country to sell its services there. To export to another country, the services firm must comply with the regulations of that country. These barriers are known as non-tariff barriers (NTBs) or behind-the-border barriers. They may be designed with the undeclared purpose of preventing market access by foreign service providers, or they may simply reflect a different set of local preferences, for example different quality standards.

Services exports are also much harder to measure than goods exports. The World Trade Organisation (WTO) breaks services exports down into four different groups, or modes (see table 1). The first mode consists of cross-border services, such as the sale of architectural plans to a foreign client from a UK architect’s office. An example of the second mode would be an Indian student moving to the UK to take a university course, or a French family taking a holiday in the UK. These two types of services exports are captured in the trade data, albeit imperfectly in the case of tourism.

The WTO Categories, or ‘Modes’ of Services

But there are other kinds of services exports. An example of the WTO’s third category would be a British bank setting up in Frankfurt to sell services to German businesses. This is counted as UK foreign direct investment (FDI) in Germany. An example of the fourth mode would be a UK construction worker temporarily employed by a British firm on a project in Italy. Neither the third nor the fourth mode is counted as a services export, because the services are provided from Germany rather than the UK and the worker continues to be paid from the UK rather than Italy. However, the British bank needs to be free to set up in Germany, and the British construction worker must be free to relocate temporarily to Italy to complete the contract.

Services exports also take the form of intermediate inputs in the production of goods, which are then exported. For example, the legal services and trade finance bought by an UK manufacturer to allow it to export to the United States (US). According to the WTO, 21 per cent of the value of British exports of manufactured goods comprises British-sourced services, and a further 16 per cent consists of foreign services.[_] Because these services are embedded in manufactured goods, they are classed as manufacturing exports, making it harder to calculate the relative values of trade in goods and services.

Rising Services Trade

Foreign trade used to largely comprise the trading of finished manufactured goods. But rising incomes—as people get wealthier, they spend a higher proportion of their incomes on services—as well as advances in communications technologies and the globalisation of trade and finance have driven the growth in services trade. While still relatively small compared with the overall goods trade, there are some notable national trends. Services exports have risen more rapidly than goods exports in most developed countries, but by nowhere near as much as in Britain (see figure 2).

G7 Countries’ Services as a Share of Total Exports, 1995–2016

Services accounted for almost 45 per cent of Britain’s exports in 2017, easily the highest proportion among the G7 economies, and the UK is the largest exporter of services in absolute terms in the world after the US (see figure 3).[_] Over the last 20 years, the value of Britain’s goods exports increased by two-thirds, whereas the value of its services exports almost quadrupled. Indeed, over this period, fully three-fifths of the growth in British exports took the form of services, a massively higher share than in other developed economies.

G7 Countries’ Exports of Goods and Services, 2016

Chapter 4

Why does the UK depend so much more on services than comparable countries? This is partly down to successive British governments neglecting the needs of manufacturing. Growth in Britain’s exports of manufactured goods has been easily the weakest of this group of advanced economies. For example, in 1995 German goods exports were twice Britain’s; by 2016 they were three and half times Britain’s.

But it is also because of Britain’s growing comparative advantage in commercial services. The rapid expansion of global financial activity has been an important factor behind this; given its existing specialisation in finance and business services, Britain was ideally placed to profit from increasing financialisation.

Another major driver was the completion in 1992 of the European Single Market, which opened the door for greater trade in financial and other business-related services across EU borders. This enabled Britain to carve out a profitable link in Europe’s division of labour. For example, German manufacturers selling goods to China often use UK-based firms for financial and legal services. Export of services are now equivalent to around 13 per cent of UK GDP, compared with 8 per cent in Germany and just 4 per cent in the US.[_]

The UK’s surplus on the trade in services was £94 billion ($124 billion) in 2016, helping to offset much of the £135 billion ($178 billion) deficit on the trade in goods (see figure 4). Bar an unprecedented renaissance in UK manufacturing—and depressed investment in the sector strongly suggests this is not about to happen—Britain will remain dependent on services exports to pay for its imports of manufactured goods.

Balance on UK’s Trade in Goods and Services, 1970–2016

This is not in itself a problem; there is no reason to fetishise manufacturing. But the scale of Britain’s dependence on services does create vulnerabilities. One is the prospect of financial deglobalisation and shrinking demand for its financial and business-services expertise. This could happen if the next financial crisis prompts governments to step up regulation of the sector. Another risk is a loss of unimpeded access to the single market. If a country refuses to accept the EU’s legal jurisdiction, it is treated as a third country, and the free exchange of workers and services is limited.

Financial and business services, which include everything from investment banking to advertising, dominate Britain’s services exports, but it would be wrong to reduce the industry to this sector. Britain is also a major exporter of telecoms services, engineering and architecture expertise, shipping, education, transport and intellectual property (see figure 5). Surpluses on all these sectors more than offset a large shortfall on tourism: more Britons holiday abroad than foreigners holiday in Britain.

UK Services Trade by Sector, 2015

London and Southeast England dominate Britain’s services exports, and even adjusted for their much greater economic size, these two regions are more dependent on services trade other parts of the UK are (see figure 6). However, were the services exports of these two economies to fall sharply, the rest of the country would suffer too: London and Southeast England form the motor of the UK economy, and tax revenues generated there fund public services across the country.

While services exports are much lower in absolute terms than other parts of the country, regions like the West Midlands and Northeast England export a proportionally even larger part of services to the EU than to other parts of the world.[_]

Value of Services Exports by UK Region, 2016

Europe Dominates the UK’s Services Trade

The EU and the European Free-Trade Association (EFTA), which consists of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland, accounted for 46 per cent of British services exports in 2017; the US accounted for 22 per cent and Asia for 17 per cent (see figure 7). While the EU and EFTA share was unchanged relative to a decade ago, the US proportion had fallen sharply from 28 per cent, while Asia’s share had risen from 14 per cent.[_] The Commonwealth bought less than 10 per cent of Britain’s services exports in 2017, pretty much unchanged from a decade earlier, while the BRIC economies—Brazil, Russia, India and China—accounted for just over 3 per cent.

Britain’s Services Exports by Market, 2017

While trade with the BRICs has risen relatively rapidly (they purchased closer to 2 per cent of Britain’s services exports in 2016), exports of services to these four economies would have to increase 15-fold to equal the size of exports to European markets. Strikingly, Britain exported more services to Ireland in 2017 than to the four BRIC economies together.

Why the UK Sells So Many Services Across the EU

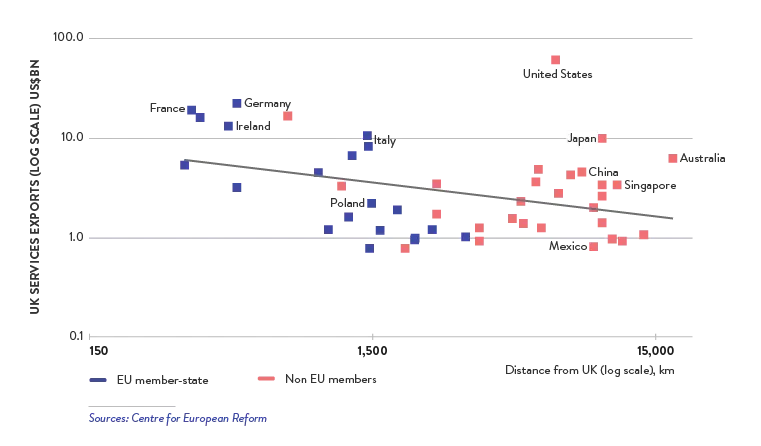

Why is Britain’s services trade with the EU so high? One reason is the so-called gravity effect: countries tend to trade with large economies and ones that are nearby. The EU fulfils both criteria. Contrary to the claims of Brexiteers, Britain has not entered a post-geography trading world (see figure 8). The effect of distance on trade in services is smaller than its effect on goods trade—transport costs are less of a factor for services than for goods—but it is still significant: a 10 per cent increase in distance between countries reduces services trade by 7 per cent.[_] That effect has been diminishing (very slowly) over time with improvements in communications technologies and cheaper air travel, but it remains strong. A common language does have some positive effect on services trade between countries, but a former colonial relationship does not appear to have an impact.[_]

UK Services Exports to Selected Countries

The other reason the UK conducts so much trade with the EU is that single market rules are much deeper than any standard or modern trade agreement and cover all modes of services and most sectors.[_] The UK government’s 2013 review of the balance of competencies between the UK and the EU estimated that 90 per cent of services are covered by EU legislation.[_]

There is a presumption in favour of home-country regulation, or mutual recognition, for cross-border services. Host EU member states can impose additional regulation but must be able to demonstrate that it is necessary in the public interest as well as being non-discriminatory and proportionate. This is policed by the European Commission and by private actors who can access national courts, which can refer cases to the European Court of Justice. And membership of the single market gives rise to higher trade in goods, which in turn boosts trade in services.

Member states have also agreed to harmonise domestic regulation in particular areas, enabling service providers to operate across the EU under one set of rules. This is facilitated by majority decision-making among EU governments. Enforcement is built into national legal systems, and service providers can enforce it in national courts. The European Commission is empowered to actively pursue and sanction breaches. Licensing is also conducted by supranational agencies in a number of sectors.

EU legislation that opens services sectors includes so-called horizontal legislation that applies across all services sectors, such as the Services Directive and the Professional Qualifications Directive; profession specific legislation such as that covering legal services; sector-specific legislation covering sectors such as telecoms (which are excluded from the Services Directive); and rules that go wider than services such as the harmonisation of consumer-protection laws.

In short, the enforcement mechanisms to reduce barriers to trade are much stronger and more extensive under EU law than under the WTO’s General Agreement on Trade and Services (GATS) or under free-trade agreements brokered between countries or trading blocs. In addition, these democratic institutions are permanently in place, so they can agree to extend any single set of joint rules if it transpires that the first set of single rules is insufficient to reduce the barriers to trade.

Chapter 5

But does Britain’s membership of the EU constrain its services exports with the rest of world, as many Brexiteers contend? As the obstacles to trade in services are regulatory rather than tariff based, it is hard to see how this could be the case. By ensuring minimum standards, the EU has facilitated trade in services, not hampered it.

Eurosceptics routinely ignore this. In a report published in September 2018, the Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA) began with the premise that the EU’s regulatory efforts are anti-competitive. To prove this, the IEA cited five descriptive examples of specific regulations that comprise a minuscule fraction of total EU regulation, and this handful of descriptions falls far short of the standard of a cost-benefit analysis of each measure. For any serious analysis to conclude that the EU’s regulatory efforts deserve to be considered anti-competitive, it would be necessary to conduct a much wider analysis across all regulatory measures.

Interestingly, such an exercise had been partly attempted—but the IEA omitted to mention this. Open Europe found that the average cost-benefit analysis of EU legislation adopted between 1998 and 2009 in the UK was 1.02.[_] In other words, the average ratio of economic gains to losses from adopting new legislation was positive and gains outweighed the costs by 2 per cent. However, in this specific period, 40 per cent of EU legislation was employment and environmental legislation, which may explain why it gave rise to relatively low economic gains. One might expect that earlier rounds of regulation that focused more on opening markets would have provided a higher ratio.

Adopting the prior assumption that EU regulation is bad for UK business supplies the motivation for the IEA’s Plan A+: to agree an FTA with the EU rather than any agreement that would involve some form of alignment. The IEA argued that the UK should be able to press the EU to accept a liberalising FTA (as defined by the UK) because the UK will be able to obtain such agreements with other countries, like the US, and this will put pressure on the EU. Looking at services, one major flaw in this logic is that other countries, including the US, will not grant mutual recognition for many services, so the posited pressure on some important services for the UK will never arise.

A further flaw is that the IEA assumed that the EU’s regulatory stance is protectionist across the board and worse than that of the US, but did not show this to be the case. It is not just that mutual recognition may not be available with partners like the US; the freedom to enter the market at all may not be available. To give two examples, the US does not allow third-country providers to provide airline services between cities in the US, and UK airlines would not be accorded such a right in a UK-US trade deal. UK airlines already have such a right within the EU; the EU mirroring the US deal would leave Britain in a worse position than the one it enjoys now. The same is true with respect to providing cross-border retail financial services. It is important to remember that the UK’s point of comparison now is what it can obtain in the single market—whether as a member of the EU or the European Economic Area (EEA)—not what the EU or the US offers third countries.

Another major flaw is that the IEA appeared to ignore the gravity model altogether. In a purely mercantilist negotiation, the consequence of the costs of distance would be that EU would not have to match the terms of a US offer to make an equally economically compelling offer to the UK.

In other words, the IEA suggestion is essentially a call for an FTA with allegedly greater negotiating heft supplied by threatening to do other deals on a bilateral or multilateral basis.

Eurosceptics are also wrong to argue that the EU will inevitably become a less important market for the UK because the EU economy will grow less rapidly than the US or major emerging markets, such as China and India. The best prospects for rapid growth of services are between countries that align their regulations sufficiently to make the trade of services possible. There is nothing to suggest the US, let alone China or India, is minded to facilitate increased services trade by harmonising its regulations with the UK or by agreeing that British firms could sell services in its markets under UK rules.

Indeed, it is abundantly clear that the UK stands a better change of prising open these markets from within the EU than from outside it. The reason is that leverage is crucial to gaining market access. By virtue of its size (over a quarter of global output and a population of 500 million), the EU is in a strong position when it comes to trade negotiations: the bigger the domestic market, the greater an economy’s negotiating power. British Eurosceptics ignore the importance of reciprocity.

China and the US together account for a fifth of global imports of commercial services. The UK should (eventually) be able to strike a deal with these two behemoths; the question is whether it would be in its interests to do so. The UK’s balance-of-competencies review concluded that on the basis of Australian and Canadian experiences of negotiating with the US, Britain would struggle to broker a fair deal. Like Australia and Canada, the UK would have little leverage, as a deal would be far more important to the UK than to the US.[_]

Moreover, one of the obstacles to the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), a proposed agreement between the EU and the US, was financial services. The EU, reflecting UK priorities, sought to expand financial-services access and create institutional mechanisms for reducing future regulatory divergence between the US and the EU; the US ruled this out. Moreover, in any deal with the UK, the US will also demand the UK open up its market for health services, which any British government will find very hard to agree to.

China could potentially become a large market for British exports of commercial services as the Chinese economy rebalances away from its preponderant dependence on heavy industry. China will be an even tougher nut to crack than the US. At present the Chinese government imposes a series of formal and informal restrictions on imported services. Services trade between the EU and China is currently dominated by travel, tourism and transport services related to the trade in manufactured goods between the two trading blocs, rather than by services sold by EU enterprises to Chinese customers. China’s trade deal with Switzerland is very one-sided, giving an indication of what Britain could expect. [_]

Negotiations with the other BRIC countries—Brazil, Russia and India—will be just as hard. None has shown any interest in opening up its services sector to greater international competition. The only chance the UK has of levering open these markets would be from within the EU, although even this is unlikely to succeed. It is worth noting that the US has consistently failed in its attempts to open these economies’ services markets.

Chapter 6

Financial Services

Brexit will hit Britain’s services trade not only with the EU but also with non-European markets. Exports to the EU have helped establish the UK as a hub for financial and business services. Providing services to EU-based clients has helped UK-based services providers achieve the scale and the ecosystem of complementary businesses needed to export to non-European markets.

The loss of unimpeded access to the European Single Market will undermine this status. For example, if London-based financial institutions lose their EU passporting rights—the right to sell financial services across the EU—many will move some of their activities out of London and into the EU, to avoid the costs of complying with multiple sets of regulations. This will reduce the UK’s financial-services exports to the rest of the world, in turn hitting associated industries such as legal services, telecommunications and consulting.

Services firms have little power under WTO rules or FTAs to enforce their rights of market access.[_]The government of a firm’s country of origin has the discretion to do so on their behalf, but governments only bring a small number of cases, and typically only on behalf of very large companies like Boeing or Airbus. By contrast, in the EU every national court and tribunal must and does apply EU law to protect the rights of all EU citizens and businesses, regardless of their member state of origin. In addition, the European Commission actively pursues infringements of EU law.

The commission alone formally pursues around 1,000 new cases of single-market infringement a year against member states.[_] By contrast, since 1945, the WTO and its predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), have dealt with just 500 dispute settlements, and only 28 of these pertained to services.[_] This comparison underplays the degree of enforcement capacity in the EU, because the primary agents of enforcement in a devolved system like the EU are national courts and national administrations.

E-Commerce

London’s status as a tech hub, and the success of British industries from finance to pharmaceuticals, requires data to flow freely between the UK and the rest of the EU. More and more businesses are data driven and are pooling data across the EU. Under EU rules, citizens have a fundamental right to privacy, including the right for their personal data to be forgotten from Internet search engines. The UK government is pushing to mirror the EU’s data-protection standards after Brexit in a bid to ensure that data continue to flow freely. It proposes a special deal with the EU, under which the UK would leave its standards aligned with those of the EU but would have a say over the evolution of those standards in future; that is, the government is pushing for a form of mutual recognition following Brexit.

The EU has already indicated that this will not fly, citing the same reasons as for its rejection of mutual recognition in other areas: the absence of common supervision and a common court to enforce compliance. Instead, the EU has told the UK government that it will have to negotiate a so-called adequacy agreement that proves British data-protection standards meet EU ones and will continue to do so over time. Several countries have such agreements with the EU, including New Zealand and Argentina. Britain can broker a similar one but will be a rule taker; if it diverges from EU standards it deems too onerous, the agreement could be suspended.

If the British government balks at the one-sidedness of an adequacy agreement, or there is a delay in reaching one until after the UK has exited its transition status on 31 December 2020, the UK will sacrifice a chunk of the benefits from burgeoning cross-border e-commerce in Europe. Currently, three-quarters of the UK’s cross-border data flows take place with other EU countries. This is because the EU has gone further than anywhere else in removing the obstacles to data flows by establishing common standards. The UK has profited from this, with London emerging as by far Europe’s most important hub for tech start-ups and the tech sector more generally.

This hub status also relies on the free flow of skilled labour between the UK and the rest of Europe—directly, in terms of the freedom of firms to seamless hire the best people from across Europe, and indirectly, through the ability of UK universities to attach the best talent. The links between the UK’s world-class universities and the tech sector have been crucial to driving the success of the latter. A cumbersome visa regime—all but inevitable unless Britain remains in the EEA—threatens all of this.

Road Haulage

Historically, European countries issued only a restricted number of licences for road-haulage operators from other countries to operate on their territories. The EU has required its member states to open markets to road-haulage firms from other member states. As a result, it is possible not only for a UK road haulier to deliver goods from Sunderland to Germany, but the lorry can also then pick up goods in one German city and deliver them to another, or it can deliver goods between two other member states on the same or even separate circuits.

These rights do not apply to road hauliers from countries outside the EU, which are allocated licences and then have to apply for additional ones. This has been shown to have substantial impact on trade with Turkey.[_] For a Turkish haulage firm to make a delivery from Istanbul to Paris, it needs to apply for a licence from each EU member state between Turkey and France. After Brexit, under the existing international treaties that would apply, the UK might have access to up to 1,225 permits for the 300,000 journeys made by the 75,000 or so British hauliers. The British government has legislated to put in place a rationing scheme for the permits in the event there is no withdrawal deal with the EU.[_]

Rail Freight

EU rules require member states to put in place non-discriminatory and proportionate licensing arrangements for rail-freight operators. The EU has also begun to require that member states oblige their national railway operators to make access available to track and other railway systems so that freight-service providers can piece together trans-continental freight services over the patchwork of national rail-track systems. The EU has facilitated the adoption of common standards so trains can run across Europe; different national product and safety standards previously prevented this.

EU action in this area was important because restricting rail freight to a series of national monopolies was killing off the industry. Rail freight generally becomes competitive with road haulage only over distances of more than 600 kilometres, and routes of this length are typically cross-border.[_] Without the ability to compete across borders, rail freight had become largely irrelevant. The carriage of freight by rail in the EU declined in volume terms from 32 per cent of the total in 1970 to just 8 per cent in 2003; by comparison, 40 per cent of US freight is transported by rail.[_] Rail freight also provides a good example of the importance of the European Commission as a resourced institution committed to pursuing the deepening of the single market and pushing member states to deliver. The EU is onto its fourth rail legislative framework, and a Europeanised system is gradually coming into existence.[_]

Telecommunications

BT is the largest provider of cross-border telecoms services to businesses in the EU. Like the rail example, BT’s services run over underlying networks partly put together with network components provided by other national operators. Under GATS, if a country opts to sign up to the telecoms reference offer and sets in place no exclusions, then it ought to have in place a national regulator to ensure non-discriminatory access. However, there is no requirement for any rules or institutions outside GATS to control whether effective regulatory activity takes place: without this, there would be no usable supply of fairly priced national components.

In the EU, national telecoms regulators have to submit to the European Commission their detailed plans for achieving non-discrimination. The commission can reject key elements if they are inadequate. The commission can also take enforcement action against member states for failing to implement if the regulator does not act. Competitors from elsewhere in the EU can separately take a case in national courts.

In addition, the information that the sectoral regulators must supply to the commission informs it in its capacity as a competition authority, and potential private litigants in places where national telecoms network providers are likely to be abusing their dominance because they are not subject to effective regulation. BT’s success in using EU rules to build a pan-European network is why its customers include both the European Commission and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO).

Aviation

As with rail and telecoms, most EU member states historically restricted the supply of aviation services to a single national operator. The EU has required its member states to gradually open their aviation markets, and the process is now complete. An EU-based air carrier can generally offer a service on any route between two EU destinations. This makes it feasible for low-cost operators in the UK to offer services not only between the UK and another member state but between cities in other member states, for example easyJet flying from Paris to Rome.

Unless the UK reaches a deal with the EU, UK airlines will not secure such wide access rights after Brexit. EU rules extend beyond allowing access to routes to include ensuring non-discriminatory access to slots at national airports. Consumer-protection and air-safety rules are also harmonised to ensure that operators cannot attempt to compete by cutting standards, and so that no member state can exclude an operator from its market by setting national standards aimed at keeping out competitors.

Chapter 7

Trading Services Under WTO Rules

Under the WTO’s General Agreement in Trade in Services (GATS), participating countries can include specific service sectors that they are willing to open up to foreign competition; any service that is not specifically listed is deemed not to have been liberalised. GATS agreements can specify how the foreign supplier will be allowed to service the host country’s market. For example, it may be required to be present in the host country and forbidden from supplying services on a cross-border basis. GATS signatories must also observe the most-favoured nation principle: any trade liberalisation extended to one country must be extended to all.

Moreover, EU member states’ liberalisation commitments under GATS were made before trade policy became an exclusive EU competency.[_] Consequently, trading under GATS rules would mean UK service providers having to abide by a different national trading regime in each EU member state.[_]

Trading Services Under Free-Trade Agreements

Free-trade agreements (FTAs) can provide an exception to the general GATS regime and allow one country to favour another as long as:

the agreement does not increase restrictions for other countries;

the agreement has “substantial sectoral coverage”; and

there is no a priori exclusion of any of the four modes of supply (which is to be distinguished from exceptions or restrictions to the modes of supply that are acceptable).

EU FTAs make few commitments regarding the cross-border (mode 1) trade in services, including financial services. For example, there are no passporting rights, with financial firms expected to fully locate in the EU to serve retail markets. The EU’s offer is typically highly circumscribed when it comes to mode 4 services, reflecting visa requirements and very little recognition of third-country standards. The following services have always been subject to tight EU restrictions: audio-visual services, services in the exercise of government authority, air transport and maritime trade in the territory. There is usually a requirement for some voluntary regulatory cooperation focusing on the exchange of information in a limited number of sectors. But the parties normally retain complete regulatory autonomy.[_]

The UK’s hostility to continued free movement of labour is a problem as regards the delivery of services. Mode 4 services exports take place when a representative of a firm is temporarily posted abroad to deliver a service. This is straightforward in the EU due to free movement of labour between member states. However, once the UK leaves the single market, workers will require business visas to temporarily relocate. The EU will in all likelihood impose similar requirements on workers from the UK to those the UK imposes on business visitors from the EU. No FTA has ever come close to giving services providers the flexibility to provide mode 4 services in the way they can in the EU’s single market.

Despite improvements in communications technology, services transactions still depend heavily on an element of face-to-face contact. The freedom of people to move unrestricted throughout the single market, coupled with the wide and deep mutual recognition of professional qualifications in the EU, means that such contact can be achieved cheaply, increasing competition and productivity.

Trading Financial Services Under FTAs

The financial-services industry has systematic properties that most other industries do not. Regulators and politicians will not allow a firm from outside their regulatory jurisdiction to sell services unless they are confident they can hold that firm to account, or force it to compensate its citizens when things go wrong. Following the 2007–2008 financial crisis, which began in the US but created havoc across the world, governments are understandably wary of expanding mutual recognition of regulatory standards without common institutions capable of adjudication and enforcement.

The fact that an FTA could in theory liberalise cross-border trade in financial services does not mean it is likely to do so. It would be unprecedented for the EU to do so with Britain; there is not a single trade agreement in the world that is genuinely open to financial services.[_] Indeed, the European Council, which brings together EU heads of state and government, has stated that in any deal with the UK, host-state rules will apply for financial services alongside a framework for voluntary cooperation.[_]

It is sometimes claimed that because the EU was prepared to include a financial-services chapter in the proposed TTIP negotiation with the US, it is treating the UK unfairly by refusing to include passporting rights in any FTA with the UK.[_] This is a misunderstanding drawn from confusing principle and substance. Modern FTAs like the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) and TTIP include financial services in principle, but they are so riven with exceptions that in practice there is very little market opening.

What will this mean for financial transactions between the UK and the EU? The UK will effectively trade with the EU under rules set by the WTO, which covers services sectors only very thinly. Service providers would have to apply for comprehensive licences in both jurisdictions and have all the necessary elements of a fully functioning bank up and running in both places.

Banks will have to establish basic entities in the other economic area—the remaining 27 EU member states or the UK—to continue doing business. The concept of a basic entity is not easy to define. The European Central Bank has indicted that it will not accept empty shells or letterbox companies whose business effectively continues to be run from London. For critical functions such as management, controlling and compliance, qualified personnel need to be present at the EU entity at all times.[_] This would mean that UK financial firms could repatriate profits earned in the EU but that the host state would benefit from the economic activity and tax generated.

Canada-EU Free Trade Agreement

CETA is a free-trade agreement between the EU and Canada and conforms to the general description of EU FTAs above. The main innovation in CETA compared with the EU’s other FTAs is that it reverses the listing of commitments. Any service that is not listed is assumed to have been liberalised. This also means that services that do not currently exist are a priori liberalised. Thanks to this arrangement, all sectors enjoy greater market access under CETA than under WTO rules (see figure 9).

However, there are restrictions under CETA in sectors that cover almost 70 per cent of the UK’s services exports. With respect to financial services, liberalised sectors are limited to certain types of insurance (maritime transport, commercial aviation, space launching and freight), reinsurance, certain banking-related services and portfolio management. They can all unilaterally be curtailed for prudential reasons.

Market Access Under CETA vs. WTO

Chapter 8

Mutual Recognition of Regulatory Standards Will Not Fly

The UK’s initial approach to this problem was to argue for mutual recognition. In other words, UK providers authorised and regulated in the UK would, given the similarity of UK and EU regulation, be able to access EU markets, and vice versa for EU-based providers. This arrangement would potentially apply to all financial services products. The UK referred to regulatory outcomes over time, meaning that this is a system in which the rules and practice do not have to be the same but similar high-level goals such as good consumer protection and prudential security are pursued. Where the high-level goals were not obtained, the British offer seemed to be that there should be a body capable of determining this and enforcing suitable sanctions, proportionate to the degree of breach. This should be supported by institutions that bring together the respective EU and UK regulators in constant dialogue.

Is this offer legally feasible? The issue from an EU perspective is whether it gives an external court the ability to rule on matters of internal EU law. In place of the ECJ, mutual recognition would hand jurisdiction to a new dispute body, on which there would presumably be an equal number of UK and EU judges (or representatives, if it were a political body)—as opposed to the current situation, where the UK has one judge out of a total of 28. Once set up under the EU treaties, the dispute body might become the ultimate arbiter of financial-services regulation between the EU and UK. While it would be unable to overrule domestic regulation directly, it would create indirect pressure to do so via trade sanctions.

A judicial body would find it hard to assess regulatory outcomes over time, except in the most general terms, making it difficult for it to find a breach. In all likelihood, mutual recognition would be rescinded only after a weakening of prudential rules had caused a financial institution to run into trouble or triggered a financial crisis. There could be a concern that a legal body adopting rules based on a narrower set of concerns than those taking into account broader socio-economic considerations, as the ECJ does at present, might be too accepting of the risks generated by divergence.

The dispute body might be more cognizant of wider concerns if it were a political body operating under delegated authority from national political institutions. However, the impetus would still likely be for the overall regulatory regime to favour the system with less onerous regulation. This is because the default would be mutual recognition, so a body on which there was stalemate (assuming equal representation between the EU and the UK) would be obliged to keep market access open. It would also be less democratic than the current system, where the European Parliament votes directly on financial-services legislation.

The EU has understandably ruled out such an approach. It would comprise a more beneficial form of mutual recognition for the UK than enjoyed by a member of the EU. Mutual recognition in the EU is not absolute, but conditional. That means in the first instance that if something is considered good enough for the market of the home member state, it is deemed good enough for the markets of all the other member states—but this is tempered in two ways. First, a host country can show a good public policy reason why it should be allowed to impose stricter standards and hence potentially restrict trade. The ECJ determines whether the state has a strong enough justification to place such obstructions in the way of market integration. Second, the member states, in harmonising legislation, also frequently collectively decide—in conjunction with the European Parliament—whether to set minimum or maximum standards, and this may overrule a minority of member states that must then change their standards.

While many in the UK perceive this as a symmetric negotiation between the UK and the EU, from an EU perspective it is an asymmetric negotiation between the EU and a third country. The EU is conscious that the negotiation might not be a one-off; it could establish a precedent for negotiations with another member state that opts to quit the union, and for negotiations with existing and potential candidates for accession to the EU as well with other countries with which the EU has or is negotiating FTAs. If multiple countries enjoyed the mutual-recognition arrangement suggested by the UK, it would be difficult to establish common single-market rules because market participants could simply relocate to bypass them.

Equivalence Would Leave Britain a Rule Taker With Little Market Access

What about so-called equivalence, the mirroring of each other’s regulatory standards? This has been discussed mostly in the context of financial services. Equivalence would not grant generalised passporting rights for British financial institutions, but instead allow EU financial institutions to access products from third countries (in this case, the UK). Equivalence is really a prudential ruling allowing EU financial institutions to hold assets from the third country; it is not a measure to liberalise trade in financial services between the EU and another country.

Equivalence between the EU and UK would not cover all financial services, and where it did, it would do so on EU terms. The UK would have to ensure it was equivalent with EU rules and prove that there was no divergence between its rules and the EU’s over time. In other words, the UK would be a rule taker—something the UK authorities have ruled out. The best that the British could perhaps hope for is a kind of super-equivalence, under which the UK would share control over the processes by which equivalence was granted, but not over the content of the regulations or the decisions.

What would this mean in practice for UK financial firms? Equivalence is not available for cross-border services to retail customers or wholesale banking services (deposit taking and lending) to corporate customers. Investment banks providing services to EU-based financial institutions could benefit from equivalence, but not investment banks providing services to non-financial corporates. The inability to provide cross-border wholesale and investment-banking services to corporate clients is likely to cause the largest of loss of revenue post-Brexit.

UK-based fund managers would also lose the ability to service retail clients on a cross-border basis. However, portfolio management by UK providers would be feasible, assuming the rules of each individual EU member state provided for this and that there was cooperation among all relevant regulatory authorities. Most big UK fund managers have subsidiaries in Dublin and Luxemburg, which they would have to expand to make sure they are not deemed to be letterboxes. The big hit would be to small and medium-sized UK fund managers that do not have offices in other member states and lack the scale to establish them.

The impact on insurance firms would be relatively less severe. British insurance firms would be allowed to offer reinsurance products to EU-domiciled professional clients but not to offer direct insurance to retail customers in the EU. They would not be a major problem for insurers as most have substantial subsidiaries in other member states through which they conduct retail business. However, there would be legacy problems, for example where EU customers have been sold insurance products (such as pensions) directly from the UK. Unless legal provisions are made to grandfather these contracts, insurers would not be able to honour them.

Would equivalence mitigate financial-sector losses significantly? The consultancy Oliver Wyman has estimated that leaving the single market and being treated by the EU as a third country with no equivalence rights would cost the UK financial-services industry £18–20 billion ($24–26 billion) a year, 31,000–35,000 jobs, and the UK treasury £3–5 billion ($4–7 billion) in lost tax revenue.[_] However, if the indirect costs to the financial ecosystem as a whole (the loss of scale on business due to higher costs, less specialisation and less innovation in financial technology) are included, the figures increase substantially, to £32–38 billion ($42–50 billion), 65,000–75,000 jobs and a tax loss of £8–10 billion ($11–13 billion). This represents a 20 per cent reduction in size of the UK financial-services industry.

These figures do not include the multiplier effect on the economy as a whole, which the Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates at 1.5; that is, for every £1 million of lost financial business, the overall loss of economic activity would be £1.5 million. Under an equivalence regime—including delegation of portfolio management on behalf of institutional clients services and bilateral agreements with other EU member states regarding reinsurance—the reduction is business might be limited to £20 billion ($26 billion) and the lost tax revenue to £5 billion ($7 billion).

The government’s white paper on the future relationship between the UK and the EU abandons the pursuit of mutual recognition and recognises that the EU and the UK will want to preserve their respective regulatory autonomy and will base the regimes for permitting access to third countries on equivalence.[_] However, the UK appears to be seeking to push the terms of equivalence for UK financial services at least some of the way towards mutual recognition. It is arguing that:

there should be an extension of equivalence to more areas that are commercially important for UK providers;

there should be safeguarding of rights acquired by a commercial operator—this is presumably intended to apply when the UK rules diverge and the commercial operator is no longer subject to rules in the UK that are equivalent to EU ones; and

potentially an independent arbitration body, rather than EU authorities, could ultimately determine whether equivalence has been breached.

(The text declines to state in respect of which financial rules the independent body would adjudicate). Objectives 2 and 3 would not in fact be consistent with the EU retaining full regulatory autonomy.

Chapter 9

What will be the economic impact of trading services with the EU under an FTA, as opposed to within the single market? The National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR) estimates that cross-border services could fall by up to 60 per cent, compared with a fall of up to 58–65 per cent in goods exports. The NIESR calculates that the latter decline could be curtailed to 35–44 per cent if the UK succeeds in signing an FTA with the EU, but that this would not mitigate the loss of services trade because such an FTA will do very little to dismantle non-tariff barriers.

With services exports to the EU (and EFTA) accounting for 46 per cent of total services exports in 2017, a 60 per cent fall implies a 26 per cent decline in overall exports of mode 1 and mode 2 services. Most of the UK’s mode 3 service exports would be secure, but mode 4 services exports would be curtailed and mode 5 exports would experience a similar reduction to that of goods trade.[_]

This report does not assume any fall in services exports to the rest of the world following Britain’s exit from the single market, although a chunk of Britain’s services exports to non-European markets is driven by the hub status it has developed through its membership of the EU. This report also assumes that Britain will be no more successful in gaining access to the US and other economies’ services markets than the EU will. In reality, it would almost certainly be less successful because trade deals are about reciprocity, and the UK will have less leverage than the EU by virtue of its much smaller size.

NIESR estimates that the overall trade impact of quitting the single market and trading with the EU under WTO rules would be in the order of 6 per cent of GDP by 2030. Taking into account the impact on all modes of services exports, what percentage of this will come from the damage done to services trade? Agreeing an FTA will reduce the loss of goods trade and hence the overall hit to GDP, but will not lessen the loss of services trade and the impact this has on GDP. Using the treasury’s forecasts and those put together by the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics yields similar numbers (see table 10).

Cumulative Economic Impact by 2030

Chapter 10

Britain is a hugely successful exporter of services. Much of the overall rise in British exports over the last 20 years has been in services—the performance of manufactured exports has been easily the worst in the G7—and on current trends, services exports are likely to exceed goods exports within five years. The EU is by far the biggest market for these services, something that cannot be explained just by geographic proximity and the EU’s market size. And leaving the European Single Market will hit the UK’s services exports harder than its goods exports.

Brexiteers claim to be setting the UK free to trade more with non-European markets. According to their narrative, the EU places regulatory burdens on British exporters, but does not boost trade between the Britain and the EU; Britain can leave the EU without damaging its trade with EU member states. This fundamentally misunderstands the nature of services trade and the difficulties of gaining unimpeded access to the services markets of the US, let alone big emerging economies such as China, India or Brazil.

The big obstacle to trade in services is not tariffs but non-tariff barriers (NTBs), such as differing national regulatory standards. While some NTBs may be deliberate means of restricting imports, most arise from genuine differences in national approaches to solving public-policy problems. The EU has been determinedly, if slowly, breaking down the regulatory barriers to trade in services, through a combination of mutual recognition of member states’ rules and supranational rules in other sectors, such as financial services. Where the requirements of cross-border service providers clash with the public policy requirements of a member state, the European Court of Justice acts as the arbiter.

Liberalising services trade across the EU may be a work in progress, but it has still gone far further than anywhere else in the world. And for this reason, Britain’s services trade with the EU is likely to grow at least as fast as its trade with the rest of the world, notwithstanding sluggish growth in the EU economy. Leaving the EU will do huge damage to this trade; none of the British government’s proposed solutions is politically viable. This is not because the EU is attempting to bully Britain, but because Britain is suggesting solutions that would leave it in a more privileged position than EU members.

This leaves the unresolved Brexit dilemma: it is impossible to simultaneously oppose the existence of collective European institutions such as the European Court of Justice and the European Commission and enjoy a deep and comprehensive trade deal with the EU that addresses NTBs to services. To insist on the full sovereignty of Westminster is essentially to demand that its sovereignty takes precedence over the sovereignty of all other parliaments in a services deal. This approach can only have one outcome: a trade deal that does nothing about NTBs to the trade in services, leaving UK services firms operating according to different rules from EU member states, and trading much less with them. And the UK will pay a hefty price in terms of lost economic activity, employment and tax revenue.

Chapter 11

The appendix describes the details behind the simulated scenarios and baseline modelling assumptions. It should be read as a companion note to the simulations output. The simulations report the annual percentage point changes of the variables of interest (for example, GDP) with respect to the baseline forecast.